What thou lovest well remains,

the rest is dross

– Ezra Pound, Canto LXXXI

In the blue distance of inner Casco Bay, the smokestacks of the Cousins Island power plant could be seen poking into the sky. This was in 1980, looking northeast from the alcove window of a third-floor apartment on the Eastern Promenade in Portland, where I lived that summer.

East of the smokestacks was a strand of white beach. This marked Little Chebeague Island, where I had never set foot. Beyond were the green-black shadows of Great Chebeague, where I had set many feet. It looked uncapturably, wistfully far away. More like an echo off the water than a real place.

The Eastern Abenaki word transliterated “Chebeague” means, according to various sources, either “wide expanse of water” or “island of many springs” or “separated place.” Any of these will do, but the last rings truest because the root is “sebe,” meaning divided or almost-through, with the suffix “-ague,” meaning beneath: Great and Little Chebeague Islands are connected at low tide by a sandbar that goes beneath the water when high tide divides them.

In the mid-1950s my father, mother, little sister Heidi and I lived there. My father commuted by boat to his construction job at the power plant being built on Cousins Island. He ran a flat-bottomed punt to work, I knew—or at least, remember knowing.

Sometimes I rode in the bow of that punt looking down into the clear water at the sand rushing along beneath. The bottom bang-banging on minor chop, the spray, and the smell of the salt sea. Was it too late to beat the tide? Would we run aground?

One day we made the trip to Cousins Island and then to Portland, where I got a plastic boat in a department store, maybe W.T. Grant’s. When we got back to the house we lived in somewhere on the east side of the island, I realized I had left the little orange boat in a brown paper bag on the ledges at Cousins Island. I knew exactly where it was, lying there in the bag. Maybe I could still find it now.

There was no going back that night. Maybe that was the first of ten thousand sleepless nights. Soon after, we returned across the gleaming water. I scrambled along the ledges and to my astonishment and relief, the bag was exactly where I left it.

SMITTY’S TAXI

The name “Smitty” was often spoken in connection with boats, and I suppose my father, along with others, had a deal with Jasper Smith to ferry them to Cousins Island when the weather or the tide was wrong. The Chebeague Transportation Co.’s website tells me Smitty “began operating his water taxi between Cousins and Chebeague Island in 1959 using the Polly-Lin, a converted 36-foot lobster boat.” The name Polly-Lin strikes a mythological chord in my memory. But the date—I’m not sure.

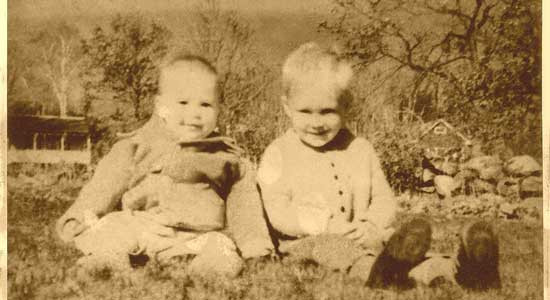

A family photo shows my sister at the age of about six months, and me, two-and-a-half, sitting in a field on Chebeague. This must have been the day in 1955 when autumn was created in me. Scrambling around in acorn-smelling woods. Stiff brown dry-smelling grass. Chilly, the sun bright in blue, blue sky. For 60 more Octobers that day has resonated like cosmic background radiation.

We had moved there from Massachusetts, my father’s home base, and where Heidi and I were born, to my mother’s native Portland. My father’s vocation of the moment was flying a seaplane. The sardine seiners hired him to spot the herring that on summer evenings gathered in dark oval schools easily seen from a few hundred feet aloft. He’d report back, angling the plane in over shale-flat twilight water and taxiing to the boats.

Dana Wilde and sister

If fish were in one of his seiners’ dory-marked coves, they’d steam out, spend the night setting and hauling nets, and cut my father in for 10 percent of the take. This was summer work, though.

Construction on the William F. Wyman Station Unit 1 began in October 1955, according to the Maine Historical Society’s archive. It came on line in 1957, the year we moved back to Portland and my twin brothers were born.

The problem of crossing the expanse of water to Cousins Island must date from 1955 or 1956. Maybe Smitty was running the Polly-Lin ferry earlier than anyone but me remembers. I remember the diesel hum of his boat. And the Casco Bay ferries. The Nellie G, warm and cozy, chugging to Chandler’s Wharf. The Emita, rattling and vibrating. The seining boats with fish-scale decks, suction hoses and warm galleys with coffee (not for kids).

Mythic to me was the Sirius, a lobster boat by design, but larger, cleaner-lined and equipped for seining. It belonged to one of the fishermen my father flew for. The Sirius had an otherworldly presence, and so did that fisherman—his tall frame in oilskins and turned-down rubber boots carrying gear up the Bennetts Cove beach and laconic goodwill towards me, something I hardly ever registered among adults.

He took root in my mind as a prototype of what strength and wisdom look like.

SCANT HERRING

By 1960, the herring were declining. I remember agitated discussions about purse seiners. The fishermen cut my father’s services loose—the catches became so scant and far between they could no longer spare the 10 percent to gain the edge.

My father turned the seaplane into a tourist ride. We spent summers flying from a reed-choked berth at Great Pond in Cape Elizabeth to Mackerel Cove at Bailey Island. We spent an autumn weekend each on the wharves at Long Island, Peaks, Cliff, Cousins and Chebeague’s Chandler’s and Stone wharves, giving cut-rate rides to whoever had overstayed Labor Day.

While my father flew, I prowled the docks like a figure out of a Longfellow poem—“the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts”—and at Chandler’s Cove memories resonated deep in my 10-year-old mind. I tried to recapture a moment at the age of three of clambering on the barnacled, seaweedy rocks beside the wharf. In the clear green water near the pilings scuttled horseshoe crabs, ancient beyond comprehension. Across the cove, on Indian Point, almost to the sandbar, a huge tree with an umbel-like top stood silhouetted. What kind of exotic tree is that?

When I gazed in 1980 from my little writing alcove on the Eastern Prom toward the smokestacks of the recently activated Wyman plant Unit 4, that tree vibrated in memory. A year later some friends and I rode the ferry to Chandler’s Cove, trekked with backpacks around the beach, and found it was, of all things, an oak. We walked the unkempt paths on Little Chebeague and camped. They were by then islands of many memory springs.

The physicists say the arrow of time travels in one direction only. The past is irretrievably behind.

But Einstein clarified that, contrary to appearances, time is not a flow: It’s a dimension. The October field, the Indian Point tree (gone now), the shuffle of horseshoe crabs, the throb of diesel engines, a fisherman and his mythic ship—they all have locations, like distant islands. This is a fact of physics.

For unknown reasons, the time dimension seems to be in motion and events are capturable only once. But the feelings vibrating out of them resonate forever, like sound waves.

Somehow the tides of time divide us from the fathomable past. And then beneath, you find they also connect autumns past to the unfathomable spring of now, and on.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy northwestern Waldo County. He writes the Backyard Naturalist column for The Central Maine Morning Sentinel and the Kennebec Journal; his work on Maine’s natural world is collected in The Other End of the Driveway, available from online booksellers or by contacting the author at naturalist@dwildepress.net.