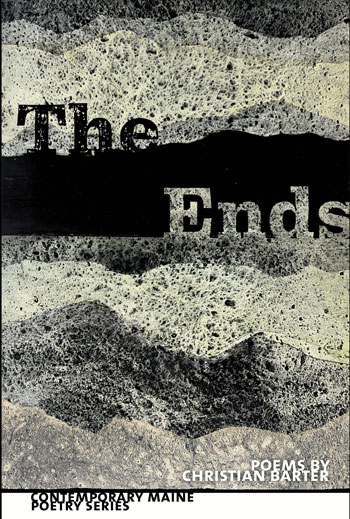

The Ends: Poems by Christian Barter

Littoral Books (2025)

One of the principal strands of American poetry since World War II was at first called “confessional,” because some poets began disclosing their own lives and traumas in unprecedented ways. The level of personal detail got pretty grueling sometimes.

The material soon expanded into further themes, including race, class, gender, art, language, and nature, among others. But the emphasis on what those things mean personally remained.

The poems in Christian Barter’s most recent poetry collection, The Ends, derive mainly from strands of confessional poetry processed through the MFA programs of the past about 60 years.

Confessional poets are not usually confessing anything, but more accurately, using their own private emotions, events, and relationships…

The term “confessional” was first used of poets such as Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton, but it has long since been deemed inaccurate. It was quickly recognized that confessional poets are not usually confessing anything, but more accurately, using their own private emotions, events, and relationships as the subject matter.

And this is the gist of The Ends.

The collection is presented in three sections. The first, “That In Black Ink,” comprises four wistful recollections of (apparently) the poet’s own growing-up years. “Elegy for Michael B.” is addressed to a high school friend who lived like a typical, rough, alienated, wild teenager and died young. Very personal

stuff.

The second section, “The End,” magnifies the personal thread into 34 “sonnets” addressed mainly to “Mariah.” They cover from different angles and complications the speaker’s wistful longing for her to come live with him on Mount Desert Island, even though he seems aware this could easily be the worst idea he’s ever had.

I’m telling you all this because you may

at some point come up here to live with me.

I’m asking you to. I’m writing you a letter.

I’m no longer interested in misdirection,

fragmented narratives, deconstruction,

lit-crit mantras that nothing means anything.

In these lines opens an emotional motif of the book: the futility he’s feeling, after apparently years spent working the MFA poetry circuits, about writing poems that will be paid attention to. We begin to feel this is truly “confessional” poetry after all, as he doubts the value of what he’s done and repeatedly laments his inability to write anything at all.

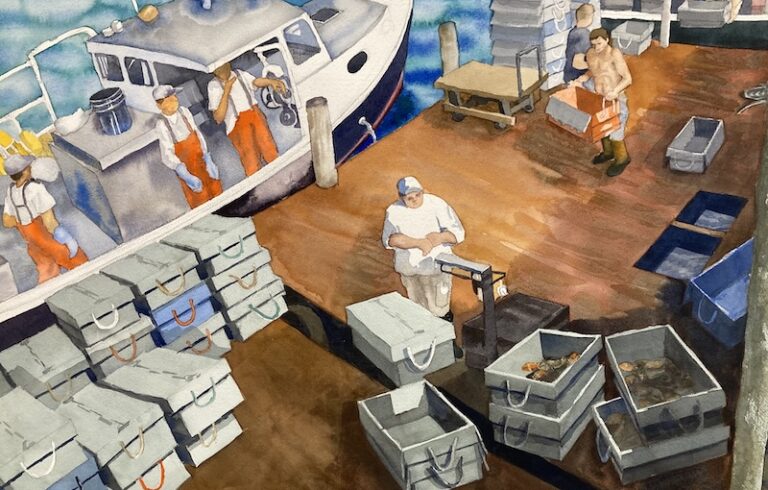

There are a lot of clues about why Mariah seems hesitant to move in. Barter’s longtime day job has been as a jack-of-all-trades for the National Park Service in Acadia, and most of the poems in the third section, “The Design Is Proof,” touch down there.

The main threads are poetry- and art-making and the coming ravages of climate change. As in the earlier sections, these thoughts are given in an air of wistfulness and futility.

He imagines Champlain sailing into Somes Sound for the first time, compares what the explorer saw to what park tourists see, and wonders with ambivalence if everybody feels the same religious awe he gets

in the vistas.

“Derrida” reflects obliquely on the psychic schism he feels between his academic/poetic life and the earth and water of Acadia itself.

The book’s most affecting moments involve his appreciation of the natural beauty there. The occasional poem “Acadia” chants, “May we trust what we feel when we are here.”

In “So Far” is one of the loveliest depictions of Maine autumn anywhere:

… here we are in fall again,

the oak trees dutifully unleaving,

the dense trail blanketed

and reeking of the life

that was, fermenting

so sweetly it almost smells

like spring.

Beautiful. And it’s couched in the wistful acknowledgment that climate change is about to undo everything. Even the universalizing themes involving beauty and climate change are given intensely personally.

Stuffed among the Acadia-nature expressions is the poem “Reading Myself: after Robert Lowell,” which seems like an effort to sum up the many problematic life-threads that have beset the poet.

We don’t create the world we envision.

We don’t become the world we’d like to see.

The writing that turned out the way I’d planned

wasn’t poetry.

The Ends is a book that attendees of poetry workshops of recent decades will prize, I imagine, for its heartfelt willingness to try and grapple, in a very personal way, with some of the workshops’ most recognizable themes.

Dana Wilde is a former college professor and newspaper editor. He lives in Troy.