By Nancy Griffin

Hunting whales, a practice now roundly condemned by most of the world, once was an important part of New England’s economy in many places—especially so on Nantucket Island off Cape Cod in Massachusetts.

Whaling also was a romantic notion for many young boys who yearned for the adventure of running away to sea. But there was little romance once they were aboard ship.

Renny Stackpole of Thomaston, Nantucket native and maritime historian, spoke on the “highly specialized” nature of Nantucket’s whaling industry in a talk entitled “Adventures of a Nantucket Whaler” to residents of Quarry Hill retirement community in Camden on May 15.

“It was the dream of every boy in Nantucket” in the 1800s, said Stackpole. “First they would ask their parents for permission. If the parents said the boys weren’t ready, they’d stow away. Then they wouldn’t see home for three to five years,” he said.

“Often, when the boys left at age 13 or 15, the parents wouldn’t recognize them when they returned home,” he said.

Stackpole centered his talk on Obed Folger, a Nantucket boy who worked on the 1820s whaling ship Lady Adams, illustrating his presentation with paintings and artifacts from the whaling era.

“It was a status thing for the boys to go whaling,” Stackpole said. “But there was no end of work and nothing romantic about it. They’d be up standing on ‘hoops’ on the masts looking for whales, or they’d be endlessly cleaning. If a ‘green hand’ survived the voyage, he’d be lucky to get a one-50th share—the value price of one out of 50 barrels of oil,” he said.

“It could be worse. They might only get one-700th” depending on their prowess or the price the voyage brought in, said Stackpole. “The captain got a princely sum, because he was also an investor.”

In the 1830s, up to eight whaling ships sailed out of Nantucket. As the population of whales dwindled, ships that had sought the leviathans in the Pacific by rounding Cape Horn, or the seas past South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, were pushed to sail to the “Japan Grounds.”

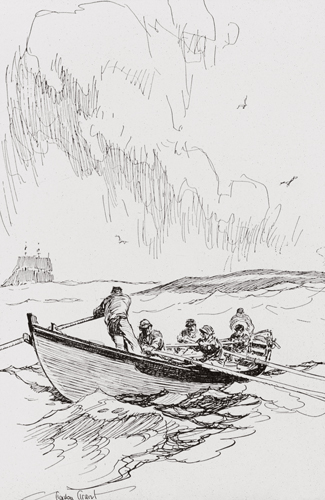

“Primarily, I wanted to give everyone a visual image of whaling,” Stackpole explained, after the talk. He displayed a small replica of a 29-foot open whale boat.

“Primarily, I wanted to give everyone a visual image of whaling,” Stackpole explained, after the talk. He displayed a small replica of a 29-foot open whale boat.

“The oars were different lengths depending on where the rower was sitting in the boat,” with the longest oars 18 feet long, used for steering.

He also showed the audience an authentic “toggle harpoon” from the mid-19th century. The weapon’s pointed end swiveled once it penetrated the whale’s body so it could not easily be pulled out.

“Whaling required intensive skills—chasing, harpooning and killing the whale—and the skill to bring the body safely alongside the ship with the flukes to the bow and head to the stern. then to ‘try out,’ or reduce the whale blubber into oil.’

The best, purest oil was found in the forehead or “case” of the sperm or bottlenose whale.

“The third pressing of this highly-prized ‘spermaceti’ was used primarily for smokeless, odorless ‘sperm’ candles,” Stackpole said.

By the 1830s, a sandbar was growing across Nantucket Harbor, so that finally, even the ingenious system of a floating dock, placing pontoons around the ships and pumping water to get them into the harbor, became too impractical and time-consuming. The industry moved to mainland New Bedford.

Whaling focused worldwide attention on Nantucket, and when the whaling fleet moved on, tourism quickly moved in, and as seems inevitable with such places, “Now it’s for the wealthy,” he said.

In the whaling days, everyone on the island was involved in some fashion with the trade, “either making barrels or provisioning ships for the voyage.” Green hands would often be sick for the first three weeks. Their captains might not decide whether to go to Cape Horn or Good Hope until they stopped for provisions in the Azores.

In the Galapagos Islands, there was a cask in a tree in a cove nicknamed “Post Office Bay” where crews could leave or pick up mail. If a ship headed for the grounds met another going home, they would exchange letters.

Stackpole read two letters in his talk. In one letter, a wife asked her husband: “What did you do with the hammer?” His reply, months later, was: “What did you want with the hammer?”

Stackpole has, among other things, served as director of the Penobscot Marine Museum and curator of The Whaling Museum in Nantucket. He has also written several books including his recent titles, Sea Letters and Treasures in the Attic.