On the night of Oct. 10, 1905, John Taylor, captain of the Blanche King sailing off North Carolina’s Cape Fear, observed something that raised his concern.

Taylor saw “a four-masted schooner, sailing erratically outside the usual shipping channel, with her red light hanging from its rigging.”

What Taylor soon discovered aboard that wayward schooner was the grisly scene of one of the worst maritime mutinies and murders ever recorded.

The tale of the four-masted schooner Harry A. Berwind, and its captain, Edwin Rumill of Pretty Marsh on Mount Desert Island, was recounted by Tim Garrity for an April 13 installment of Chebacco Chats, a lecture series hosted by the Mount Desert Island Historical Society. Garrity was executive director of the organization 2010-2020, and wrote about Rumill and the Berwind for the maritime edition of the organization’s publication Chebacco.

The Berwind’s taffrail, a device that records a sailing vessel’s distance traveled, is among the historical society’s artifacts, and it triggered Garrity’s interest in what turned out to be a shocking and illustrative bit of history

“It’s sort of like an odometer for a sailing vessel,” Garrity said of the item. “It hangs off the back of the boat and drags through the water.”

A note attached to the taffrail indicated it was owned by Capt. Edwin Rumill “and that he died in a mutiny in 1905.” Garrity was intrigued and began to investigate, but was suspicious of the substance of the note.

“I had my antennae up for this, that maybe this was not quite true,” he said. But upon digging he found documentation, including a biography of Rumill by Jaylene Roth, and the story was every bit as dramatic as the note suggested.

The mutiny, which resulted in the murder of the ship’s four officers, including Capt. Rumill, and one of its black sailors, is best understood in the context of the era and the maritime world, Garrity explained.

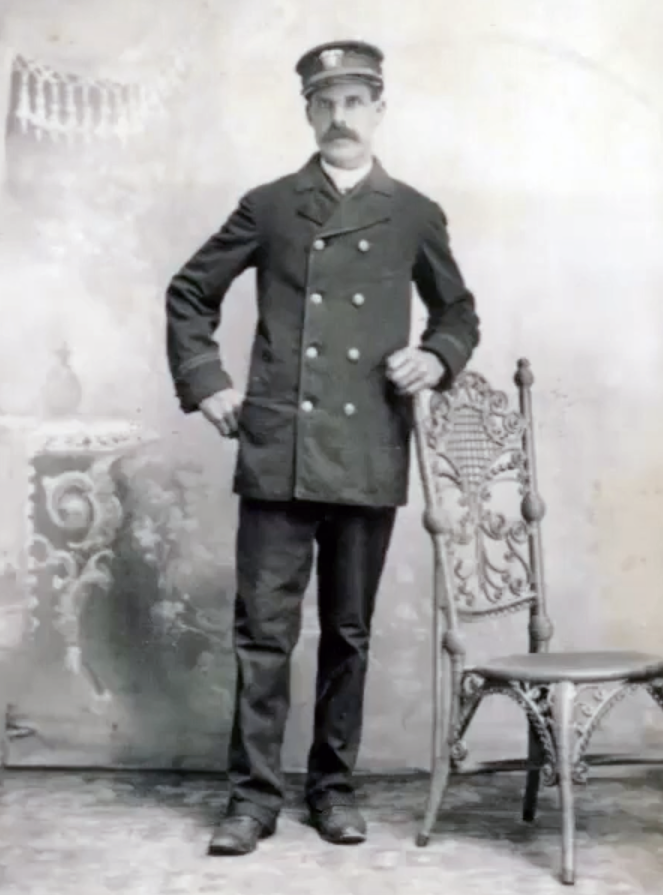

Rumill had been a mariner for some 30 years, sailing the globe and returning infrequently to Pretty Marsh. His granddaughters, who live on MDI, estimated that he spent a total of about 75 days on the island during his maritime career.

“He was very ‘salty,’” Garrity said, and was aboard several ships that wrecked. He served on one-, two-, three-masted ships and a steamer before captaining the four-masted Berwind.

