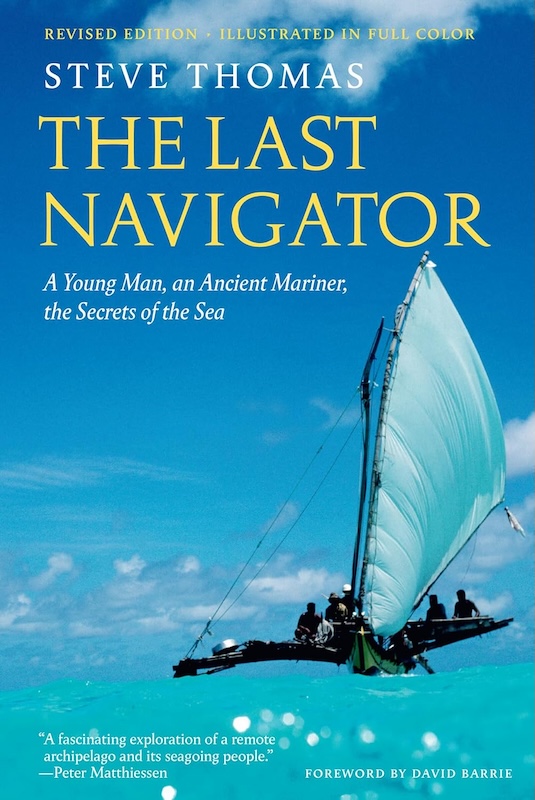

The Last Navigator: A Young Man, An Ancient Mariner, The Secrets of the Sea

By Steve Thomas (Revised Edition, The Abbeville Press, 2023)

I’ve never met Steve Thomas, but we’ve shared a lot: time in Micronesia (where his story takes place and I spent two years in the Peace Corps); an interest in sailing and navigation; and love of a good yarn, told in the presence of friends and a few drinks.

Steve’s time in Micronesia was some 15 years after mine—I joined the first cadre of Peace Corps Volunteers in the fall of 1966 to teach school on the island of Yap in the Western Carolines, while he went to Satawal (to the east of Yap but still part of the Carolines) in the 1980s as a researcher, journalist, and author studying traditional Micronesian navigation. I arrived with a college education and a smattering of its local language learned during Peace Corps training in Florida; he set out with a deep knowledge of ocean voyaging in the Atlantic and Pacific.

Both of us, as it turned out, had lots to learn.

A little history: Micronesia, an array of islands stretching from Guam and Palau on the west to Ponape, Truk, and the Marshalls on the east, are perhaps best known as Pacific dots where World War II was fought. Many were colonized by Spain, then Germany, then Japan before falling into U.S. hands after the war under a U.N. trusteeship. Yap had hosted a communications station and a Japanese airfield. Truk was the site of a large Japanese naval base. Atolls in the Marshall Islands became atomic testing sites. Over the years occupiers—both missionaries and military—engaged with islanders in many ways, from schools to fisheries, from churches to slave-labor camps. The Micronesians Thomas and I got to know may have seemed isolated to us, but in fact they’d been part of a huge, centuries-long drama of colonization and war.

Traditional Micronesian navigation—the central topic of this book—is based on readings of stars and ocean swells, from shore and from canoes in the open water. Compass, clock, and sextant, the three basics of Western navigation, were unknown to Micronesian mariners, but that didn’t keep them from attempting ever-longer ocean voyages. The systems developed by Yapese, Trukese, Marshallese, and other Micronesian and Polynesian navigators, Thomas writes, satisfy “the three basic requirements of any navigational system: to determine the course to an objective, to maintain that course at sea, and to measure and compensate for the displacement from the correct course by current or other factors such as leeway and storm drift.”

Unlike Western systems such as LORAN, GPS, or sextant and compass, Micronesian navigation eschews charts or instruments. “It relies on a vast body of lore and the navigator’s own senses,” Thomas writes. A navigator knows the course to his destination, “the star under which the island lies—at night he maintains his course by following that star… if it has not yet risen or is too high to steer by, he selects one of a number of substitute stars that travel the same arc or path through the heavens…. The student learns them from his master over years of apprenticeship.”

If anyone on Yap—where fishermen eventually shifted from canoes to wooden or fiberglass boats powered by outboard motors—carried even part of such knowledge in his brain, no one told me about it. Boats carried compasses or didn’t venture far offshore; if you wanted to get to one of the outer islands in the 1970s, you took the mailboat or flew. Traditional navigation was historical lore, little more.

Thomas, however, spent most of his Micronesian time on one of the Yap District’s most distant—and traditional—islands, Satawal, where the mailboat went once a month. Traditions were stronger, even at the time he was there, some 15 years after I lived on Yap.

Islands anywhere can be places of magic and secrets. On Yap in the 1960s I got to know a “magic man” who could make it rain: show him how much water you needed to fill your catchment or tank and when (“tomorrow or the next day,” you were supposed to tell him), ask him politely, and give him a small gift (preferably a bottle of Japanese whiskey). We did those things and stood by, not forgetting tales of a typhoon that had struck Yap when the U.S. Navy had presented its chosen weather man with a whole case of whiskey. On schedule, it rained and our tanks filled to the brim. In the 1960s at least, Yapese weather magic was still potent and believable.

Fifteen years later, in the face of clannish and chiefly jealousy and secrecy surrounding traditional navigation, Thomas earns enough of some islanders’ trust to apprentice himself to one or more navigators. He learns at least some of their secrets and even travels with them aboard breadfruit-wood outriggers to islands even more remote than Satawal. The navigation he saw and learned about may not have been as “magical” as what I experienced—it was based on generations of observations and practice—but much of it was off-limits to most outsiders. Penetrating that secrecy was the key to writing this book, the second (revised and well-illustrated) edition of which I’ve now read. I spent years as a journalist, and I know good journalism when I see it.

From the Phoenicians to the present, navigation has evolved, developing—often in secret—around human needs for everything from fish to treasure. Medieval Portuguese fished the grounds off Newfoundland for years without revealing how they got there and made fortunes in the process; Englishmen and other Europeans puzzled over longitude centuries before discovering the virtues of an accurate clock for that purpose; ancient Chinese contributed the magnetic compass. More modern times have given us LORAN (a tall tower was built on Yap to send its signals to aircraft and Navy ships); Satellite Navigation (SatNav) and the Global Positioning System or GPS.

The navigation story will always be a global one, rich with secrets and surprises, and Micronesian navigation is an important part of that story. Steve Thomas’ exploration and telling are real contributions to it.

David D. Platt is former editor of The Working Waterfront.