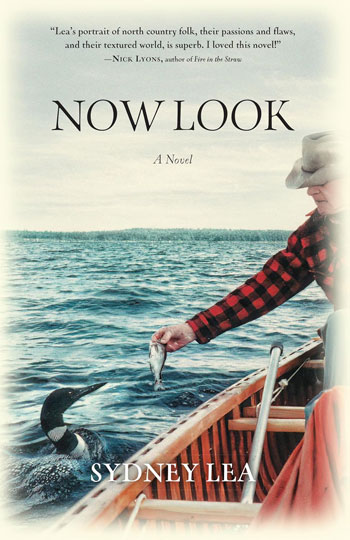

Now Look

By Sidney Lea, Down East Books

In an interview last year with Vermont Public Radio, novelist, poet, and essayist Sydney Lea shared with Mikaela Lefrak that he had been “at the business of recovery for a long, long time,” adding, “I’m blessed in that respect. Many people don’t get the chance.”

Drawing on personal experience, Lea has written a novel about a man, George Mayes, dealing with major demons of the alcohol kind.

George is a Yale graduate who spent his college years and after drinking everything in sight. Later, as the owner of Mayes Transportation, while tending a “sprawling garden of jonquil-colored school buses,” he routinely drives a route in an inebriated state, risking the lives of his young passengers. Looking back on these days, George beats up on himself in his attempt at self-realization.

Lea describes George as a “man for prayer, though it’s largely wordless and entirely creedless.” He has always longed to make his life “a coherent package.” To him, “Story just matters, period.” George “can’t come to grips with experience if he can’t tell it”—an assertion that might echo the author’s position.

Mayes is a Yale graduate who spent his college years and after drinking everything in sight.

As a devoted outdoorsman and a longtime visitor to Grand Lake Stream, Lea is especially skilled at limning life in the woods; he’s a descendant of Hemingway and his Nick Adams stories in that regard.

Describing a canoe trip on Semnic Lake with his friend Evan Butcher, he remembers the older man, his mentor, seated in the stern of the canoe, “a loon swimming close enough to take a mud chub from his hand,” an image that matches the photograph on the book’s cover.

Like Michael Connelly’s Bosch, George has a deep appreciation for jazz. Thinking of The Gerry Mulligan Songbook, he waxes lyric: “Goddamn good album, not a piano on the whole thing, completely different kettle of fish.”

George does most of the narrating, but Lea lets other characters take a chapter here and there to add perspective on the story. Among the most striking: the soliloquy of the man who murdered his parents and a short letter written from Vietnam by his friends Evan and Mattie’s son Tommy.

George is raised by great uncle Emory Unger and his housemaid, Mary Conley, who turns out to be among the most endearing characters in the story, making the boy is favorite sandwich, peanut butter and tomato, every Sunday.

“If heaven isn’t like that,” he tells his wife Julie, “I’ll boycott the place.”

Lea is brilliant storyteller in both prose and verse (he was Vermont’s poet laureate). His descriptive prowess is evident on every page. Here’s an account of a river driver who has been fished out of the river. “Evan spoke of how they poured a carton of salt into his bedroll and wrapped him in it. ‘Like corning venison,’ as he once put it, sad-eyed, ‘and salt were dear.’”

At one point, George muses, “reminiscence can be a sickness, just like the bottle,” yet he holds on to memories as tightly as he once held onto a fifth of vodka. He finds it strange how so often “the episodes in a person’s life that lodge themselves in the mind are not necessarily important ones: fizz of a soft drink; lower hiss of a river fifty yards away; Evan’s old hound bawling in his pen.” Like George, Lea is “someone remembering someone remembering”—and we listen in with wonder and sympathy.

Carl Little lives on Mount Desert Island. His latest poetry collection is The Blanket of Night.