“We often have a romanticized view of the days of sail,” Garrity said, “the great ships that traveled around the world. There is a reality that is revealed in this story that life at sea was really hard and violent. The conditions that sailors worked under were absolutely brutal.”

A government study published in 1874 concluded that “life at sea is worse than any prison,” Garrity found.

“It was also a place where African-American sailors could find an alternative that was marginally better than a life of enslavement or working in the Jim Crow South,” he added.

Black sailors were common, and for mariners from New England and Maine, encountering them for the first time was often surprising.

MDI native Augustus Savage in 1854 wrote to his wife that while taking a merchant ship to Jacksonville, Fla., “I have not seen anything but Negroes since I have been here.” While serving aboard a ship during the Civil War, Savage wrote that half the crew were black.

But despite their prevalence, black crew were segregated aboard ship. And officers had well-established power over their crews. Rumill wrote about a conflict with a ship’s cook in which he choked the man, leading to him suspecting the cook was poisoning his food in retaliation.

“It was routine that harsh discipline was meted out,” Garrity said.

On that fateful journey, the Berwind sailed from Philadelphia in July with a load of coal to Cuba, and returned to Alabama where lumber was loaded aboard. Though it was a 200-foot long vessel, the ship had just four white officers and four black crew members.

“There was a great deal of racial strife aboard the ship,” Garrity said, including an exchange between a crew member and an officer in which the phrases “black son of a bitch” and “white son of a bitch” were used.

The heat of the southern regions exacerbated tensions, along with the challenging work “and abysmal food,” he said.

“Serving bad coffee was said to be the match that lit the bomb of the uprising on board the Berwind,” according to reports at the time.

Off Cape Fear, Capt. Taylor recognized the Berwind because its captain Rumill was a friend. As Taylor’s ship approached, men aboard shouted, “For God’s sake, come to our assistance, we’ve got a man here who has killed the captain, the mate, the engineer, and a steward, and just now a sailor!”

Taylor, upon boarding, found two black sailors had bound another. Puddles of blood revealed where the others had been murdered, and he learned that two of the officers may have been alive but wounded when they were thrown overboard. The ship was leaking and a part of a mast was broken.

The three black men—Robert Sawyer, Arthur Adams, and the bound Henry Scott—were suspected of working together.

“This was immediately interpreted as a race mutiny,” Garrity said, an uprising of the blacks against the whites, even though Sawyer and Adams reported apprehending Scott and that a fellow black sailor had been killed in the struggle to stop the violence.

The Ellsworth American headline read: “Murdered on the High Seas by Mutinous Negroes!”

The three were brought ashore in Wilmington, N.C.—where a lynching had occurred just weeks earlier—and tried for mutiny and murder. Sawyer and Adams, though they had apprehended Scott, were convicted and sentenced to hang. Scott faced the same fate, but when a minister visited with him shortly before his execution, Scott exonerated the others. He also reported that Rumill had withheld food and water from the crew.

President Theodore Roosevelt commuted Sawyer and Adams’ sentences to life in prison. But the story didn’t end there. Their plight came to the attention of stage and silent film actor H.B. Warner, “the Tom Hanks of his time,” as Garrity described him. Warner and attorney Joseph Buhler worked to free the men, and President William Howard Taft finally commuted the sentences to time served.

After being freed, Sawyer was hired by Warner as his personal assistant and Adams was hired by Buhler for similar work. Garrity played a clip from the 1946 film It’s A Wonderful Life featuring Warner late in his career playing Mr. Gower, the pharmacist for whom the James Stewart character worked.

Capt. Rumill’s son George was an early aviation hero of World War I and also flew in World War II and his daughter Edna became a drama teacher. Edna’s daughters still live on MDI.

Garrity left the audience with a question: Why has the mutiny and murder been relegated to a footnote in Maine maritime history?

To view Garrity’s presentation and learn about other Chebacco Chats, see: mdihistory.org.