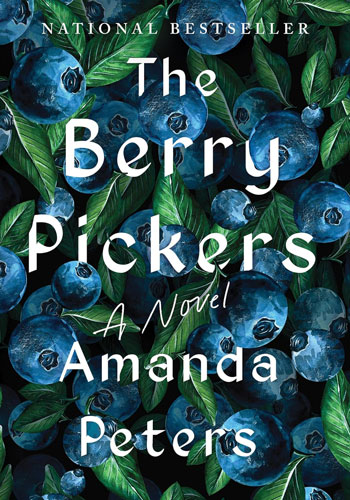

The Berry Pickers

By Amanda Peters (Catapault, 2023)

Amanda Peters has Mi’kmaq and settler ancestry and lives in the Annapolis Valley of Nova Scotia. She was winner in 2021 of an Indigenous Voices Award. The Berry Pickers was her first published book (2023), with a book of short stories just out.

Peters has set this book in both Nova Scotia and in Maine’s blueberry fields. The story focuses on a Canadian Mi’kmaq family, told by a brother and sister. All five children, with their parents, go to Maine every year in late July for the harvest of blueberries and then potatoes.

This migrant labor is not uncommon and is shared with other Indigenous Canadian families like them, and the American farmers who hire them provide some rooms and outdoor space for camping as living quarters. Peters’ own grandparents were berry pickers and she grew up hearing their stories.

Canadian Indigenous children were still being taken from their families and sent to boarding schools in the early 1960s, the setting of the novel. The government’s goal, as in the U.S., was to erase Native language, history, traditions, and identity.

In this family, the two oldest children were sent to boarding school but allowed to rejoin the family during summers while they worked. Eventually they were withdrawn from the school by the parents to live at home, after their father grew irate about the implication that without proper institutional guidance, Indigenous children otherwise grew up lazy and unproductive. (A note here about language: Peters uses “Indian” and not “Indigenous” or “First Nation,” perhaps more in keeping with the time period portrayed, when “Indian” was commonly used.)

The story kicks off when the family is in Maine harvesting berries, and the youngest, Ruthie, 4 years old, goes missing. The reader is as baffled as the family. But then a new narrator, Norma, is added.

We’re given lots of clues that Ruthie and Norma are the same little girl, although their circumstances couldn’t be more different. Norma’s “mother” is a depressed white woman, married but childless. The book’s male narrator, Joe, Ruthie’s older brother, believes he was the last to see her near the fields. He feels guilty, blaming himself for failing to keep her safe.

As the story progresses, Norma grows up impacted by her mother’s secretive behaviors and sometimes weak explanations of Norma’s past. Norma has dreams and vague memories that seem to indicate a past that differs with her mother’s version.

We can see how her American mother’s depression and anxiety, the sense of secrets, as well as the power of Norma’s dreams and memories create nagging questions and insecurity, persisting into adulthood.

I was interested to see in The Berry Pickers an example of what I had recently been drawn to while reading Percival Everett’s James, a retelling of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, but with Jim/James as the narrator. James and other enslaved blacks are shown as fully developed characters with emotions and intellect, who have figured out the benefits of acting the part assigned to them by ignorant whites.

In The Berry Pickers, Peters includes a chapter where Ruthie and Joe’s “Injun” father takes white men out on hunting excursions and is very aware of the stereotypes whites hold. He plays to these knowingly, correctly anticipating that providing an authentic “Indian guide” will give the hunters what they hoped for, with a large tip in it for him.

The Berry Pickers touches on threads readers can learn from, including the impact of trauma; the value of dreams, journaling, and therapy; and the poor treatment laborers and people of color can receive.

I think Peters’ writing makes this book accessible to adolescent readers as well as adults, as a history lesson from the not-too-distant past.

Tina Cohen is a therapist who spends part of the year on Vinalhaven.