The happenstance discovery of a gravestone in her hometown of Brewster, Mass., led Dr. Meadow Dibble to launch a public history initiative devoted to researching and reckoning with New England’s role in the slave trade.

In a recent Maine Conservation Voters “lunch and learn” series online, Dibble recounted growing up in the town on Cape Cod Bay, and then returning there and learning about her hometown’s participation in the transatlantic slave trade.

Brewster had long been dedicated to seafaring, with residents working as fishermen and whalers. Today, locals not only honor that seafaring heritage, but they have dedicated resources to archiving the tradition’s stories, which have been told for generations.

Dibble’s childhood memories of this place include images of her father working as the storekeeper at the Brewster General Store. In school, she learned about the Civil War, and New England as a sanctuary of abolitionism.

“We who hail from New England were brought up believing that this region was a bastion of democratic ideals, a hotbed of abolitionism. And of course, much of that is true,” Dibble said. “These are the stories we tell, but they’re very selective.”

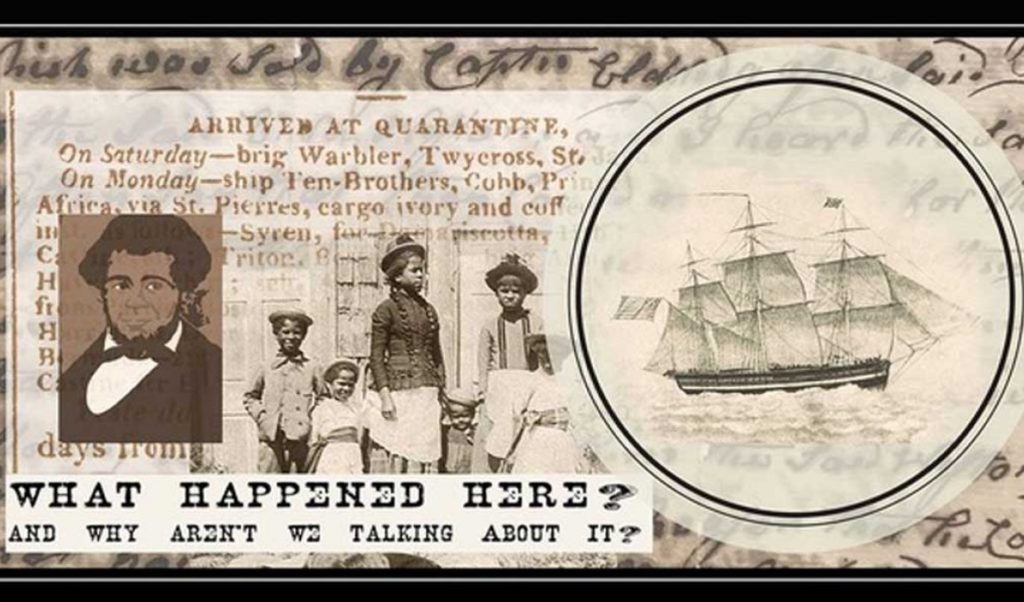

A few years ago, on a walk through a cemetery with her daughters in her cherished hometown, she stumbled upon a headstone unlike any she had seen before: “Benjamin Crosby Died in Africa 1795” were the words engraved. Why had this young man from Brewster sailed to Africa?

She visited the library and consulted the local librarian, but found no information about Cape Cod’s involvement in the slave trade. With no answers, she headed back to the cemetery. Several more names of those who had died in Africa appeared on gravestones. What’s more, there were several more headstones of men who died in the West Indies and Cuba during the 19th century. These graves were of fishermen and whalers, so why were these men going to the Caribbean?

“Of course, if you bother to ask yourself what was in fact happening in the Caribbean over the course of three centuries, then if you’re a rational individual, whether you have a PhD or a GRE, you can start to put two and two together,” she said. “It’s something we don’t talk about it.”

British colonists had established a trade route that enabled sugar to be imported from the British West Indies to the northern colonies. The Caribbean islands became sole producers of the commodity, while New England produced food and tools for the sugar production, allowing the Northeast’s economic ascent during the 18th and 19th centuries.

And if that were not enough to disqualify New Englanders claiming the moral high ground, Dibble suggested more complicity was likely.

“If Cape Codders clearly had no moral qualms about supplying those West Indian plantations with the salted herring that would feed the enslaved African laborers of the Caribbean,” she asked, “or the grains that they would consume, or the hardware that they would use to till the fields, or the livestock that would run the plantations, how likely is it that Cape Coders or New Englanders drew the line at importing slaves?”

Would these seafaring Cape Codders, she asked, have left the highly profitable commerce to their neighbors in Rhode Island or in Maine, on moral grounds?

Dibble discovered that routine slaving voyages had been orchestrated by Boston merchants, and from ports in Newburyport, Gloucester, Salem, Bristol, Newport, New Bedford, as well as in Portsmouth, N.H., and Mystic, Conn., and New York.

And slave trading also was based in Maine coastal ports, including Brunswick, Bath, and Portland.

In fact, there was complicity along the entire East Coast.

“Northerners had essentially cornered the market,” Dibble said.

As she dug for the truth, Dibble found documentation of evidence of slave trading in New England, but none specifically linked to Cape Cod.

In 1788, Massachusetts banned slavery, but it wasn’t until 1808 that a federal ban was enacted on slave trading. However, it persisted, and with no impedance on this lucrative barbarity, the commerce continued through the Civil War. Those active in the slave trade were guilty of concealing evidence, throwing their account books overboard, she said.

“It would seem that one of the challenges that we face today is that we have developed the habit as a society, as a region, of turning away from [this] evidence, a sort of willful amnesia set in over the years,” she asserted.

The evidence catapulted her toward a mission to not only discover what happened, but to uncover why had she not known about this immense foundation of New England history.

“If you don’t know your history, it’ll repeat itself. We are living this right now. What we don’t know about our history hurts others,” Dibble said, referencing the Black Lives Matter movement.

In response to her discoveries about New England’s often-overlooked ties to slavery, Dibble has created the Atlantic Black Box Project, what she calls a public history inquiry that relies on an “enlightened crowdsourcing” model. Its aim is to empower interested community members—whether high school students or retired senior citizens or anyone in between—to conduct research into the maritime history of New England and to share their findings with others thanks to an online database, or “black box.”

Today, only what she calls a biased archive remains. That ignorance, or maybe even denial, left Dibble with a moral obligation to continue the search through history.

For more information, see atlanticblackbox.com