When most of us think of mapmakers, we think of the big names in mapmaking: Google, Garmin/DeLorme, Rand McNally. These are companies engaging in cutting edge technologies to push cartography into the future. But there are lesser-known mapmakers contributing to the field right here in Maine, and their work spans the spectrum of map creation.

OLD-SCHOOLING IT

Jane Crosen never set out to be a mapmaker, but when the now-62-year-old from Penobscot got her first taste of maps while working as an editor and girl Friday at DeLorme in the early 1980s, she was hooked.

Whenever her editorial duties slowed down, she volunteered to work on DeLorme’s big project at the time—a from-scratch atlas of Maine called the Maine Atlas & Gazetteer and now known to all Mainers simply as the Gazetteer.

She learned a lot about making maps working alongside DeLorme’s cartographers and artists so that when she left the company, she found her illustrative mapmaking skills in demand. She started doing map illustrations for a variety of publishers, including WoodenBoat magazine, and other clients, such as multiple chambers of commerce.

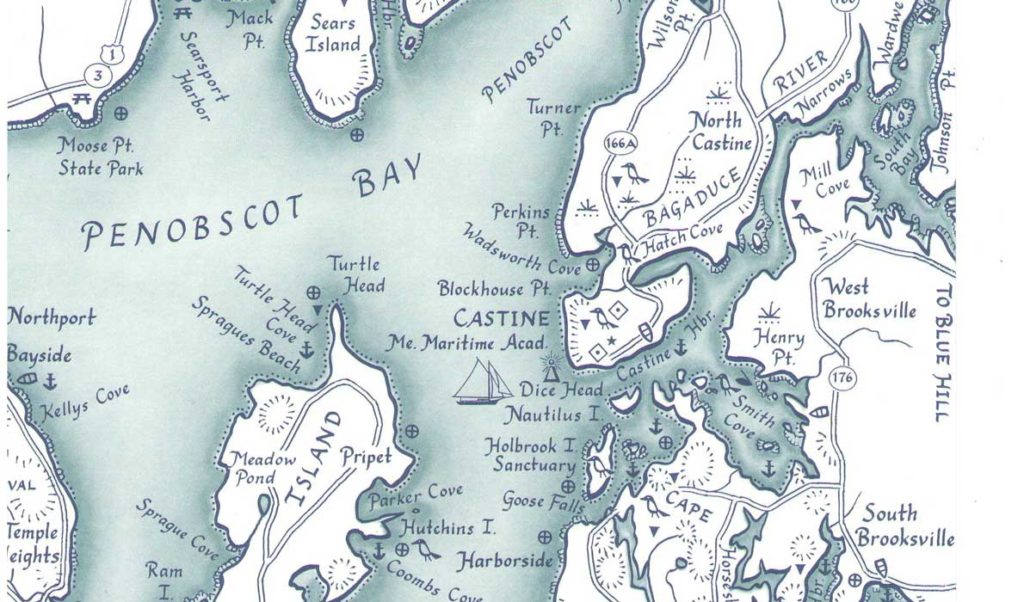

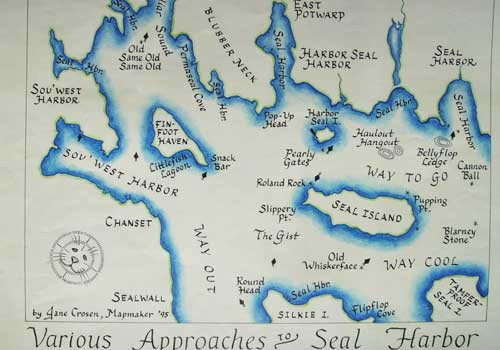

Crosen eventually turned down a lot of mapmaking projects so she could focus on making her own maps of Maine, mostly locations featuring water. Today, she is known for these “map portraits.”

The Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education in Portland has her map of Casco Bay and the Calendar Islands in its collection and included her and her map in a recent exhibit showcasing women in cartography.

What makes her maps unique is that she still draws them by hand, making her one of the only mapmakers today to create maps in such a traditional fashion. “The style of my maps is so simple and kind of lyrical,” she said, “that it brings out more of the landscape and less of the man-made features.”

Fictional places on a fictional map, by Jane Crosen

She uses her own calligraphy for the lettering on her maps and hand-drawn designs for all the symbols, icons and decorative elements. Instead of using a technical pen that makes lines of consistent width, she uses an artist’s fine paint brush and India ink to add appeal to the lines that shape her coastlines and watersheds, and she hand stipples or shades the water. These hand-drawing techniques and style choices, she said, set her maps apart because they honor the traditional styles of early cartographers, giving her maps a feeling of authenticity and intimacy.

CROSSING THE DIGITAL BRIDGE

Like Crosen, Belfast’s Margot Carpenter didn’t start her career in mapmaking; her background is in architecture and landscape planning. And like Crosen, Carpenter, 54, is trained in hand-drawing maps. Unlike Crosen, Carpenter has gone digital.

“When I first started working in maps,” she said, “hand-drawn was the only thing requested.” But, today, almost all her projects are created digitally. “A pure hand-drawn map is limited to the art world,” she said.

While she still offers hand-drawn maps as an option, she rarely has a client ask for it, but even those few projects with hand-drawing start out with a digital base of GIS data, she said. Her most recent projects include recreational maps for hikers and cyclists and roadside panels for the Maine Department of Transportation.

These are map projects that depend on accuracy, and accuracy is one of the best things digital technology can give clients.

“[Accuracy is] something that’s very hard to not want,” Carpenter said. “Everybody wants to have an accurate map.”

A map of the Schoodic peninsula by Margot Carpenter.

And since software tools, such as Adobe Illustrator, allow mapmakers to create a line that looks hand-drawn when it’s not, it makes sense to use them. “There are so many tools within the digital world to create a map with almost any kind of look,” she said.

THE FUTURE OF MAPS

“I hear all the time, ‘everything in the world has already been mapped,’” said Stephen Engle, director of the Center for Community GIS in Farmington.

The reality, he said, is that mapmakers can create dozens of maps for the same area, but each one will be different because they have different target audiences and purposes, and they are created by individual mapmakers with their own approaches to mapmaking.

“We all make maps but have different end goals,” he said.

The new era of mapmaking already under way—while dominated by digital interaction and data visualization—has room for everyone because the need for printed maps exists and will continue to exist.

“I do still believe there is an innate appeal of maps that is going to continue to drive individual interests in maps they can put on their walls, that they can take with them hiking—our phones are prone to lose battery,” he said.

So while the world of maps is becoming more digital and will only continue to be so, it won’t be at the expense of traditional maps, map design or mapmakers.

Interested in maps? Check out these map-related opportunities:

The Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education at the University of Southern Maine in Portland. Admission is free. If you can’t get to the library in person, you can view maps, exhibits and other items in the museum collection online. Go to www.oshermaps.org.

Mapping Brunswick: Charting Five Centuries of a Town in Maine. On Feb. 22, Jym St. Pierre, author of Brunswick Outdoors map, presents an illustrated lecture covering 500 years of Brunswick history through maps and charts. The lecture is part of the Pejepscot Historical Society’s Brown Bag Lunch series. Lecture is at noon; bring your lunch, cookies and beverages are provided. Admission is by donation. PHS is at 159 Park Row in Brunswick. Go to http://pejepscothistorical.org/events for more information.