By Nancy Griffin

It took years of painstaking effort to restore seagoing puffins to a Maine island where they had historically nested but had long ago disappeared, victims of human hunting for their meat and feathers.

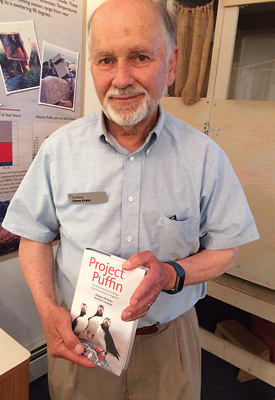

Now, the results of those years of effort that began in 1973 have reached a milestone. Project Puffin recently received its best news yet, said founder Dr. Stephen Kress: a record number of nesting pairs on Eastern Egg Rock. This year’s count is 188 nesting pairs, up from 175 pairs in 2018.

“It’s a small colony on the southern edge of the resource, but it’s important,” said Kress, National Audubon Society’s vice president for bird conservation, director of the Audubon Seabird Restoration Program and Hog Island Audubon Camp, and an instructor with the Cornell Lab Bird Academy. Kress is retiring from his several posts this year.

When Kress founded the Puffin Project, researchers weren’t sure how to lure the birds back to stay on Eastern Egg Rock, a seven-acre island six miles off the coast of Pemaquid Point.

Puffins usually spend many months of the year at sea and are capable of spending years at sea without touching land. Kress is co-author, with Derrick Z. Jackson, of Project Puffin: The Improbable Quest to Bring a Beloved Sea Bird Back to Egg Rock (Yale University Press, 2015).

The little black and white birds with the large, colorful beaks are members of the auk family. Beloved for their quirky looks, the birds have been dubbed “clown of the sea” and “sea parrot.”

Weighing in at just over one pound and measuring just under 10 inches long with bright orange webbed feet, puffins can flap their little wings up to 400 times a minute, fly at nearly 55 mph, and dive to a depth of 200 feet to catch fish. They have a strong tongue that allows them to hold small fish against the roof of their mouth while they drop their lower beak to catch more, routinely between 10 and 60 small fish at a time.

“We don’t really know where they go when they leave for winter,” said Kress. “But they live long lives—the oldest known puffin is 34 years old—and they’re mostly monogamous. We do see a few divorces, but fewer of those in small colonies.”

They return to land only to reproduce. Breeding pairs produce only one chick per year, making restoration efforts slow. Researchers also don’t know what puffins do for the years before they decide to return to the island of their birth and begin the mating process.

Kress, a lifelong naturalist, became passionate about restoring seabirds—especially puffins—to their old habitats when he started as ornithology instructor at Audubon’s Hog Island Camp in Bremen in 1969.

“People were the reason they were gone,” Kress explained. “If people wiped them out, people could restore them.” The trait his seventh-grade science teacher called his “stick-to-it-ism” served him well as he began to try to achieve something that had never been done—restoring birds to an island where human activities had eradicated them.

A NEW THREAT

Now the biggest threat to the birds is climate change.

Although initially discouraged by both U.S. and Canadian wildlife officials, Kress finally won permission to begin his program, using puffin eggs acquired from Great Island in Witless Bay, Newfoundland, home to one of North America’s largest puffin colonies.

Atlantic Puffins range throughout the North Atlantic Ocean, with the largest colony in Iceland. Estimates of the world population range from 3 million to 4 million pairs. The Gulf of Maine’s largest colony, between 5,000 and 6,000 pairs, is located on Machias Seal Island, site of an old dispute over ownership between the U.S. and Canada. Colonies on undisputed Maine islands including Matinicus Rock number around 1,300 pairs.

As Project Puffin progressed, researchers hatched eggs in incubators, built burrows for the chicks, fed them vitamins stuffed into tiny fishes, and built decoys to attract the birds back to the island. This first puffin returned in 1977 and four years later, birds began nesting there.

While the puffin restoration is a success story, and the threat from humans perhaps removed, the small birds are still vulnerable to climate change, explained Kress.

“The climate threatens to undo the work with the warming waters’ effect on forage fish,” Kress said at a recent talk held at the Project Puffin Audubon Center in Rockland. “Recent changes since 2005 clearly point to the Gulf of Maine warming. Since Eastern Egg Rock puffins are at the southern end of the range, they are particularly threatened by this,” he said.

“It’s important for them to have the opportunity to adapt to this. Puffins are very adaptable. They will eat any marine fish, but we must make sure our fisheries policies leave enough fish in the sea for marine birds as well as humans.”

This year, the Gulf of Maine has been a little cooler and the colony is thriving as a result, but good years have been alternating with bad years, Kress said. “We’re very much in a system of a roller coaster as far as the puffins go. We need to be more responsible with fisheries management, and sea birds should be considered.”

Kress is encouraged by this year’s first mention of seabirds in the federal state of the ecosystem report.

“We wouldn’t have started Project Puffin if we didn’t think it was possible for the long-term survival of the birds.”