The Boat School is riding a wave of momentum as the Eastport-based institution nears the completion of the first of six steps in its revival. The famed school, which opened in Calais in 1969 before moving to Lubec in 1971 and settling in Eastport in 1978, could reopen as the Maine Marine Technology Center within the next few years if supporters have their way.

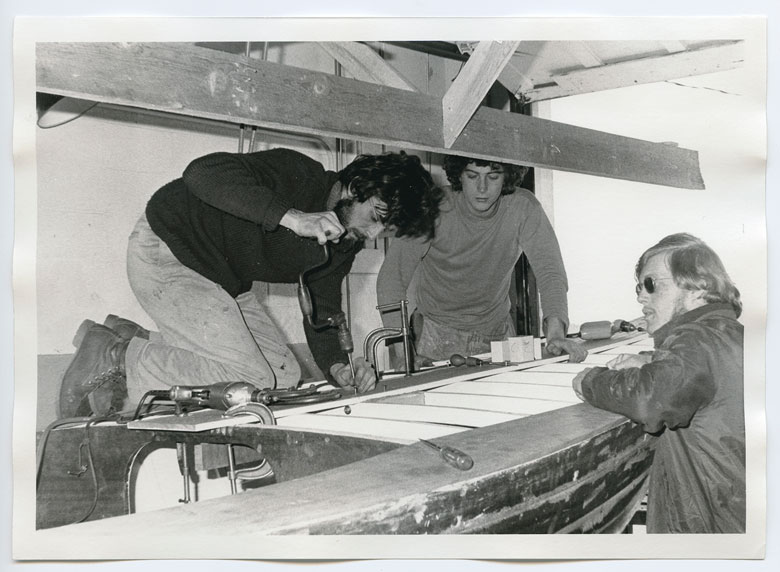

Since its earliest years, the Boat School has been a lifeline for students involved in boatbuilding and its various associated industries.

For Dean Pike, who was born in Lubec, it was a way to stay in the area when aquaculture was still in a fledgling phase.

“I had marine biology at heart, and had to figure out how to make a living in Washington County,” he recalled. Then he realized “every aquaculturist, every fisherman—they need a boat. The Boat School seemed like an obvious choice.”

“There are so many trades involved in building a boat and maintaining a boat.”

—Dean Pike

Pike enrolled at the Boat School in 1978 and graduated in 1980. The same year, he finished building his first house—and opened Moose Island Marine, a supply store that started business just in time for the unloading of freight to kick off at the nearby breakwater.

The Boat School gave him a foundation for everything he needed to know, including significant portions of building his house.

“There’s so much to learn. Boat building involves being a carpenter, a composition technician, a plumber, an electrician, a mechanic, a rigger, a painter,” Pike said. “There are so many trades involved in building a boat and maintaining a boat.”

Soon after graduating, Pike was approached by Boat School Director Junior Miller to teach when former instructor Clint Tuttle developed a wood allergy. He continued teaching there until the school closed in 2012 while under Husson University’s authority in what remains a controversial decision in the community. During Pike’s time with the school he taught hundreds of students from all over the world in courses ranging from marine surveying to joinery.

Among those Pike taught is Matt LaCasse, who enrolled at the Boat School in 2002 after graduating from Calais High School. He took courses in wooden and composite boatbuilding, marine systems, boat design, and electrical and mechanical systems, and built a 15-foot Whitehall rowboat in his first year and a 19-foot cold molded skiff in his second year.

“My instructors were extremely knowledgeable and took their jobs very seriously,” LaCasse said. “We worked and studied hard from sunup to sundown every day. My classmates and I were excited and proud to be diving into the world of Maine boats, the communities and social circles therein.” It was a fitting combination, and LaCasse “enjoyed it so much that I never left.”

When Pike sold Moose Island Marine, LaCasse bought it and renamed it Moose Island Marine Supply. He now operates it alongside its parent company, Eastport-based Deep Cove Marine Services.

For Bret Blanchard, who was involved in the behind-the-scenes work of the school’s chaotic early years and then through to its closure under Husson, restoring the Boat School would be restoring a historic Maine institution. In part through his guidance, the Boat School’s advisory committee developed an associate of applied science in marine technology degree, being among the first of the AAS degrees awarded under its then-parent school, Washington County Technical College.

“For my work on the project I won a few awards,” Blanchard says, “but what we really won was proving hands-on, dirty trades could award AAS degrees.”

Crediting the school with helping him find his “life’s passion” as a teacher in the marine trades, Blanchard is one of over a thousand alumni of the school, many of whom are keenly interested in seeing the school’s return. A handful, known as the Friends of the Boat School, are steering the course toward a $4.2 million restoration project, with the first phase—remediating the water-damaged buildings—to be completed by August.

To fund the first phase, the Friends won a $675,000 grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and a $120,000 grant from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, both of which enabled the replacement of the main building’s roof and asbestos removal, work that began in late spring.

Next will come infrastructure updates, followed by the acquisition of equipment, fixtures, and furnishings. It’s admittedly a long road ahead, but it’s difficult to doubt the sincerity of the school’s supporters.

While the school’s original draw was wooden boatbuilding, “We have to expand it,” Pike says. Along with incorporating traditional components, the new curriculum would focus on developing its composite education and composite design and construction offerings, tying into everything from aircraft to automobiles.

“It’s all about transportation,” Pike says of the field. “It’s all about moving people and products.” Other new components could be marine upholstery and welding, both of which have wide application.

Provided the Boat School meets its funding goal, enrollment expectations are straightforward enough. It could sustain itself with 50 students paying between $20,000 and $30,000 a year, Pike said. During its peak, the school hosted 100 students. If it were to reopen, it would be the third post-secondary school currently operating in Washington County.

“The Boat School is Eastport,” Pike said, looking out at Passamaquoddy Bay from a table at Horn Run Brewing. “Anybody that sits here and thinks we shouldn’t have it—I scratch my head.”