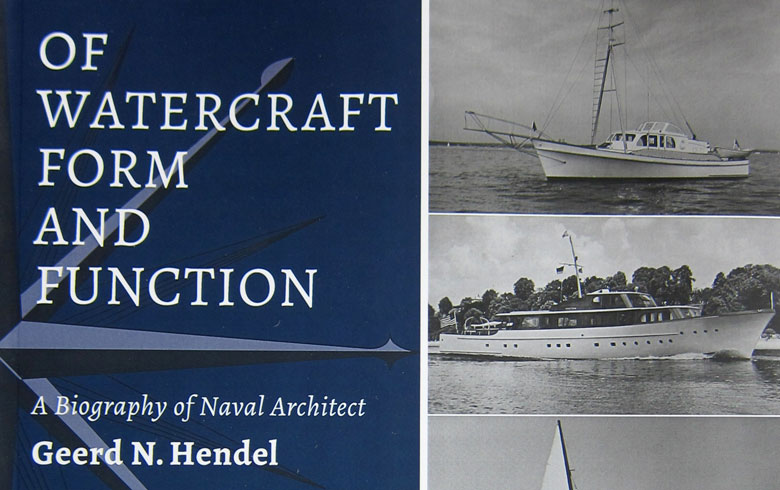

Of Watercraft and Function: A Biography of Naval Architect Geerd N. Hendel

By Roger Allen Moody

A documented, remembered career is a form of immortality. A career as long and distinguished as that of Geerd Hendel, the German-American naval architect who worked in New York, Boston, Bath, and Camden deserves a well-researched biography, and now Roger Moody has provided one.

Hendel died at the age of 95 in 1998, leaving behind a wealth of material now in the possession of the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath. Moody’s biography is based on this collection plus other material made available to him by family members who still live in Maine. As part of his research, Moody also interviewed people in the maritime world who had known Hendel, giving this book a contemporary feel in addition to all the documentation.

Hendel was an early advocate of aluminum as a boatbuilding material…

What’s most striking about Hendel’s career in Maine and elsewhere is its diversity: he designed or worked with others on projects ranging from Ranger, which won the America’s Cup in 1937, to “boom jumpers” for paper company log drives in the 1950s. His designs included large and small motor and sailing yachts, fishing trawlers, tugs, and lobster boats.

He worked on designs for submarine chasers and landing craft during World War II. In 1930, during an early stint with Bath Iron Works, he was part of the team responsible for Corsair IV, the last yacht BIW built for financier J.P. Morgan and—according to Moody—the largest yacht ever built in the United States.

Hendel was an early advocate of aluminum as a boatbuilding material, and designed a 26-foot sloop named Whistler, built in aluminum in 1939 at Rice Brothers in East Boothbay. After an unfortunate start—the boat sank not long after launching due to electrolysis between a copper mast-step penny and the aluminum hull, causing a hole in the hull—Hendel owned and sailed Whistler for 30 years.

In his book, Moody documents Whistler’s subsequent career in ads for Alcoa Aluminum as well as her decline in a Winterport boatyard. Today, Moody reports, Whistler rests, keel-less, in a field in Monroe—a sad fate for a pioneering boat.

Hendel’s aluminum experimenting continued, but he also continued designing in other materials. His Boothbay Harbor One Design was built in wood, while the subsequent Christmas Cove One Design was done in fiberglass.

Moody attributes Hendel’s knowledge of fishing draggers and trawlers—something of a specialty for him in the 1930s and after World War II—to his early years at Bath Iron Works. Most of these vessels were wooden and included trawler-type boats designed for uses other than fishing, such as Sunbeam III for the Maine Seacoast Mission.

Over the years, these designs led to various vessels for lobstering and recreational purposes, built in wood and fiberglass. The work in aluminum continued, as Camden Shipbuilding undertook the construction of a series of 18-foot centerboard daysailers designed by Hendel.

Prior to 1972, millions of logs were floated down rivers and lakes to Maine lumber and paper mills. All this activity required vessels to tow and control huge “booms” of logs on lakes and rivers. Hendel designed numerous log-boom tugs and towboats for Central Maine Power (proprietor of Harris Dam, through which many logs had to pass), Great Northern Paper Co., and Brown Paper Co. In addition there were harbor tugs and a small icebreaker.

Prior to 1972, millions of logs were floated down rivers and lakes to Maine lumber and paper mills. All this activity required vessels to tow and control huge “booms” of logs on lakes and rivers. Hendel designed numerous log-boom tugs and towboats for Central Maine Power (proprietor of Harris Dam, through which many logs had to pass), Great Northern Paper Co., and Brown Paper Co. In addition there were harbor tugs and a small icebreaker.

Then there were the boom jumpers, several of which were designed by Hendel. Moody turns the description of a boom jumper’s job over to longtime Maine columnist Lew Dietz:

“It took a special boat and a special man for the tricky job of jumping booms…in due time there were men with the cowboy knack of handling them. When it was necessary to get inside a boom, the boat was headed directly at the barrier, throttle wide open. The trick was to hit the boom with the bow up so that the boat would rise smoothly on her forefoot and slide over the obstacle in one splashing leap.”

When Great Northern Paper’s longtime boom expert, O.A. Harkness, retired in 1950, Hendel took on design chores for Great Northern including several boom-jumpers and tugs, built in welded steel. The inland towboat business dried up after Maine banned log drives in 1972.

This is an ambitious book, capturing the many phases of Geerd Hendel’s long career, from a partnership in his early years with yacht designer Starling Burgess to yachts on his own, to fishing boats, lobster boats, tugs, towboats, and Hendel’s important experimentation with aluminum and other materials.

Near the end of his book, Moody includes two pages of a resume Hendel wrote in 1989, when he was 86 and had retired. Well over 50 years at the drawing board, “with the last 30 managing my own firm,” Hendel wrote, “I found my work rewarding, not a burden, met interesting people, and also made friends doing it.”

A modest summing-up by a man whose achievements speak for themselves: immortality, well deserved.

David D. Platt is former editor of The Working Waterfront.