By Carl Little

For a couple of months, the Portland Museum of Art is stealing some of the Farnsworth Art Museum’s Wyeth thunder. “N. C. Wyeth: New Perspectives” (through Jan. 12) offers 46 paintings and one drawing by the granddaddy who launched the family art dynasty at the turn of the last century (the work in the show dates from 1903 to 1945).

The exhibition is something of a greatest hits selection, from paintings for some of the original illustrations for Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and other classics, to an outstanding group of Maine landscapes. There are war scenes, gnomes bowling, fence builders right out of Robert Frost, and three self-portraits. Lenders include the Brandywine River Museum of Art, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, the Wyeth family, and Linda Bean.

Wyeth drew his greatest fame from illustrating—he was a celebrity artist in his time—and the PMA offers some memorable images from his repertory. Whether depicting the creepy blind Pew tapping his way down a dark lane in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island or David Balfour gripping a broken mast as he watches his brig, The Covenant, sail off in Stevenson’s Kidnapped, Wyeth was brilliant at producing the visual accompaniment to a text. Elsewhere, the fierce, bearded, gnarled-knuckled Captain Nemo from Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island would win any staring contest.

Wyeth was a master of horses. His bucking bronco cover for the Saturday Evening Post, the earliest piece in the show, is a stunning stop action image of equine flesh trying to buck its rider. Rounding Up, 1905, painted for an article in Scribner’s Magazine, recalls scenes from Lonesome Dove while Bronco Buster, 1906, uses a rodeo scene as the vehicle for an advertisement for Cream of Wheat.

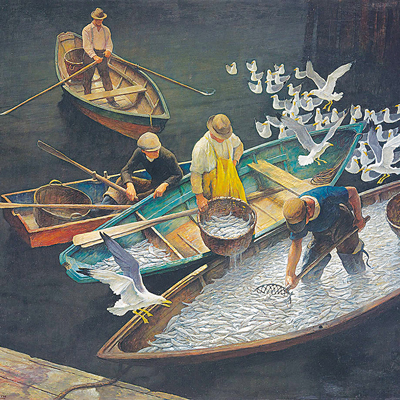

The Maine paintings include the Farnsworth’s Bright and Fair, 1936, a view of the Wyeth home “Eight Bells” in Port Clyde, The Harbor at Herring Gut, 1925, a light-filled panorama of working waterfront; Black Spruce Ledge, 1939, an homage to lobstering; and Dark Harbor Fishermen, 1943, a strangely morose image of men reaping the bounty of the sea (the painting was part of philanthropist Elizabeth Noyce’s bequest of art to Maine museums).

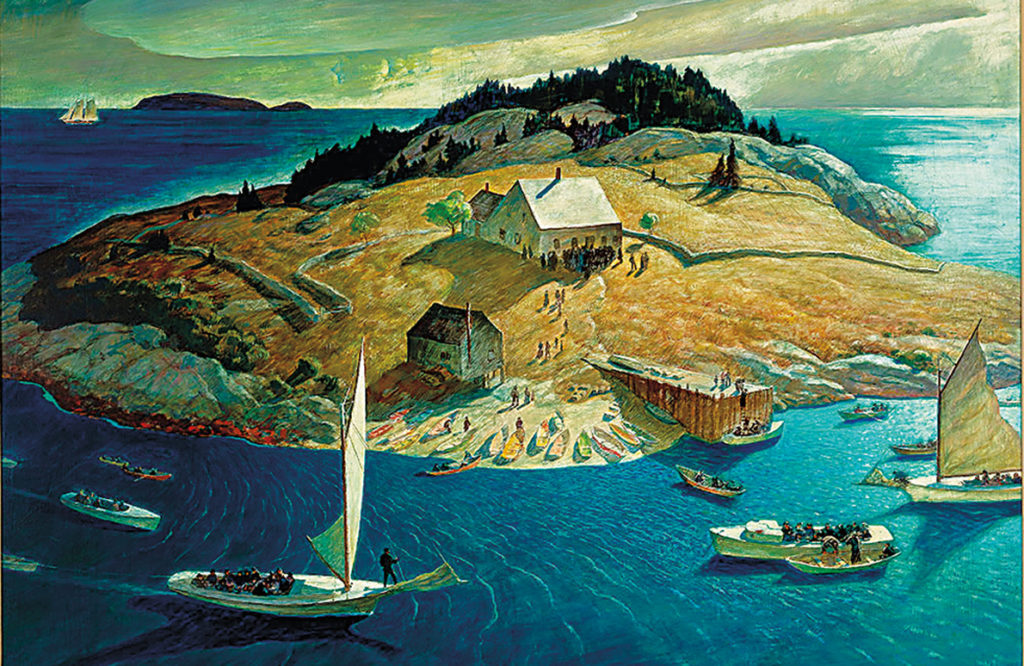

Originally meant to illustrate Kenneth Roberts’ Trending into Maine, the stunning Island Funeral, 1939, offers a bird’s-eye view of boats arriving at Teel’s Island off Port Clyde for the funeral of 96-year-old Rufus Teel. Wyeth had a relationship to the Teel family similar to his son Andrew’s to the Olsen’s. The image brings to mind the contemporary practice of honoring the death of an islander with a special flotilla.

The “new perspectives” part of the show’s title refers to commentary offered by seven individuals invited by the PMA to respond to particular paintings in the show in order to expand the “exhibition narrative.” In many cases, the comments, posted alongside the paintings, undercut the image, especially Wyeth’s portrayals of Native Americans.

Rachel Allen, a member of the Nez Perce tribe and assistant curator at the Peabody Essex Museum, speaks to the damage done by the broad dissemination of a romanticized rendering like Wyeth’s On the October Trail (A Navajo Family), 1907. “Each time an image is repeated,” she notes, “it gains more authority…more credibility” until it becomes the standard for representing a people.

In his take on Wyeth’s endpapers for an edition of James Fennimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, 1919, African-American artist and illustrator Daniel Minter remarks on the imbalance present in the scene of a white man standing in a canoe framed by two “subservient Native Americans.” The painting “is about taming and conquering,” he observes. “It’s even nostalgic in that way.”

No doubt some Wyeth fans will take umbrage at these retrospective critiques. In my view, as Maine prepares to celebrate its bicentennial, these “new perspectives” help counter-balance what has been largely 200 years of white rule and move us toward setting the cultural and art-historical record straight.