For generations, the lobster fishery has been a cornerstone of Maine’s economy and a defining element of its cultural identity. Lobstering is a tradition deeply woven into the fabric of coastal communities. Yet the story of how lobster became a widely consumed product is not just about flavor, but also an era of innovation and industrialization.

In the early days of the commercial lobster fishery, the market was limited due to the crustacean’s highly perishable nature. Unlike cod and other finfish, lobster meat could not be dried, salted, or smoked in a way that preserved its flavor and texture. This made long-distance transport and storage difficult, restricting lobster’s reach outside of local markets.

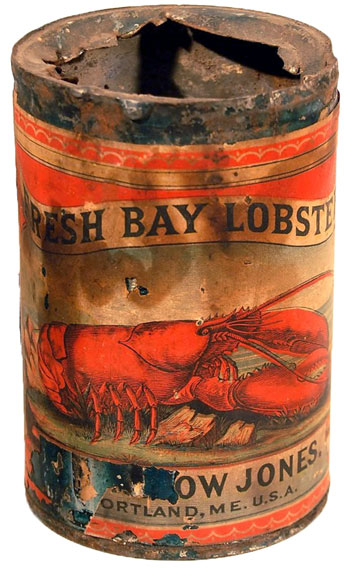

To extend the shelf life of live lobsters, vessels known as “smacks” were outfitted with wells—essentially onboard tanks that allowed access to fresh seawater to keep the lobsters alive. This innovation enabled distribution to urban centers across the Northeast. However, the breakthrough that truly brought lobster to a wider audience was canning. Lobster became one of the first foods to be commercially canned in the United States, transforming it from a regional delicacy into a global commodity.

Men handled the heavy lifting and soldering of cans, while women cooked, processed, and packed the meat in addition to labeling cans.

By 1840, lobster canning had become established, though it wasn’t until decades later that the scale of the industry became clear. In 1880, Maine was home to 23 lobster canneries employing around 800 workers. Ten of these factories focused exclusively on lobster. Together, they produced 1.8 million cans in various sizes—half of which were exported overseas. That year, lobster landings totaled 14.2 million pounds, with two-thirds going to canneries. In effect, demand for canned lobster doubled that of the live market.

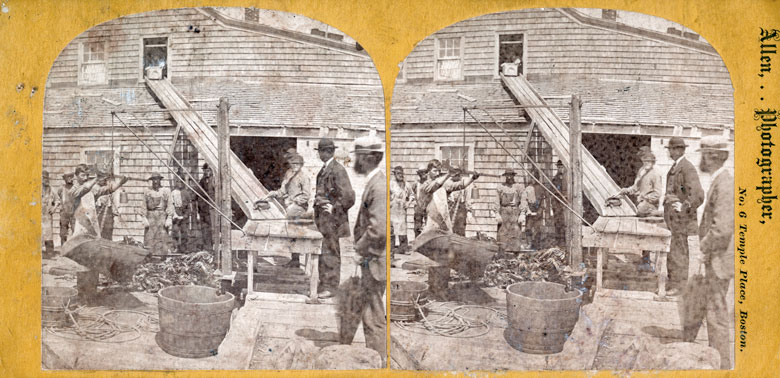

The peak of the lobster canning era is believed to have occurred around 1870, coinciding with the date of this image of the William Underwood Co. factory, which operated in Southwest Harbor at Clark’s Point. This cannery was established in 1860 and was forced to relocate to Bass Harbor in 1886. Its presence at Steamboat Wharf proved unpopular with ever-increasing tourists, who were greeted by the factory’s unpleasant odor upon arrival. Today, the site is home to a U.S. Coast Guard station.

Although this photograph shows only men, the workforce was predominantly female. Men handled the heavy lifting and soldering of cans, while women cooked, processed, and packed the meat in addition to labeling cans. Some of the men pictured may have been lobstermen unloading their catch from a schooner just out of frame.

Consumer demands for canned lobster drove increased harvests, sparking concerns about the sustainability of the fishery. In response, regulations began in 1879, including laws that restricted the canning season. As the largest lobsters were depleted, more effort was required to catch and process smaller ones, reducing profitability. Meanwhile, improvements in shipping—particularly the use of ice—made live lobsters more viable for transport, boosting their popularity. These factors led to the decline of lobster canneries in Maine, which had disappeared entirely by 1895, marking the end of a brief but transformative chapter in the lobster fishery. Shifting to other preserved seafood products, Maine canneries continued to thrive well into the 20th century.

Kelly Page is Curator of Collections at Maine Maritime Museum. The museum’s latest exhibit, Re|Sounding, explores under-told stories of Black and Indigenous contributions to maritime heritage. Explore resources and plan your visit at www.mainemaritimemuseum.org