A much-used statistic says the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 98 percent of the world’s oceans.

While one might imagine the warming is due to a “Bunsen burner-like” effect in the gulf itself, it actually results from two sources of water that feed the gulf.

The effect is like those old sinks that have separate hot-water and cold-water dials, said Carla Guenther, chief scientist with the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries in Stonington.

“We have conditions drawing from the hot-water tap more than the cold-water tap,” she said. On Aug. 26, Guenther gave a virtual presentation, hosted by Deer Isle’s Chase Emerson Memorial Library, on climate change in the gulf.

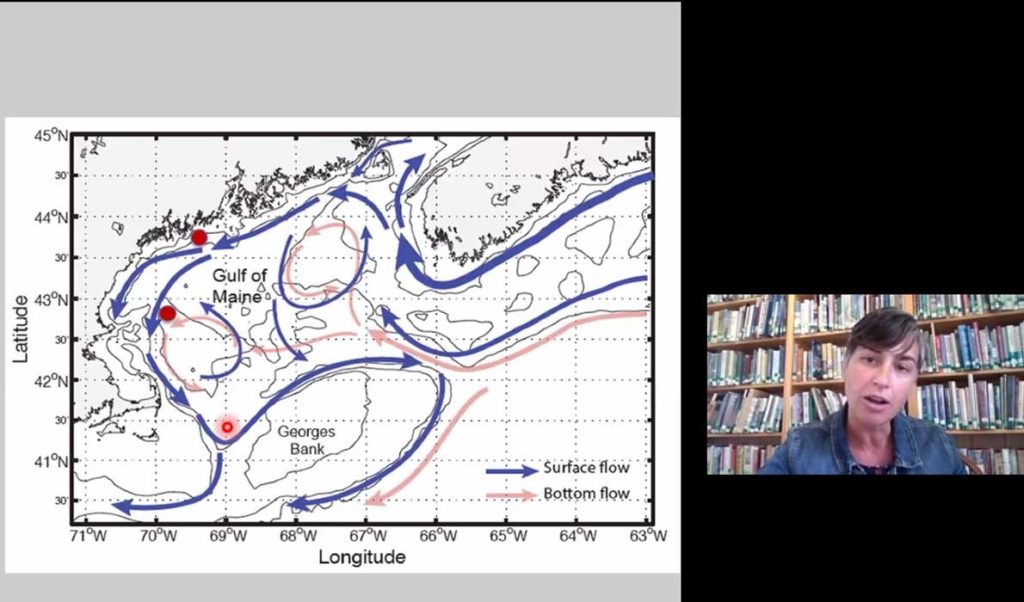

Guenther explained that the Labrador Current, driven by a large atmospheric pressure system over Canada, brings cold water to the gulf. Through patterns of circulation that span the Atlantic Ocean, the warmer waters of the Gulf Stream also get mixed into the gulf.

But patterns of warming air and water are causing the Gulf Stream to become less consistent over the past decade, she said.

In 2011, for example, two major hurricanes drove the Gulf Stream’s warmer waters off southern New England north into the Gulf of Maine. That resulted in an overall temperature increase that year of about 8 degrees centigrade. Although the Gulf Stream has retreated somewhat since then, scientists are now seeing an increase in the number of warm “core rings” spinning off from it, and the duration of the warm rings of water is longer.

“That’s contributed to the Gulf of Maine being warmer overall,” she said.

A feedback loop is also causing the Gulf Stream to slow, which further impacts temperature distribution, she said.

The result? The latest ecosystem report from the Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Mass., says the gulf is seeing proportionately more hot water than cold water over the last five years, she said.

“It’s not that we have a burner on in the gulf. It’s that the sources of water are changing,” she said.

Warming waters are having different effects on different species. One of Maine’s iconic resources, lobster, enjoys warm water and the results can be seen in increased landings over time. Lobster stocks grew three-fold in 20 years while landings grew five-fold.

But another iconic species, shrimp, has essentially collapsed with warming waters and has been closed since 2012.

Why has the story been so different for the two?

The answer behind lobster is partly due to the disappearance, due to overfishing, of Atlantic cod, a primary predator, she said. At the same time, lobster larvae enjoy a certain amount of warmth. Maine is at the northern end of the Atlantic lobster’s range. But the warming gulf has expanded the amount of sea bottom where larvae, which have a specific thermal threshold, can settle down and grow unhampered by predation.

Conversely, Maine is at the southern range of Northern pink shrimp, which enjoys cold water and typically arrived off Maine in the winter.

Recent surveys show there are far fewer shrimp in the gulf today than a decade ago.

“The shrimp fishery doesn’t seem to be coming back anytime soon,” she said.