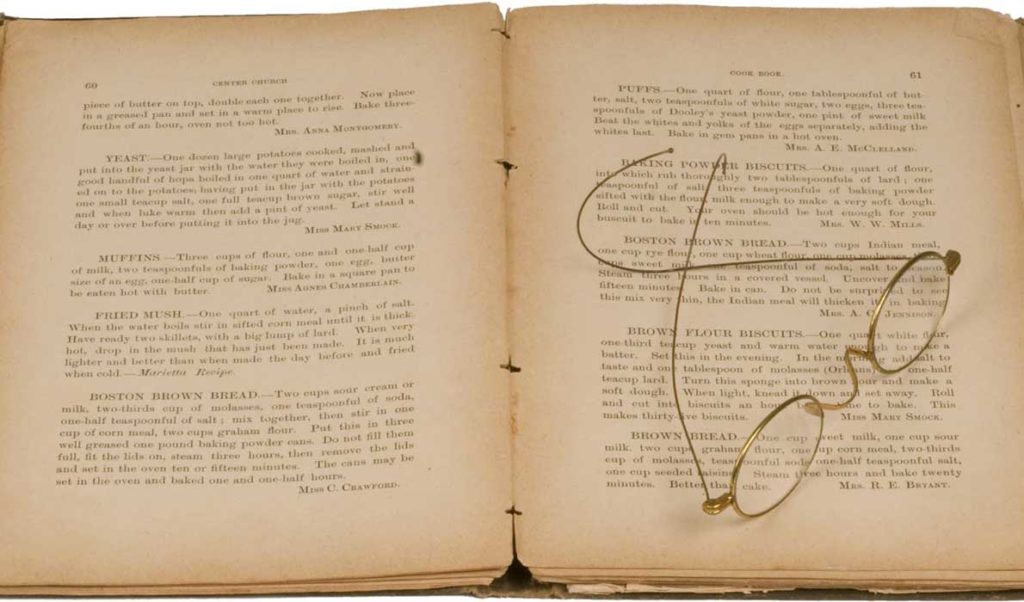

Sometime in the 1930s, the members of the Islesboro Women’s Club spent hours typing out recipes they collected from their membership and neighbors and assembled it into a cookbook that they covered with canvas. Embroidered on the front were the words “Cook Book” and a figure of what appears to be a baseball player. By some bit of good fortune, I ended up with two copies, one originally belonging to Leoda Hatch and the other to Martha Randlett.

The names attached to recipes inside include place and common family names here on-island: Pendleton, Hatch, Trim, Babbidge, Williams, Sprague, Gilkey, Boardman and Leach. Mostly, the ladies are identified by their married name, Mrs. Frederick Something or Other, Mrs. Sam, Mrs. Edwin, and so on; only the Miss Margarets and Miss Ruths survive with their given names.

All those women and their recipes: perfection salad, several chocolate cakes, chicken salad, scalloped clams, Thanksgiving pudding, salad dressing, lemon pie, doughnuts, potato puffs. I’ve tried some of the recipes and they are quite good.

Community cookbooks like this one, usually assembled for fundraising purposes, open a window into community life. All kinds of trends and fads show up. Perhaps a bit of competitive spirit: seven chocolate cakes going head-to-head? In any published cookbook like the battered Joy of Cooking on my book shelf, or yours, it is anyone’s guess how many of the recipes were ever actually used. But in community cookbooks, chances are very good that the recipes included are a fair representation of dishes truly tried and proven, possibly recruited from women known for their success with them. Living on in print like this is a kind of immortality.

I expect that any one of the Mrs. Pendletons or Mrs. Hatches did not need a community cookbook to add a friend’s recipe to her collection. She could have exchanged recipes over a cup of coffee in her own kitchen or swopped them in the church kitchen. Over my years of recipe research, I’ve seen lots of jotted recipes tucked or even pinned into women’s recipe collections, annotated with “Aunt Mary’s custard,” or “Harriet B’s chocolate cake.” New brides received as gifts fresh notebooks of useful recipes, clearly some family favorites with cousins, aunts and grandmothers identified as the recipe source.

Exchanging recipes is a centuries old practice pointing to curiosity, willingness to teach and learn, to share generously and to foster a bond between women over work they had in common: producing family meals day after day. We still do this, and nowdays, because some men do the family cooking, we share recipes with fellows we know, too.

It’s such a logical urge; we taste something at a friend’s house or at a potluck and observe that their result is better than the one we get; or is an intriguing new wrinkle; or solves a problem we have about not knowing what to do with some ingredient or other.

Some families make an effort to collect a mother’s favorites and turn them into small memorial notebooks passed out among children and grandchildren; some moms anticipate that desire and record family favorites, shared widely among kin.

When I cook from a friend’s recipe, I invariably recall them and the time we exchanged ideas. I’m old enough now to prize recipes from beloved friends and family no longer with us, or who live very far away. As long as I cook what they, too, cooked, as I think of them, they, too, have a kind of immortality with me.

Still, from time to time, I run into cooks who don’t share recipes, and I am always surprised and a little disappointed. I can’t tell you how many times people have said to me that they wished Auntie or Grandma had written down how they made that wonderful meatloaf or that cake they always ate at Christmas. Instead, the recipe went to the cook’s grave with her, and the family is bereft of more than just a person, because a favorite flavor and odor is gone, too.

Eventually, the maker is forgotten. That odd sort of proprietary urge guarantees oblivion. What a charming, even loving legacy it is to write down how to make that perfectly chewy ginger cookie or those exquisite chocolate caramels. Thank goodness for the generous spirits among us who, with their recipes, will be long-remembered.

Sandy Oliver is a food historian who cooks, write and lives on Islesboro.