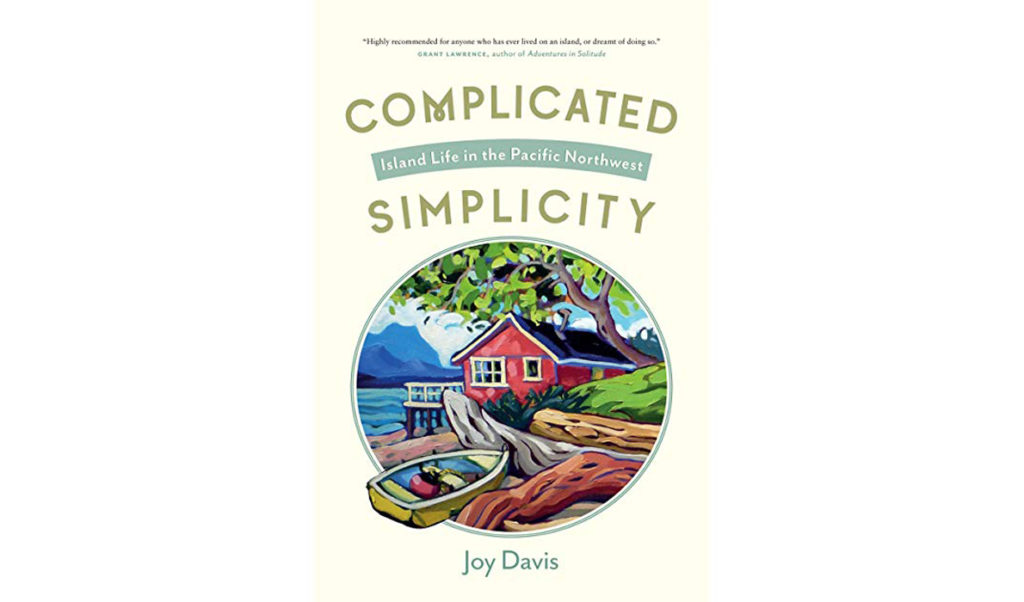

Complicated Simplicity: Island Life in the Pacific Northwest

By Joy Davis (2019)

Review by Tina Cohen

Author Joy Davis, who directed the museum and heritage programs at the University of Victoria, has written a book jam-packed with useful things to consider if exploring a move to an island residence. It’s a compendium of how-to and what-not-to for those envisioning spending a substantial amount of time in a relatively self-sufficient circumstance, living in a place surrounded by water not accessed by bridges or ferry service.

Davis and her sister spent years growing up doing exactly that off the coast of British Columbia. As well as sharing their family story, she also includes others’ experiences.

I appreciated Davis’ approach—she has expertise on the subject but recognizes each person will have their own unique relationship with the island they fall in love with. Among the characteristics that contribute to a rewarding life on island, she says a prerequisite is a deep love of the place and the experiences it offers: “This love will sustain you when things get complicated. It will make the effort worthwhile and ensure you treat the island with the respect it deserves.”

She adds, “You also need a realistic sense of what is involved in living on-island and a range of characteristics and abilities that ensure the reality becomes even better than the romantic vision.”

Those qualities include tenacity, flexibility, and resilience, as well as having logistical and practical skills, a sense of humor, discipline, and a work ethic, optimism and enthusiasm, financial resources and good health, and the ability to ask for help as well as the willingness to offer yours.

Davis focuses primarily on islands that are small, might be privately owned, may be settled with only one residence, and don’t have amenities including services or provisions. Means of transportation, typically by private boats, and of communication are essential.

Many families written about here have busy schedules with children attending schools often at some distance and adults working mainland jobs. More locally, there can be social opportunities such as book clubs, sleep-overs for kids, and exchanges of help with various projects.

There are always ongoing tasks like boat and building maintenance, securing firewood, tending animals, raising and foraging food, and accessing potable water. Davis’ own recollection is not of a life of deprivation, endless hard work, or lonely isolation. Looking back, she says daily challenges included “balancing solitude and social activities, and harmonizing simplicity and complication.”

The book focuses on a lot of “brass tacks,” and anecdotes of her own and others share hard-earned advice such as choice of a site, house design, sourcing of building materials, energy options, boat access, and weather concerns.

I may feel some occasional pinches from island life on Vinalhaven—what ferry I can get on creates the most anxiety—but I came to feel absolutely humbled by the accounts in this book. I only wish Davis had included a more detailed map showing the islands she referred to off Seattle and Vancouver, and some photographs would have been nice. She is sensitive in sharing names and places, which could have deterred her from providing more identifying information. (One can assume many who end up in solitude on islands like their privacy.) The contributors (including a few from Maine and Nova Scotia) have generously offered up personal experiences- their successes and failures, disappointments and happy surprise—to benefit others. If you or anyone you know is contemplating life on an island, this book—both cautionary and inspiring- is essential.