John Bird speaks at the Farnsworth Art Museum. PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN

By Tom Groening

Today, Rockland is a lively, commercially diverse service center. In summer, tourism dominates the downtown, thanks to the Farnsworth Art Museum, galleries, schooners, and several fine restaurants and coffee shops. The city also boasts a large working waterfront, with a marina and boat service yard, a U.S. Coast Guard base, and a ferry terminal.

But it was industry that has been Rockland’s raison d’etré, and even today, it has about 1,000 manufacturing jobs, putting it third in the state, per capita.

The city’s story has been told most recently by John Bird, a Rockland native whose career in private education administration took him south along the East Coast, to the Midwest and Southwest. When a career change beckoned, he and his wife happily returned to the Midcoast in 1990.

Bird’s Rockland, Maine: Rise and Renewal, a generously and richly illustrated narrative history, promises to be an engaging read, despite its size. As Bird jokingly explained in a presentation at the Farnsworth on Jan. 23, “I’m getting critiques about the tome-like size of the book,” which weighs-in at more than seven pounds and includes more than 500 pages.

In his talk, Bird recounted the early days of European settlement. Among the first families in the 1760s were the Tolmans, Reeds, Lindseys, Crocketts, Jamesons, Spears, Rankins, and Blackingtons, and some bearing those names live in the area today.

Rockland was once part of neighboring Thomaston, Bird explained, and in fact was not incorporated as its own municipality until the relatively late date of 1854. But by 1850, its population of 5,000 was double that of Thomaston.

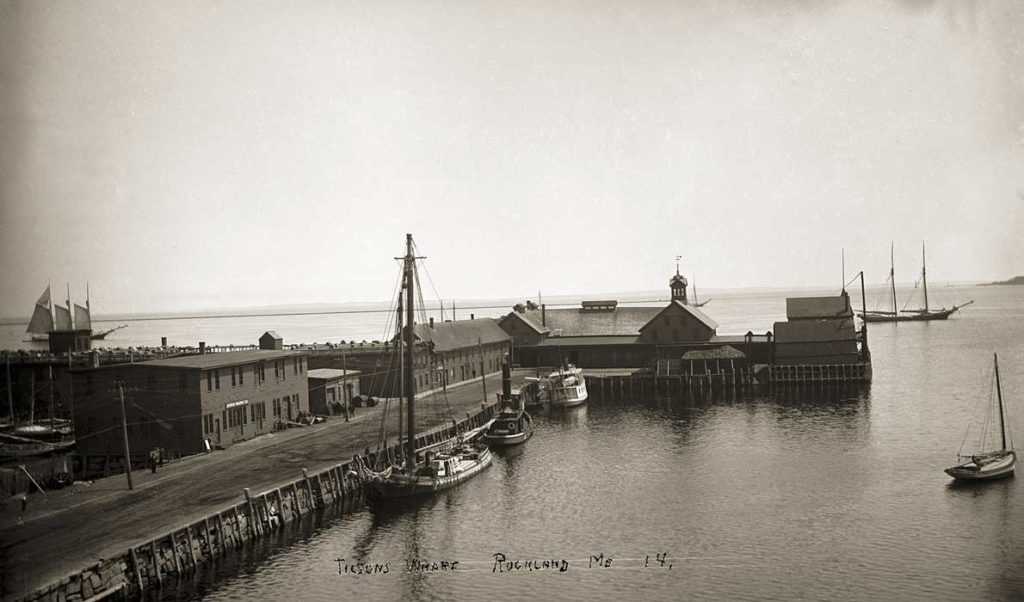

At that time, the peninsula now bounded by Main Street, Park Street, and Tilson Avenue—mostly built on fill—was punctuated by piers and covered with lime kilns, shipyards, and manufacturing plants.

By 1910, other elements had been added. Steamships were landing at the South End, linking the Midcoast to Boston. An Andrew Carnegie-funded library had been built. And the Samoset Hotel had opened on the northern edge of the city.

W.H. Glover, whom Bird described as “the master builder of Rockland,” was the contractor for the Samoset (it burned in the 1970s). He also built the Rockland Breakwater Lighthouse, the McLain School, and the court house, which Bird called “perhaps our most distinguished building.”

