In the summer of 1953, Indiana-born, New York City-based painter Stephen Pace (1918-2010) made his first trip to Maine. On that fateful tour, Pace and two artist friends spent a month on Monhegan and then headed north and east to further explore.

As art historian Martica Sawin relates in her monograph Stephen Pace (2004), “on a whim [they] turned onto a road that led down a long peninsula to terminate in a bridge to Deer Isle.”

Camping on the shore near Stonington, Pace, like John Marin, William Kienbusch, the Zorachs, Siri Beckman, Jill Hoy, and so many other artists before and after him, fell in love with the place. After many summer visits, in 1973 he and his wife Palmina purchased a yellow farmhouse, their home in Maine.

Faced with a vibrant island world, this celebrated abstract expressionist shifted his sights from inner visions to coastal subjects without losing the drive of his previous work. Wielding a wide and swift brush, Pace captured Stonington scenes with gestural bravado, the paint seemingly swept across the surface.

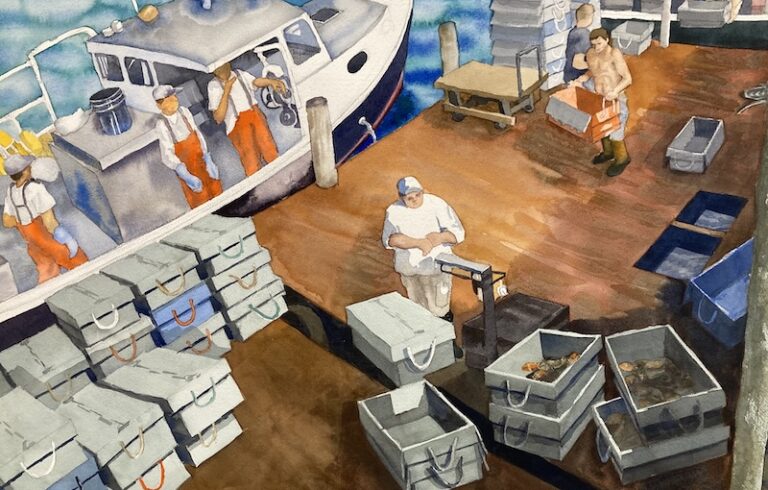

Pace frequented the town’s working waterfront in search of subjects. He focused on the lobstermen engaged in their daily tasks: moving lobster gear, unloading at Duryea’s pier, setting out for the day. He also painted lobstermen at sea, hauling traps and banding lobsters, and clammers bent to their work on nearby mud flats.

“Loading Bait No. 6” captures the action at the Stonington co-op. Two men, one in the door of the bait shed, the other standing on the deck of his boat, maneuver a wide basket that hangs in mid-air. The boat’s white stay sail, or spanker, slices up through the painting. This triangular piece of canvas, which keeps the boat headed into the wind and helps reduce rolling in waves, adds a dynamic element to the composition.

Pace’s palette and brushwork display a freedom that nonetheless represents reality.

“He has watched his fisherman and clam digger neighbors go through the familiar motions of their work so many times,” Sawin observed, “that he can with seeming ease set down the essence of a gesture or stance with a few strokes of his brush.” His paintings, she concluded, are “essentially a celebration of visual pleasure.”

The couple’s legacy to Maine is remarkable. They donated their beloved Stonington home to the Maine College of Art and Design, which uses it for artist residencies. Fryeburg Academy named its art space the Stephen and Palmina Pace Gallery.

And a foundation bearing their names, established in 2016, “promotes art as a cultural necessity through the support of working artists and educational programs.”

Pace’s remarkable paintings underpin all those generous gifts to the future. That this painter, born and raised in the Midwest, came to chronicle one of Maine’s busiest waterfronts is something of a wonder—and one more testimonial to the appeal of the coast to artists from everywhere.

More of Stephen Pace’s work can be found at the Dowling Walsh Gallery, which represents his estate. He is the subject of the documentary Stephen Pace: Maine Master.