By Dana Wilde

Long ago, before realizing I was unfit to write poetry, I set myself a project I thought might become my life’s work.

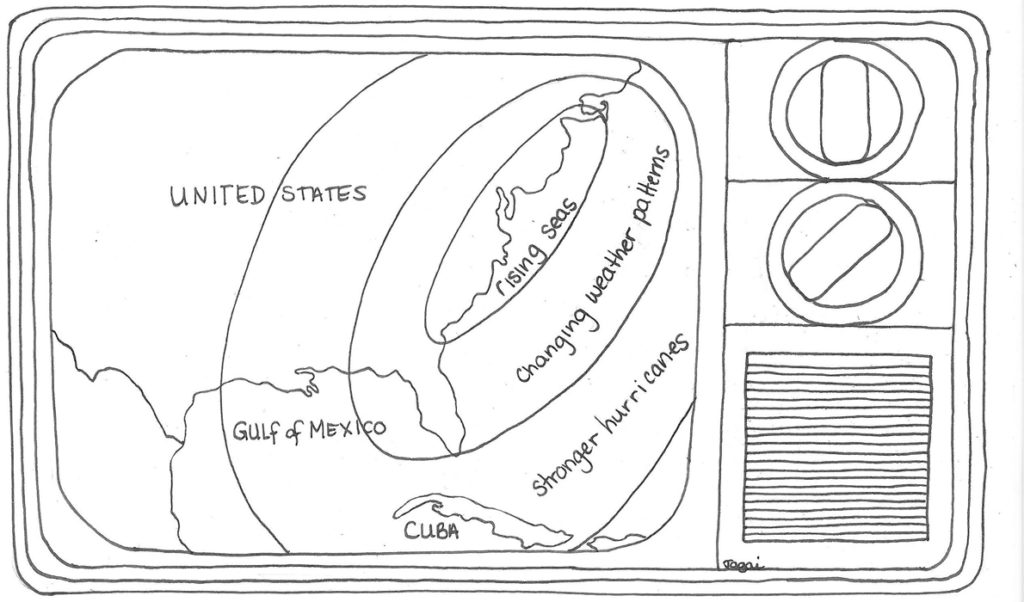

My childhood was still fresh and glistening with pain, and one of the more frightening disturbances had been the Cuban Missile Crisis, when I was 9. Burned into me were, and are, TV news maps of the East Coast. On the maps, concentric circles radiated from the middle of Cuba. One circle reached to Miami. Another reached to Washington D.C. The outermost circle reached to Massachusetts. They represented the range of ballistic missiles carrying nuclear warheads.

It seemed like we might be more or less safe on Casco Bay. But then there was the fallout. A single particle of radioactive dust could sicken and kill you. Billions of them would blow our way if the Reds launched a nuclear strike. It was common knowledge that a worldwide nuclear war would destroy the planet. Or at least, civilization.

These are heavy thoughts and feelings for a child.

When I was in college, the nuclear threat had not gone away. In the late ’70s, there was a lot of anti-war-based tension over Jimmy Carter’s proposal to deploy the neutron bomb in the U.S. military arsenal. The great thing about the neutron bomb was that, compared with regular nuclear bombs, it would do minimal damage to buildings and property while efficiently killing huge numbers of people with a special kind of radiation.

This made the world seem more insane than ever, which is a heavy feeling for an adult.

“In such an ugly time the true protest is beauty,” said a liner note on a Phil Ochs album. I decided to try to use the most beautiful form of language, poetry, to try to make a gesture that in its own way might help sand down the rough possibilities of nuclear catastrophe. This would be a long series of poems with the title Nuclear Cantos. I started writing from nowhere, which I often did in those days, and immediately discovered that although I had a good bead on the feelings and thoughts of nuclear insanity, my knowledge of nuclear weapons and war was superficial at best. So I started reading about it.

The reading turned out to be the project’s downfall. Just the basic facts were excruciating. Estimates at the time were that 9.5 million people died in World War I, about 10 percent of them civilians, and that about 55 million died in WW II, about half of them civilians. In the Korean War, I read, up to 90 percent of the casualties were civilians. It was excruciating.

How nuclear bombs work. Excruciating. How much damage a 2 megaton bomb does compared to a 20 megaton bomb. Excruciating. What Hiroshima looked like (a flattened wasteland) after the explosion there Aug. 6, 1945. Excruciating. How the 15 kiloton explosion of Little Boy over Hiroshima was 80 times smaller than the 1.2 megaton explosion of Fat Man on Nagasaki three days later. Excruciating. A nuclear explosion’s effectiveness when detonated in the air instead of ground level. Excruciating. How the explosions work. Their short-term and long-term effects. Excruciating.

“NO SOULS CAME FROM HIROSHIMA,” James Merrill had written in his poetry, and this seemed spiritually frightening enough to compel me to do my part and keep writing. After a while I noticed an atmosphere of heavy depression always developed during the times I tried to work on my cantos.

A book about nuclear winter effectively ended the project. The destruction not only of people and civilizations, but of the ecology of the whole planet at the hands of insanity was too horrible to hold in mind without going insane myself. “Stupidity carried beyond a certain point becomes a public menace,” another poet had written during World War I. I think the remains of the Nuclear Cantos are in a box in a closet. I’m not sure.

I write a column for some local newspapers called Backyard Naturalist, which for years has been about the many facets of natural beauty and its science. In the past few years the topic has sometimes divagated from the wisdom of the Phil Ochs album, to threats to the environment. I do not have fun writing about the threats. Almost no beauty is available there. It’s excruciating to report, for example, that high-temperature records are almost routinely being broken now summer after summer.

To report the relentless ways the Trump administration finds to pretend climate change is not happening.

It’s happening. Right before our eyes. And it’s going to get worse, as David Wallace-Wells in his well-researched book The Uninhabitable Earth and Bill McKibben in Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? both show.

We are literally at the edge of an ecological catastrophe at least as devastating as nuclear winter, with the added trouble of not being hypothetical. The insane thing is, we caused it and are continuing to push it along. The 2100s, even in the best-case scenarios in which we suddenly halt all carbon emissions, are going to be a “century of hell” for human beings, Wallace-Wells says.

The people who can see what climate change is going to do suffer from a psychological condition recently named “environmental melancholia”—a complex stew of feelings such as grief, anxiety, dread, remorse, helplessness, depression, fear, and other mental experiences sprung from the scientifically informed, almost dead certainty that humans have launched an ecological catastrophe the Earth can’t escape.

Mostly it’s scientists who suffer from environmental melancholia, but others, such as journalists who make it our job to find out what’s really happening, also do. It’s painful enough for me just to assemble these notes on the environment and its politics every couple of months. McKibben wrote the first book-length warning on climate change, The End of Nature, 30 years ago. Wallace-Wells started researching environmental news years ago as a global warming skeptic. After thousands of reports, studies, and interviews, he’s now a self-described “alarmist.”

The Nuclear Cantos were supposed to be a force of beauty depicting what could happen, in hopes it wouldn’t. The naturalist columns are about a disaster that’s already under way. My grandson is going to have to find a way to live through the beginning of the worst. This is excruciating.

Dana Wilde, a former editor, college professor and literary scholar, lives in Troy and writes the Backyard Naturalist column (www.centralmaine.com/news/dana-wilde-cm/) column for the centralmaine.com newspapers.