Coastal Maine continues to reel from the effects of back-to-back January storms that caused long-lasting damage to working waterfronts, homes, areas of leisure, as well as cultural heritage sites. By nature of their location, lighthouses and their supporting structures are especially vulnerable to the destruction caused by extreme winds, surf, and tides. While each site varies in size and complexity, they feature more than lighthouses themselves.

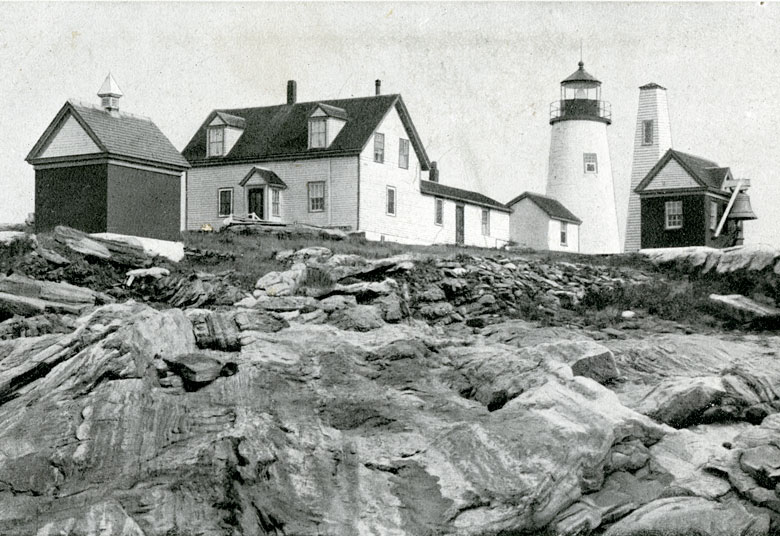

A keeper’s dwelling, boat house, oil house, and fog signal are frequently found alongside our beloved towering beacons, each building having played a role in support of coastal navigation.

One of Maine’s most prominent lighthouse stations, Pemaquid Point has been frequently featured in news coverage documenting the storms’ aftermath. A striking image of the modestly-sized bell house is shown with two of its brick walls caved in, with a large bell among the rubble. This bell has not been heard since the 1930s, but it was once part of a complex system of fog signals meant to assist mariners during low visibility.

The automated bell-striker was first powered by engines inside the bell house.

The Pemaquid fog signal bell is pictured here early in its history on a postcard dating to about 1905. While a lighthouse has been present at this site since 1827, the fog bell was not installed until 1897.

The automated bell-striker was first powered by engines inside the bell house. This was then converted to a wound mechanism; the height of the thin tower behind the bell house was required for weights to drop and keep the mechanism going.

Like the light emitted from towers, fog signals also have unique patterns assigned to them. The Pemaquid Point signal struck once every ten seconds once activated.

Sound signals were first introduced on the New England coastline in the 18th century to aid low visibility, with cannons serving as the first prototypes. Bells followed, then compressed air trumpets were introduced not long after. In some versions, horses were utilized to create the air pressure. New signal types, and methods of powering them, were continually developed including whistles, sirens, diaphones, and horns, each having a part in developing a sense of place in the communities where they were installed.

In reality, no style of fog signal is particularly helpful. Anyone who has spent time on the open water can confirm the difficulty in determining what direction a sound is coming from. Additionally, atmospheric conditions affect how far sound can travel.

The Lighthouse Service’s annual List of Lights and Fog Signals even stated the following: “conditions for hearing a signal will vary at the same station … therefore mariners must not judge their distance from a fog-signal station by the force of the sound.”

In addition to a lack of efficacy, the common use of precise electronic LORAN and GPS systems have negated the need for many traditional navigation tools like fog signals. Even so, the bellowing of fog signals can still be heard. However, what used to be a constant for the duration of a foggy day, is now activated on demand by mariners via VHF-Radio. Maine converted to this system in 2016, leaving a noisier past behind.

Kelly Page is curator of collections at Maine Maritime Museum. A new exhibit at the museum further explores the past and present of soundscapes; Lost and Found: Sounds of the Maine Coast by Dianne Ballon is on view through November 2024. Explore resources and plan your visit at www.mainemaritimemuseum.org