On an overcast morning in June 1936, 23 young men scrambled into two brown trucks in Southwest Harbor and headed south. By midday, they arrived at a soggy field beside a fir grove on the outskirts of Camden. There, six Army trucks from Fort Williams in Portland were waiting, loaded with supplies and equipment. The men set to work unloading the trucks and “erecting sufficient canvas” to provide temporary shelter.

The cook dug a fire pit for his field range. A truck was sent to the Camden Fire Department to bring back water. The leader of the group, Army Reserve Capt. Herbert C. Pendergast, went to town and returned with a ham, one slice of which comprised each man’s first meal at camp.

The men were issued candles and mosquito netting. When they laid down on folding cots, propped on shims because of the slope of the hill, a cold fog rolled in from Penobscot Bay. It would rain for eight of the next nine days.

So began the 1130th Company of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Over the next six years, hundreds of CCC boys spent thousands of man-hours reworking the landscape—clearing undergrowth, building roads, trails, and structures, creating water and sewer systems—to create Camden Hills State Park. They did this work largely by hand; no power chain saws, only axes, hand saws, two-man crosscut saws, shovels, and pick axes.

More than 80 years after the CCC camp closed, many of the projects those men completed have been lost—there is nothing left of an ingenious timber bridge that used no nails, and a mile and a half of downhill ski trails have been reclaimed by nature. But key elements have endured, from the stone stairways on countless hiking trails to the elegant entry gate and gatehouse to the current park director’s quarters to Tanglewood Camp along the Ducktrap River.

The federal government had acquired 4,331 acres in Camden and Lincolnville for the “Camden Hills Mountain Park Project.”

According to a report in the Rockland Courier-Gazette, the 58 parcels purchased included “many poor farms which are unable to support their present owners.”

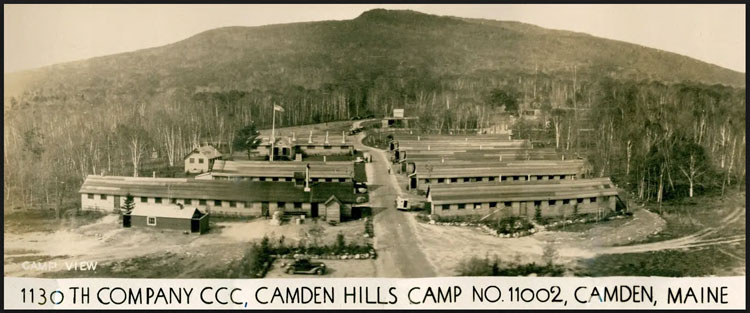

The CCC camp was located a mile north of Camden village off Route 1, on the site of the former Sagamore Dairy Farm, whose buildings had burned down years earlier.

Within weeks, the initial CCC cadre was augmented with reinforcements to help construct permanent camp buildings—four barracks, each housing 50 men, a laundry/bathroom, kitchen and mess hall, recreation building, infirmary, administrative building, officer housing, garages for trucks and equipment, repair shop, blacksmith shop, and tool building.

For the next six years, a steady complement of 200 men rotated through, toiling to carve a park out of the Camden Hills.

At 10:40 a.m. on Aug. 10, 167 new CCC enrollees stepped off a train at the Rockland railroad station. An hour later the group arrived in Camden and were soon having their first meal in the camp mess hall. For the next six years, a steady complement of 200 men rotated through, toiling to carve a park out of the Camden Hills.

Arguably one of the most successful Great Depression-era jobs programs, the Civilian Conservation Corp—sometimes called Roosevelt’s Tree Army—employed three million men in conservation-related work from 1933 to 1942.

One in four American workers was out of work at a time when most households relied on a single income. Bank closures, and home and farm foreclosures were sapping the economic vitality and morale of communities from coast to coast. People skipped meals, turned off their heat, and sometimes electricity as well, inserted cardboard scraps in holey shoes, and used paper from free shopping catalogs for toilet paper.

The prospect of three square meals and steady work was attractive to boys who were going hungry at home or, in some cases, had no place to call home. In fact, even among those who cleared the physical fitness bar, 75 percent of CCC enrollees entered underweight, many weak from malnutrition.

Snaring a spot as a CCC member was competitive. By 1939, only one in five applicants was selected. Enrollees had to be 18 to 25 years old, physically fit, unmarried, and unemployed. They were paid $30 a month, of which $25 was sent to their family. The CCC also provided spots for smaller numbers of out-of-work World War I veterans (no age or marriage restrictions), as well as so-called Local Experienced Men from the immediate community who could train the regular recruits in the skills needed to accomplish their work, such as handling an axe or forestry management.

In the April 1936 issue of The Sagamore, the Camden camp newsletter, the CCC was described as having “two fundamental objectives: the completion of worthwhile projects and the building of manhood … In the Civilian Conservation Corps camps many opportunities are given you that are not to be had on the outside: honest work, the chance to learn different jobs, religious, social, athletic and educational advantages—these are all here.”

In addition to stable employment, educational opportunities were a core component of the CCC. Most enrollees had no more than a high school education and thousands of boys learned to read and write thanks to the camp education programs. The Camden camp provided courses four evenings a week in practical subjects such as business, arithmetic, automatic grease gun operation, blacksmithing, English grammar, first aid, typewriting, diesel engines, etiquette, navigation, and auto mechanics. There were also less academic offerings: radio club, boxing club, bow and arrow making, fly fishing, orchestra.

