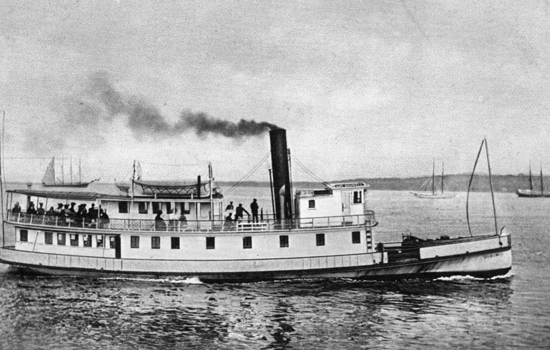

The SS Governor Bodwell, seen here, was launched at Rockland on May 27, 1892, by the Vinalhaven & Rockland Steamboat Company. It ran between the island and Rockland from 1892 to 1924. PHOTO: COURTESY HISTORY PRESS/VINALHAVEN ISLAND’S MARITIME INDUSTRIES

By Nancy Griffin

The allure of living on an island includes isolation from the rest of the world. The downside of living on an island includes isolation from the rest of the world. Especially when you need something on the mainland.

That’s what ferries are for.

“We are the roads to the islands. We want to get everyone home,” is how Mark Higgins, manager of the Maine State Ferry Service, based in Rockland, explains its role.

Of course, ferries don’t merely perform the vital function of getting everyone home. They also bring tourists, freight, in some cases the mail, and much more to the islands.

“Island dwellers depend on water transportation, directly or indirectly, for everything,” said Maggy Willcox of Islesboro. “Pet needs a vet? That’s a trip to the mainland. Don’t have a friend that can give a decent haircut? That’s a trip to the mainland. Our health center and EMS are first rate, but when you have need of an ER, there is a ferry (or a helicopter) ride involved,” she said.

“There’s no dentist here. No bank. Need a tank of propane? That comes over on the ferry.”

While islanders save trips by buying online, “Whatever you purchase to save yourself a trip to the mainland still ships either via UPS or the U.S. Postal Service via the ferry. If you don’t have your own boat, you have to buy a trip on another,” said Willcox.

The ferry service was officially established in 1960 by the Maine Legislature, which in 1957 had charged the Maine Port Authority with creating a state service. The Penobscot Bay islands of Vinalhaven, North Haven, and Islesboro, and Swan’s Island off Mount Desert Island, were named in the original bill, Their needs were determined by a study of each island’s traffic, commissioned by the Maine Port Authority.

Each, of course, had vessel service prior to the state stepping in, but some islanders—particularly two from Vinalhaven—believed their water-rimmed outposts needed an improved service that could only be provided by a state-run system.

FOUNDERS

“My grandfather and Everett Libby helped create the Maine State Ferry Service,” said Phil Crossman of Vinalhaven. His grandfather was Edwin Franklin Maddox, descended from an ancestor who arrived on the Mayflower twelve generations before. Although a native of Blue Hill, not Vinalhaven, when Maddox was a young man he hopped aboard a wooden steamer that traveled from Boston to Maine, got off on Vinalhaven, spotted a beautiful young woman, “and just stayed.” He became a pillar of the community, “An institution here, in charge of everything, including the Masonic Lodge,” Crossman said.

Libby was a local businessman who was “widely admired and respected, thoughtful and deliberate. They were friends,” he said of the two men, “both selectmen and community leaders.” A hint of Libby’s importance to the service: the first new Vinalhaven ferry was named the Everett Libby.

Capt. Charles Philbrook at the helm of the ferry Everett Libby. PHOTO: COURTESY MADELAINE PHILBROOK HILDINGS/HISTORY PRESS/VINALHAVEN ISLAND’S MARITIME INDUSTRIES

“They likely recognized the opportunity more service would provide,” said Crossman. At the time, the 64-foot wooden vessel serving Vinalhaven’s 1,500 residents accommodated only two cars. In 1959, only 544 cars made the trip during the entire year. The vision of the two friends was borne out after the new service and new ferry took over. In 1960, 1,704 vehicles made the 13-mile crossing during June and July alone.

North Haven’s old 64-foot wooden ferry serving the 500 year-round residents could carry only one vehicle at a time and lacked the cargo-handling, two-ton hoist of the old Vinalhaven vessel. Each of these islands had a port district that owned and operated their respective ferries out of Rockland. When the new, 90-foot, aptly named North Haven was placed in service, vehicle traffic for the 11-mile trip increased from 290 cars for all of 1959, to 829 vehicles during June and July of 1960.

In the late 1950s, Islesboro, just a three-mile trip from Lincolnville, boasted an 84-foot, 10-car, double-ended wooden ferry that could carry trucks. The State Highway Commission built and maintained the mainland and island terminals. More than 7,000 vehicles crossed to Islesboro in June and July of 1960 on the new 119-foot Governor Muskie.

Swan’s Island’s old ferry was privately owned. The 44-foot Sea Wind served McKinley—current day Bass Harbor—and Swan’s Island by way of Frenchboro, for a round trip of just over 22 miles, making one trip a day year-round since 1950, carrying mail six days a week but no vehicles. When the William S. Silsby took over the run, 2,074 vessels made the trip in June and July.

