In early June, conservation patrol officers with Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans were on a patrol flight in an area known as the Sackville Spur, about 310 miles east of Newfoundland’s coast, when they spotted a North Atlantic right whale, identified as Eternity, swimming with a group of pilot whales in a location where right whales normally aren’t.

The officers were surprised to see the endangered whale there, but the scientists working in the Tandy Center for Ocean Forecasting at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay were not—because they’d predicted it.

“Where exactly did that whale occur?” asked postdoctoral scientist Jonathan Syme. “It was right there on that little bit of blue in this area that we predicted would become right whale habitat,” he said as he pointed to a slide projected above his head in the forum space of the newly opened Harold Alfond Center for Ocean Education and Innovation at Bigelow.

Syme, along with postdoctoral scientist Rebekah Shunmugapandi and senior research scientist Nick Record, presented the first lecture of Bigelow’s annual summer lecture series, Café Sci.

“When we know where the food is, we’ll be able to predict where the right whales are likely to be.”

Held July 16, their presentation shared some of the science-based modeling and forecasting tools scientists at Bigelow are using to predict where and when North Atlantic right whales may show up in the short-term and the long-term.

With the current disagreement about regulations to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whale—of which there are an estimated 350—“there’s a really important role for science to play,” said Record, director of ecosystem modeling at Bigelow’s Tandy Center, “when these different approaches to management start to crack and fall apart.”

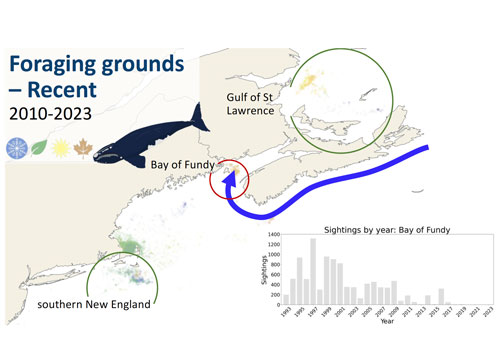

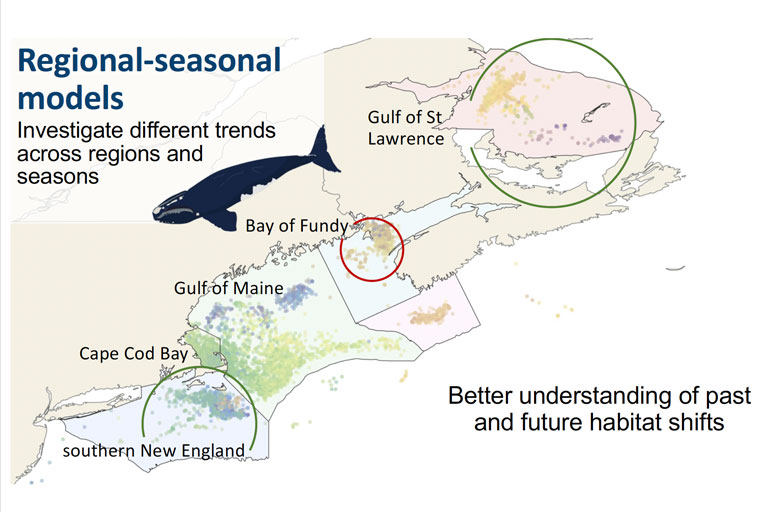

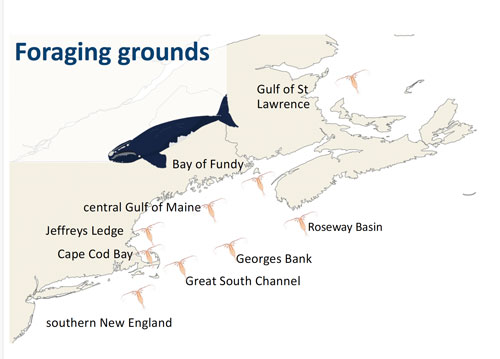

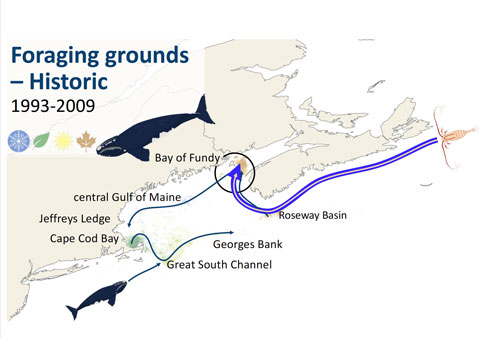

To make the long-range forecast that pinpointed the Sackville Spur as a place right whales would eventually go to in the next five to 20 years, Bigelow scientists used prey data and regional and seasonal right whale movement data along with parameters such as water depth, temperature and salinity from 1990 to 2015.

The modeling using this data predicted which historical foraging areas would be maintained, and which would not, and which areas right whales would go to in the future, including the Sackville Spur area.

“Just like you have a weather forecast that says what the probability of rain or clouds or sun is in the next few days, we can make maps that tell what is the probability of whale occurrence in the coming days, and these maps could be used by researchers and management and fisheries to inform their decisions,” Syme said.

Bigelow scientists are also working on incorporating real-time data from satellites into their models, Shunmugapandi said.

“We want to use the remote sensing methods to detect whale food,” she said. “When we know where the food is, we’ll be able to predict where the right whales are likely to be.”

The places North Atlantic right whales are foraging are shifting because the changing climate alters ocean currents, the scientists said, which in turn affects where whale food will show up. Being able to more easily determine where North Atlantic right whales are going to go ahead of time is crucial for both the whales’ survival and for the industries that are most affected by regulations to protect the whales.

“One of the things that we’re hoping these forecasts can do,” said Record, “is help get a heads up before whales show up in large numbers in an area so that we can have some planning in terms of what we do.”

To watch the lectures of the Café Sci series, go to Bigelow’s YouTube channel.