Camden was one of 28 CCC camps in Maine, each with a complement of roughly 200 men, in addition to 50 “side camps” with 50 to 75 men. More than 16,000 Mainers found employment in the CCC. They worked on what became Acadia National Park, Baxter State Park, hundreds of miles of fire roads, dozens of fire towers, telephone lines, erosion control, water and sewer lines, tree planting, rip rap projects, and forest insect and disease control.

The 1130th Company in Camden worked under the direction of Hans Heistad, a gifted landscape architect who was the visionary behind the most iconic elements of the fledgling park. The stone park gate and gatehouse were Heistad’s design, as was a cascade and rock picnic area on the lower Sagamore section and the warming hut at the base of the ski trails on the east slope of Mt. Megunticook.

“We don’t disturb nature. We just improve on it,” Heistad told a Rockland Courier-Gazette interviewer. “We make a picture out of the material God has let us have.”

Company leaders submitted a comprehensive park master plan for approval by CCC authorities in Washington. Work progressed on a project-by-project basis, with detailed accounting of man-hours and materials expended on each aspect of the park’s construction.

Not everything in Heistad’s master plan was realized. The CCC never dammed several streams near Spring Brook Valley to create a fishpond. Nor did his most ambitious vision come to fruition: a 1,500-seat amphitheater carved into the hillside of the lower Sagamore section, appointed with stone terraces and overlooking Penobscot Bay to Islesboro, Vinalhaven, and North Haven.

The CCC crews built Tanglewood Camp on a 50-acre tract along the Ducktrap River in Lincolnville, including 40 rustic buildings with capacity for 72 campers plus staff, and an 80-by-120-foot swimming pool supplied by an artesian well.

In 1939, when the YWCA of Bangor and Brewer occupied it, the Bangor Daily News described Tanglewood Camp as “a modern recreational project built by the government as a demonstration of the best in architectural planning for a character-building camp.”

Today, the University of Maine Cooperative Extension operates a 4H camp there.

When they weren’t building picnic areas, scenic drives, hiking trails, camp sites, Adirondack-style shelters for use by overnight hikers, a fire lane around the 5,000-acre park property, or planting more than 7,000 trees and shrubs throughout the park, the men of the 1130th Company were put to work away from Camden. Fifty members worked for weeks-long stretches at a “side camp” near Katahdin, building the truck trail into Roaring Brook Campground in the recently created Baxter State Park. Camden CCC boys were called on to fight forest fires in nearby Lincolnville and as far away as Boothbay Harbor and assisted in search and rescue missions. On at least one occasion, they helped search for an escaped prisoner from the Thomaston prison.

While Americans generally supported the CCC, many residents were apprehensive about a camp being sited in their community.

Locals fretted about how 200 young men fresh off the breadlines and unaccustomed to discipline would behave when they ventured into the local community on a Saturday evening. But the record suggests a symbiotic relationship between Camden’s CCC boys and the host communities.

Camp leaders regularly emphasized the need for the boys to comport themselves in ways that would reflect well on the reputation of the camp. In March 1937, Commanding Officer Capt. M.D. McLaughlin wrote: “The boys of this camp have been well received by the inhabitants of Camden and have many friends there. They have entered social life, assisting social groups in putting on shows and so forth. Some of the enrollees have taught in church schools and have done other church work as well.”

At Christmas, CCC boys repaired toys for needy children. During the winter of 1940-41, CCC enrollees volunteered weekends to help with the construction of a ski jump and other elements of what is today the Camden Snow Bowl at Hosmer Pond.

In turn, Camden and Rockland schools loaned 3,000 textbooks for the camp library and education programs and enrollees had borrowing privileges at the Camden library.

Not only did men serving in the camp’s close quarters form lifelong friendships, more than a few men struck up romantic relationships with local girls that led to marriage.

Most of the senior leaders of the 1130th were commissioned officers or had military backgrounds. Some were veterans of “the World War” (in those years, few contemplated a second great global conflagration).

The Roosevelt administration explicitly fashioned the effort as a civilian undertaking, resisting voices advocating a more military flavor. As the years passed, some questioned that approach. By 1936, some members of Congress proposed giving CCC boys limited military training and weapons familiarization. Three years later, 75 percent of respondents to a Gallop survey thought that “military training should be part of the duties of the boys in the CCC camps.”

While no such change was ever implemented, CCC enrollees nevertheless benefitted from military discipline.

“All aspects of our lives as CCC boys were Army-oriented,” wrote Norman Wetherington of the 1124th Company in Bridgton. “We lived by Army regulations and ate Army chow. Our clothing, equipment, and inspections were Army, much of which was World War I vintage. The one exception to regulations was that we did not have to salute our officers. We were a civilian organization.”

The U.S. officially entered the war on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. CCC camps across the country were closing because the men were needed in uniform. Ultimately, the training and physical fitness of CCC men qualified them for quick acceptance into the armed forces and 90 percent went on to serve.

On Aug. 8, 1941, the Camden Herald carried a three-paragraph item at the bottom of page 2 reporting that the 1130th Company had left town. By then, only 78 men were still at the camp; 48 transferred to Bar Harbor and 30 to the camp in Alfred. As CCC members went to war, the Camden camp became home to an army detachment.

The 1130th Company “successfully carved a ‘park’ out of land that had been lumbered, burned over, and neglected,” recalled Earlyn W. “Stubbie” Wheeler of Rockport, a foreman at the camp. “It left its mark on the community and on the hundreds of enrollees that came and went during its existence.”

Nationwide, the CCC instilled in thousands of men a deep appreciation for conservation goals and principles, values they shared with their families and communities.

The state of Maine took over management of the Camden Hills State Park in 1947.