The Maine Port Authority’s report to then-Gov. Reed explained the new service’s mission and approach: “In considering the particular type of ferries and terminals to be constructed, the Directors of the Maine Port Authority, in conjunction with the Advisory Board, appointed by the Governor, took into consideration not only the present, but the probable future demands for these ferries.” Considerations included taking care of the huge upsurge in summer traffic, making sure vessels could handle the largest trucks then allowed on Maine highways, that vessels could safely dock fully-loaded at “dead low or dead high water,” planning for winter conditions, heavy seas, and 13-foot tides.

Originally, North Haven selectmen said they wanted a side-loading ferry because they believed a bow- and stern-loading vessel would obstruct the marine channel. But before new vessel construction began, they changed their minds when they realized they needed to be able to bring trucks over.

A bit of an uproar occurred when the contract was awarded to build the first four ferries. An out-of-state boatyard—the Wiley Manufacturing Company of Port Deposit, Maryland—won with a “substantially lower” bid, according to the report. Wooden vessels were ruled out by U.S. Coast Guard regulations that required nonflammable construction materials for a boat transporting vehicles. Today, the Maine State Ferry Service is building a new boat at Washburn & Doughty, an East Boothbay shipyard established in 1977, for delivery in the fall of 2020.

FERRIES CHANGED ISLANDS

For every silver lining, there’s usually a cloud. Before the new ferry with its expanded vehicle capacity, Vinalhaven had more shops.

“Until then, Vinalhaven was captive because of isolation from mainland, but also, Main Street was thriving because of it. There was a kind of economic wonderland on Main Street,” said Crossman. Residents traveled to the mainland more often to stock up on supplies, so, in a Catch-22 scenario, now they have little choice.

Things were and are different on Matinicus, another year-round residential island in Penobscot Bay. Eva Murray, a resident for more than 30 years, said the private, one-car, freight and passenger vessel serving the island was good enough for a long time.

“We had less need. People didn’t go back and forth as much,” she said. “We had the mail boat. We had island ‘beater’ cars that never saw an inspection sticker. We had other private vessels, usually old sardine carriers, that would bring lumber and other stuff,” Murray recalled. “But we also had a solid waste problem.”

When the wooden mail boat grew too old and unrepairable, its service ended in the mid-1970s, so islanders petitioned the ferry service to expand service to Matinicus.

Matinicus, the most seaward Maine island at 22 miles offshore, has different needs and challenges than the other 14 inhabited Maine islands. The only existing ferry that can manage the island’s harbor and wharf is the Everett Libby. A wharf that could handle larger ferries needing a deeper draft would have to extend so far out into the harbor that its other uses would be curtailed.

The trip from the mainland takes two hours, with another hour to unload. The ferry must come and go on a high tide and between the hours of 7 a.m. and 4 p.m. These requirements place a serious limit on the number of annual trips.

“The schedule looks random, but it depends on the tides and hours, and contractors like to have a day between round trips because they don’t want to leave their trucks for a month,” said Murray. “Our wharf is hidden at low tide.”

Ferry trips totaled 34 trips in 2018.

“To make trips when you want to would cut the harbor in half, mess it up. It’s our only economy, fishing,” said Murray. “We can’t sabotage our harbor.”

In recent decades, air service has begun supplanting the ferry.

“On other islands, they eat, sleep and breathe by the ferry schedule,” said Murray. “The word ‘lifeline’ is used. But the flying service is more of a lifeline for us.” Many residents, like Murray, have a pilot’s license. Penobscot Island Air out of Rockland delivers the mail and makes regularly scheduled trips.

The infrequent ferry has proven a boon for getting rid of the island’s solid waste and Murray, 2018’s Maine Solid Waste Manager of the Year, is the one driving the truck off-island to Rockland at 16 or 17 times a year. “I’m probably the island’s most frequent ferry user,” she said. Her husband Paul is the island’s propane dealer. It’s impossible to bring bulk propane, and delivering 100-lb. cylinders requires a ferry to carry trucks and meet stringent regulations.

NO CARS

Monhegan Island, like Matinicus, usually has a winter population between 30 and 40, but the island does not have a regular car ferry. A few of the lobstering residents have trucks, but most residents use golf carts or just walk. The Laura B was put into service in 1952 by the founder of the Monhegan Boat Line, Capt. Earl Fields Sr. The former U.S. Army T boat, now owned by Capt. James Barstow, still makes the trip, joined by a bigger, newer vessel during the summer tourist rush.

“All 15 inhabited islands have different transportation realities,” said Murray. “There’s no such thing as ‘the islands’ when it comes to transportation issues.”

Seven islands of Casco Bay—Peaks, Little Diamond, Great Diamond, Long Island, Chebeague, Cliff, and Bailey— are served by Casco Bay Lines, a thriving private service at the time the Maine State Ferry Service began, but which foundered and went bankrupt in 1981. The quasi-municipal Casco Bay Transit Lines District took over the existing lines and ferries. It’s governed by a board of 12 directors who serve three-year terms. Fares are regulated by the Public Utilities Commission.

Mark Higgins, a Dover-Foxcroft native and 1992 graduate of Maine Maritime Academy, has headed up the Maine State Ferry Service for nearly two years. He finds the work more exciting than his previous tenure with American Dynamic in far-flung places such as Africa and Norway.

“We have 100 people working for the service, seven boats going all the time. The biggest challenge is having enough hours in the day, and no two days are alike,” he said. “For me, the service is indispensable, vital to Maine people as well as the economy. Islands are a big part of what makes Maine special. It’s a way of life. It’s important to provide service to people with the least disruption.”

Nancy Griffin is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Thomaston.