By Nancy Griffin

Maine’s work force must grow if Maine’s businesses are to grow. That’s the conclusion of a new report on the future of the Maine economy.

Across the state, jobs remain empty as employers seek to fill them, according to the roughly 1,000 business people interviewed and hundreds of experts who participated in the report. A similar report published eight years ago, when the economy was less vigorous, concluded the biggest obstacle to Maine’s economic growth was the high cost of doing business here—including taxes, health insurance, energy, and regulations. Now business is booming and things have changed.

At the growing Front Street Shipyard in Belfast, Human Resources Director Penny Combs attests to the report’s findings.

“We’re having the same problems as everyone else,” she said. “I go to job fairs and high schools to see who’s looking for jobs. I archive every resume we get. I work with three or four community colleges and boat-building schools, one out of state. I’m doing what everyone else does.”

Combs said five years ago, multiple applications came daily.

“Now we’re lucky to get one once a week. I spend a lot of time at high schools trying to convince kids they can get a shorter, less expensive education leading to a good job,” she added.

The report, “Making Maine Work: Critical Investments for the Maine Economy,” highlights several other challenges and suggestions for meeting them, including the implementation of high-speed broadband throughout the state. Produced by the Maine State Chamber of Commerce, the Maine Development Foundation, and Educate Maine, the report offers suggestions for the next governorto remedy the situation.

Despite a small increase in population in Southern Maine, where the demand for workers is unsurprisingly higher, even the influx of 1,704 people between 2010 and 2017 won’t provide the labor needed for available jobs. Cumberland County alone, where 40 percent of Maine’s job growth is happening, would need an influx of 6,000 workers before 2034 to meet the potential growth.

Fourteen counties lost 2,697 people in the same eight-year period through a combination of more deaths than births, and virtually no in-migration.

The report, published in July, states: “From March 2013 to March 2018, Maine added 25,000 new jobs, yet its workforce was unchanged. The Maine Department of Labor reports that unemployment has reached decades-low levels in recent months, and stood at 2.8 percent in May 2018. Continued job growth in this situation is unsustainable.”

A key recommendation is to grow the work force by marketing Maine not just as a vacation destination, but as a career destination. The plan also calls for providing college education and debt-forgiveness incentives, and attracting and helping integrate foreign immigrants.

The report does not address seasonal industries such as farms, hotels, and restaurants which have come to depend at least partly on temporary foreign workers. Many businesses were unable to get enough foreign workers due to visa constraints. But the report’s findings about a smaller local work force, added to the visa limits, meant some seasonal restaurants failed to open or were forced to close. All along the coast, restaurants were advertising from spring into summer for every kind of worker.

“We opened a new restaurant in Scarborough in July and it was crazy, trying to find cooks,” said Jen Brenerman. She and her husband, Brian, own and operate downtown Portland’s Shays Grill Pub and their new venture, the 100-seat Dunstan Tap and Table. “Our regular four or five cooks were working long, long hours while new cooks came and left, usually without notice. This week, we’re fully staffed. I hope it lasts.”

Jen and Brian have been in the restaurant business for a combined 50 years, and she reports her friends in Portland restaurants are having the same problem. Some have cut back on hours, others on seating, to try to accommodate staffing shortages.

“We were forced to shut down between 2 p.m. and 5 p.m. because our short staff didn’t have time to prep. Customers don’t understand, so you get bashed on social media when you have to close. It’s not easy.”

Other recommendations include education goals, such as helping already employed adults gain new skills; doing more to help young students achieve in school; encouraging diverse educational pathways; and increasing funding for education.

Affordable high-speed broadband is the third report recommendation. The authors urge the state to commit to a $100 million annual program for broadband expansion, private and federal investment in the state broadband program, and finding ways to increase digital literacy for residents.

The fourth group of recommendations are aimed at one of the primary obstacles identified in the first report—the cost of health care in Maine. While it is not the top challenge identified this year, it is the first concern participants feel the next governor should address by implementing expanded Medicaid as voters chose in last year’s referendum. They say the next two priorities for a new administration should be increasing the work force and high-speed internet.

About half of Maine’s roadways, 17,600 miles, are not served by adequate broadband and “what is considered adequate today won’t be adequate five years from now,” said the authors.

The last goal encourages development of a comprehensive state economic strategy in 2019. Energy costs, transportation needs, and increased research and development are the next three most important issues, they found.

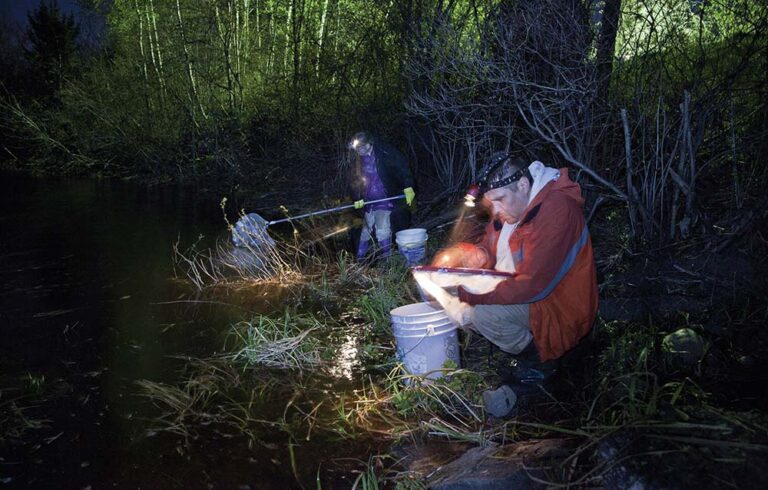

Maine’s advantages for incoming workers include natural beauty and outdoor activities, the authors point out. Competitive advantages for businesses include natural resources that can be used to develop alternative energy sources, seaports, thriving food, aquaculture, and forest products industries as well as innovative research centers.