One hundred years ago, as the U.S. ramped up its involvement in what was sometimes called the “War to End All Wars,” the city of Bath had a problem. Its population was exploding as thousands moved to the city to work in the shipyards as part of the war effort.

But there was no place to put them.

The solution to that long-ago problem still impacts the city today.

STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

Andrews Road today.

A lecture in late November at Maine Maritime Museum in Bath in conjunction with the museum’s exhibit, “Pull Together: Maritime Maine in the 1914 to 1918 Great War,” explored the effects of two worker housing projects—the North End and Lincoln Street projects—on the city.

At a time when most people did not have cars, workers lived close to places of employment, said Robin A.S. Haynes, the Bath-based architectural historian who gave the museum lecture, speaking in an interview after her presentation.

Unlike during World War II when workers were bused to Bath Iron Works three times a day from places such as Rockland, no transportation system supported shipyard workers during World War I. Instead, the workers and their families moved to the city.

With not enough housing in Bath, people got creative (and, in some cases, greedy). They turned barns into apartments, crammed people into rooms in houses all over town, set up tent cities outside the shipyards, and lived on house boats on the river, she noted.

But these stop-gap measures, and a few small, private housing developments such as Snow Park and Washington Park, barely made a dent. The population of Bath went from 9,396 in 1910 to, by some estimates, between 18,000 to 20,000 in 1917-1918, she said.

STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

The so-called Brick Project as it looks today.

The federal government recognized the problem in Bath—and in cities and towns across the country where industries supported the war effort—and allocated funds to build worker housing.

Construction of the North End and Lincoln Street projects, known more commonly as the Brick Project and the White Project respectively, began in August 1918, and although built in record time—97 days for the Brick Project—they ultimately came too late for the workers.

The war ended in November 1918 with the worker housing projects uncompleted. Within three weeks of the signing of the armistice, said Haynes, a newspaper account indicated that 1,200 people had already left the city.

Some shipyard workers did move into the housing projects while war contract work wrapped up through 1921, but by 1930, the population had returned to its pre-war levels, at 9,110.

CHARACTER REMAINS

Today, the White Project, and, especially, the Brick Project, because of its distinctive brick construction, slate roofs, and British-townhouse aesthetic, are more than just historic, picturesque neighborhoods in the city of Bath, said Andrew Deci, the city’s director of planning and development.

“They’re special pockets of character in an already character-rich community. They are unique and they’re beautiful and people love them,” he said.

But on a more practical level, they make Bath attractive to home buyers who represent the current trend of wanting to live in smaller homes on smaller lots in walkable/bike-able neighborhoods where they know their neighbors and there’s a sense of community, he said.

That Bath has existing housing that fits with what is competitive on the real estate market today is lucky, he said, because it would be difficult to build comparable housing in the numbers that already exist. “It’s offering a product that we wouldn’t have otherwise,” he said.

And it’s housing stock that is affordable and growing in value, said Patty Sample Colwell, a real estate agent with Bath-based Sharon Drake Real Estate, making these Bath neighborhoods even more desirable to retirees, young professionals or those seeking starter homes.

Despite being 100 years old and built in a hurry, the construction of the homes is durable and they have visually-pleasing details, she said, such as hardwood floors and nice placement of windows to let in natural light and offer cross-ventilation.

A home in the Brick Project that valued at $115,000 a few years ago that has had some renovation in the intervening years may sell for $130,000 or $132,000 today, she said.

PHOTO: COURTESY MAINE MARITIME MUSEUM

The Brick Project in the early 20th century.

“For (buyers) to find a house that is under $150,000 that has all these attributes, I think, is highly unusual,” she said. “If you want to spend under $150,000, these houses are a great investment. If you do fix it up the money (you invest) will come back to you.”

The Brick and White projects also serve to inspire the city’s leaders and planners in how they approach future development, said Deci.

“I would say these historic projects remind us of our need to have attention to quality of design,” he said. It is important where projects are located, he said, but just as important is how they look, how well they are built, and how much they foster community.

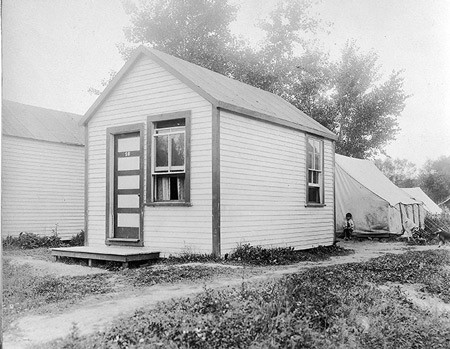

PHOTO: COURTESY MAINE MARITIME MUSEUM

Worker housing in Bath during the World War I years included hastily built small structures and tents.