Sen. Angus King’s analogy succinctly set the scene.

“It’s like the sudden discovery of the Mediterranean Sea,” King said, an early speaker in a day-long forum devoted to the Arctic at Portland’s University of Southern Maine on Oct. 3.

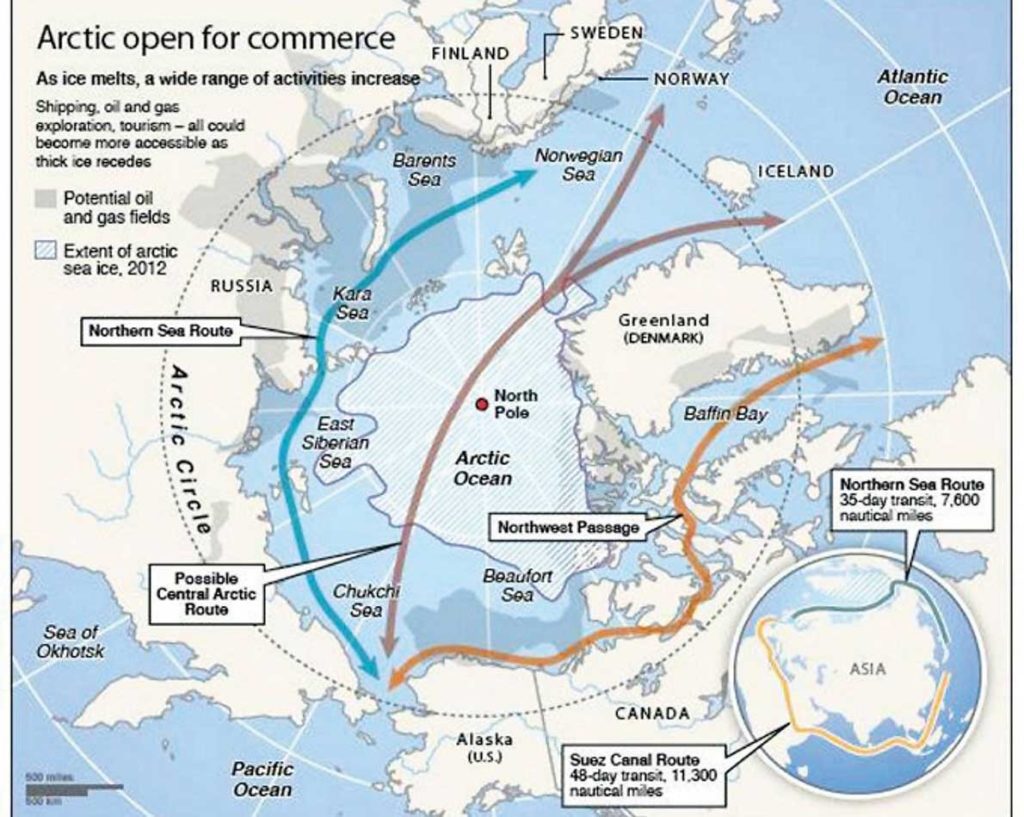

Though the Arctic region has been extensively explored, the rapid melting of sea ice has transformed the top of the world into a navigable—and exploitable—body of water. King noted that it took “a thousand years of wars” to settle conflicts in the Mediterranean region, and expressed hope that this would not be the case with the Arctic.

The Arctic Council, an international body formed in 1996 that functions like a mini-United Nations, discussing environmental and development issues in the region, was meeting later that week in Portland. Those sessions, which about 250 delegates were expected to attend, were closed to the public.

Holding the meeting in Maine reflected, in part, the chairing of the council by the U.S., a responsibility that rotates among the eight participating nations. But it also reflected the ties Maine now has with the Arctic. As the most easterly and northerly of the contiguous 48 states, Maine ports could become departure points for the long-sought Northwest Passage to Asia.

In his remarks opening the Oct. 3 forum, USM president Glenn Cummings noted the historic importance of that potential trade route, which was well understood by our ancestors, “many of whom died in pursuit of this passage.”

With shipping opening over the top of the world, Maine’s role in global trade could become far more significant.

“It may change our history,” Cummings said.

Eight nations make up the Arctic Council—Canada, the U.S., Russia, Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland—along with six groups representing the indigenous people of the region. A dozen other nations have been given observer status, including the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, South Korea and India. Speakers said the level of interest by nations not bordering the Arctic spoke to the high geo-political stakes of the changing environment.

Some four million people live in the Arctic.

King noted that he and eight or so colleagues in the U.S. Senate have formed an Arctic caucus to monitor emerging issues.

DISASTER AND OPPORTUNITY

The opportunity to move freight and people through the Arctic by ship could not be discussed without acknowledging that it was created by an environmental disaster.

King recounted a trip he took to Greenland during the summer with the commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, during which he learned that two-thirds of Arctic sea ice has melted since 1980. Though there is less ice, there are more icebergs, he said, which can make ship passage hazardous.

Just weeks ago, the nearly 900-foot-long cruise ship Crystal Serenity traversed the Northwest Passage, stopping in Bar Harbor and finally New York. But it was accompanied by a vessel with ice-breaking capacity, and helicopters that might have been used to evacuate passengers in an emergency.

Several speakers said plans for rescuing vessels or responding to spills in the Arctic have yet to be formalized.

“We’re talking ten to 20 years from now,” King said, before shipping could routinely pass through the Arctic.

Meanwhile, the senator and other speakers peppered their remarks with evidence of the calamity of climate change.

Miami is now experiencing what locals call “sunny day floods,” high tides that encroach on the city because of rising sea levels. Seas are expected to be a foot higher 15 years from now, and possibly six feet higher by the end of the century.

Rafe Pomerance of the National Academy of Sciences connected the dots: “The fate of Greenland is the fate of Miami.”

One metric spoke volumes: Paul Mayewski of the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute said on Dec. 30 of last year, the temperature at the North Pole was above freezing.

Paty Matrai of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences noted that there now are more plants growing in the Arctic, yet they are less productive. Fish continue moving northward into the region, she added, which may have political ramifications.

THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING

Russia borders more than half the Arctic Circle, and so it looms large in discussions about potential political conflicts in the region, especially over resource extraction.

David Balton of the U.S. State Department minimized potential conflict with Russia, but others were less optimistic. Balton spoke of the public order of the Arctic.

“There is an order, but it’s changing very rapidly,” he said. There is no threat of armed conflict, no terrorism, mass migration or narco-trafficking in the region, he added.

But the nations bordering the Arctic are claiming control over the sea floor.

“There is a process to determine which part belongs to whom,” Balton said, with lawyers, geologists and geographers weighing in.

A different assessment of Russia’s impact came from James Kraska, a law professor at the U.S. Naval War College.

“Russia is really the bellwether for the public order of the Arctic,” he said.

Of the region’s four million residents, two million are Russian. The country has 16 deep water ports and 13 air fields near or north of the Arctic Circle. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, insecurity is the mood of the country’s leaders, Kraska continued, which may have spurred the increased military presence—including six new bases—Russia has in the Arctic.

“I believe Russia is placing them here as sea routes open,” he said.