I was greatly disappointed to read that the new ferry being built for Islesboro has gone from an all-electric boat to a hybrid. With global warming affecting the Gulf of Maine faster than most other bodies of water in the world, I believe we need to make our best effort in new technologies, not a half attempts.

Switching a vessel to a hybrid as a rule only saves 10% of the fuel. There is a ferry in Norway named Ampere (formerly Zero Cat), which has the same length run as the Islesboro ferry (3.5 nautical miles) which has been operating for 13 years. It is reported that she avoids the use of quarter of a million gallons of diesel annually and offsets 570 tons of carbon dioxide and 15 tons of nitrogen oxide emissions compared to a conventional ferry on the same route. The Ampere carries 120 cars and 360 passengers.

The more carbon we put in the atmosphere, the more the atmosphere warms up, and the more acidic the oceans become. The oceans absorb roughly half the CO2 we pump into the atmosphere.

Electric ferries cost more to build, but they cut emissions by 95% and operating costs by 80%.

The more CO2 we pump, the more it turns to carbonic acid in the oceans. Lobster (not to mention scallops, mussels, and other crustaceans) cannot form shells in water that is too acidic.

There are lots of other electric ferries. Denmark’s Ellen is 200-feet long and completes a 22-mile trip five times a day. She is totally electric. There are no generators on board.

The Aurora and Tycho Brahe are two ferries that go between Denmark and Sweden that are 365 feet long. They, too, are totally electric. In Alabama, this country’s first electric ferry, Gee’s Bend Ferry, has been operating its two-mile route since about 2016.

Electric ferries cost more to build, but they cut emissions by 95% and operating costs by 80%.

The technique used by all these ferries to charge their batteries quickly without causing local brown outs (or worse) is to use a battery pack on shore. On the Islesboro to Linconlville run, the battery on shore would have 45 minutes to charge. The ferry would have battery capacity to run both ways if one charging system is out.

But what if there is a power failure, which has been known to happen both in Lincolnville and Iselesboro? There are already diesel generators at both ends to run the ramps in case of a power failure. These would probably need to be increased in size to provide enough power to get the ferry safely back to the other side. I estimate they would need to be between 150 kW and 200 kW.

Most merchant ships today have reduced their cruising speed. The 950-foot U.S. Navy boat I was on went 23 knots with four engines and 18 knots on two engines. As fuel has gotten more expensive, ships have slowed down.

In my opinion, the 13 knots that the Margaret Chase Smith cruises at is too fast. Cruising at ten knots would save a lot of fuel. That would throw the schedule off, but we would adjust.

All-electric ferries have been operating for 13 years in other countries and seven years in this country. We can always find excuses not to do something. But that is not how this country has evolved. And that attitude will drive away young people who will begin to get the message that we can’t do it here. This is what I saw in Argentina.

But in this case, it is our children who will bear the brunt of our decision. For their sake, we need to make our best efforts.

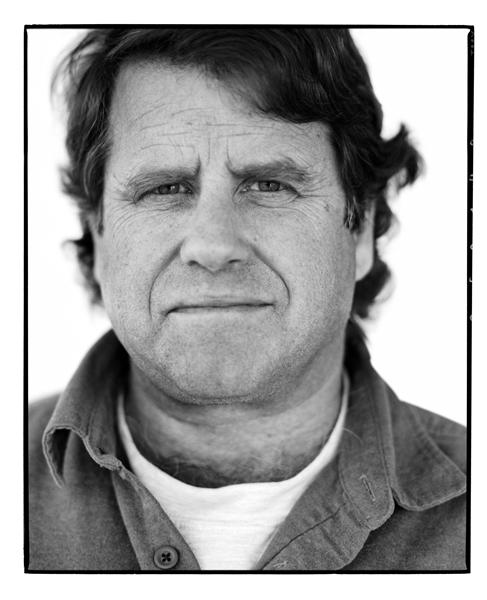

Peter Willcox has been a merchant sailor for 52 years, including 44 years working for environmental groups. He lives on Islesboro.