Glover also built about half of the shingle-style “cottages” on Islesboro.

But resource extraction continued to define Rockland for much of the 20th century, most notably, the processing of lime. The stone was quarried in the area, shipped to the harbor where it was cooked in kilns, and then sent to ports along the East Coast for use in mortar and plaster. The last kiln closed in 1958.

David Hoch, the last president of the Rockport and Rockland Lime Co., verified the city’s claim to having the deepest lime quarry in the world with classic Maine understatement: “It’s deep enough.”

Notable women in Rockland’s story include Jessie Dermott, born to a sea captain in the city, who later earned fame as an actor on stage and screen as Maxine Elliott. Elliott was one of the most photographed actors of her time. She became the first woman to establish, own, and operate a theater just off Broadway in New York.

Another stand-out, also in the arts, was Louise Nevelson, whom Bird called “the incomparable Louise,” a colorful character whose sculpture won her critical favor in the 1940s. Born in Russia, her family emigrated to Rockland in 1905.

A third woman Bird whom labeled perhaps the most influential in Rockland history was Lucy Farnsworth, daughter of a prominent granite business owner. She died in 1935 and in her will, Farnsworth bequeathed funds to start the museum bearing her name and which has become the centerpiece and transformative driver of the city’s current prosperity and creative economy.

But Rockland saw darker days through global changes that hurt manufacturing in the U.S. through the 1970s. One of the industries that remained was a fish-rendering plant which covered the town in an offensive smell. In a bold move, a city council in the 1980s began pressuring the large employer to clean up its act, and the plant finally closed in 1987.

Bird recalls an observation made about the downtown in those years: “You could roll a bowling ball down Main Street on a Friday night in 1985 and not hit a soul.” Not so today.

Bird cited the 2006 Brookings Institute report on Maine which urged coastal towns to “meld tradition and the creative economy. Rockland is the poster child for that,” he said. He also put the date at which the city became a tourist destination at the early 1990s.

A local booster group, Rockland: Share the Pride, marked a turning point, he said. When the group went dormant, civic leaders didn’t feel the need to revive it—which revealed that the city was now optimistic about its future.

In an earlier book, 2011’s Rockland, Maine’s Tidal Turn, Bird gathered profiles of some of the “heroes” who helped revive the city. It included chapters recounting “the birth of the blues,” when an unlikely cultural institution, the Rockland Blues Festival, was established, and another unlikely community catalyst, the Rock City coffee shop, helped push the revival.

Today, some 25 galleries and restaurants operate in the city.

“Rockland’s comeback, evident over the past three decades, has been powered by ideas, creativity, and services driven by the arts, entrepreneurialism, and tourism to a much greater extent than in the past,” Bird said. “And the community’s resurgence has been aided by an invaluable natural resource: its sublime location at the mouth of the expansive, breathtakingly beautiful Penobscot Bay.”

Bird credits the Rockland Historical Society for publishing the book, and especially Brian Harden and Ann Morris. He also thanked Jane Karker for map work, its designer Wendy Higgins, and local artists Debby Atwell and Richard Iammarino for illustrations.

For more information about Rockland, Maine: Rise and Renewal, see: http://rocklandhistorical.com/calendar/john-bird-launches-his-new-history-of-rockland/

In 1945, author Dan Stiles had this to say about Rockland in Land of Enchantment, his book profiling communities along the Maine coast:

“In most of the towns in and around Penobscot Bay the summer visitor is a personage. His wants are anticipated, his habits have been studied… all in the line of business. But in Rockland the ‘summer trade’ is only incidental. Biggest, busiest, and most important of the [Penobscot] Bay towns, Rockland has other fish to fry… Not that Rockland doesn’t welcome the tourist; it does and has always. And many tourists find it more interesting to observe and explore a working, active seaport than to absorb the charm and tradition of towns whose heyday lies many years in the past. No invidious comparisons are intended and none should be inferred, but the visitor to the Bay area does well to understand and remember that Rockland is different.

“Rockland has always been different and generally in ways that can only be described in superlatives. As this is written, in 1945, its distinction is based upon the lobster. Yesterday it was lime, tomorrow it may be something else…

“Rockland has always lived in the present and looked toward tomorrow rather than toward the past.”