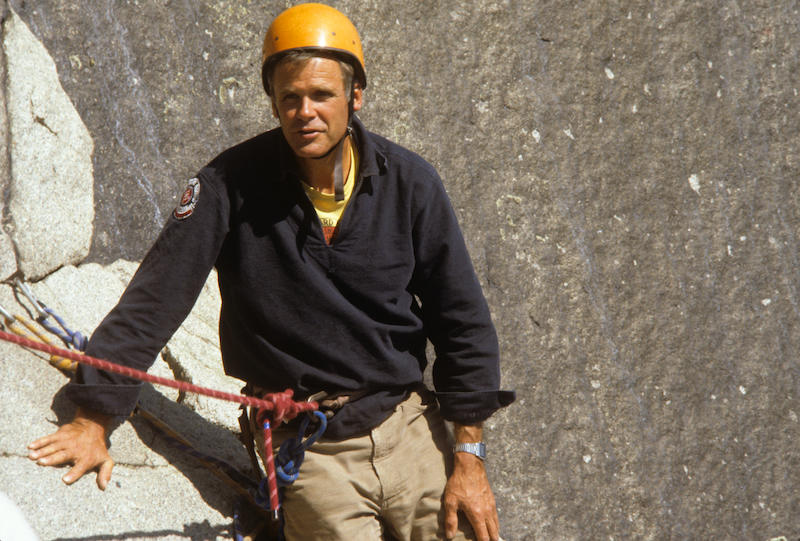

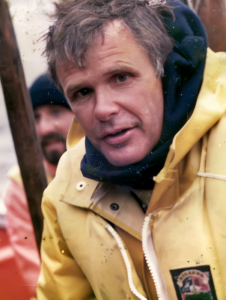

Most people clearly remember the first time they met Peter Willauer. I certainly do. An imposing 6-foot-2-inch figure, Willauer looked like he walked out of the movie Captains Courageous. A former Naval ensign and sail training instructor at the U.S. Naval Academy, Willauer was a consummate heavy weather, small boat sailor. He also had another side to round his charismatic presence—a romantic nature, perhaps passed down from his great uncle, Winslow Homer of Prouts Neck, where Willauer spent summers a stone’s throw from the artist’s historic studio on the shore.

In the early 1960s, Willauer might have struck people as heeding John F. Kennedy’s call asking people like him what he could do for his country. Willauer’s answer was to lead an organization that sought to bring a British Outward Bound-type sea school to the East Coast of America. Willauer had been introduced to the educational philosophy of Kurt Hahn, a German refugee who had gained international renown for teaching survival skills to merchant seamen in a program that had saved thousands of lives during World War II. Hahn’s program for teaching survival skills had been honed at the Gordonstoun School on the North Sea coast of Scotland, which had educated young men, including Prince Philip and later Philip’s son Charles in the character-building traits of self-reliance, compassion, and sensible self-denial.

In 1963, Willauer, with his gutsy seagoing wife, Betty, landed on the shores of Hurricane Island in Penobscot Bay because he had heard it had everything he would need to found an Outward Bound sea school. Hurricane Island offered cliffs for climbing, a freshwater quarry for running water, and cold-water swimming and a protected anchorage for small boats. Because Hurricane Island had been a flourishing quarrying town for almost a half century beginning in 1870, Willauer was immediately captivated.

By the 1970s, Outward Bound had flourishing schools all over the country, but the Hurricane Island Outward Bound School (HIOBS) provided a magnetic pull on youth because its seagoing programs along an island-studded coast, constantly subject to catastrophic weather, were the “real thing.” At its apex, more than 1,000 students per summer—from inner cities and affluent suburbs, young and old, black and white—and corporate execs went through the rigorous, sometimes terrifying rigors of sailing in a HIOBS lifeboat with 12 other novices along a beautiful but rocky coastline where you quickly learned the meaning of a lee shore.

I first met Willauer in 1975 as a graduate student in ecology. I was hired because the Nature Conservancy (TNC), an all-volunteer conservation organization at the time, had allowed Outward Bound students to camp on a dozen of their islands—sometimes with only a jug of water, a plastic tarp, a few matches, and a small tin can to cook with. This part of HIOBS self-reliance challenge was called “solo.” Although a 3-day solo created time for solemn contemplation, TNC wanted to know what effects ravenously hungry students might be having by their foraging and whether Outward Bound’s programs were harming the islands’ fragile environments.

It seemed likely to me that an earnest graduate student showing up to check on the school’s environmental practices might have caused the Hurricane Islanders to be defensive. Certainly, Willauer understood that Outward Bound’s use of over a hundred privately owned islands was an existential issue for their programs. When I arrived on one of their boat runs from Rockland, it was immediately apparent that Willauer and his staff were open to any recommendations to improve their stewardship. That was a relief and, by the way, Willauer asked if I would have time to inventory and make recommendations on their use of another 20 islands they frequently camped on.

Throughout the past six weeks of my previous island inventories on the more remote Downeast coast between Petit Manan Point and Stonington, I had scrambled ashore from the decks of lobster boats, sailboats, skiffs, canoes, and any other floating conveyance. Suddenly at Hurricane Island, Willauer offered me access to his small private Navy to take me to any island where I might ask to go. For me at age 26, it was like dying and going to heaven.

A few years later, after I graduated with a forest ecology degree, Willauer hired me to write a natural history guide to the approximately 200 islands and wilderness parcels that HIOBS had permission to use offshore of the 150-mile stretch of the Maine coast between the Kennebec River and Cutler. When that project concluded after two long seasons of field work, I was hired to help develop semester-long natural history programs. And from that work, and other island projects sprang the Island Institute, which Willauer helped me launch in 1983 and lent me five trustees to keep the new organization from capsizing.

Everything that I subsequently learned about organizational development and fundraising, I learned from watching Willauer raise money during the five years I spent with him. His philosophy might be encapsulated by this story. On his way into his HIOBS office in Rockland, Willauer would drive past a small corner grocery store on the main street of Thomaston. Every November, a hand-painted red-and-blue sign, lettered on a big role of white paper, appeared in the window that read: “If You Don’t Ask, You Will Not Get Your Turkey.” Willauer asked the store owner to make him the same sign and each November, Peter hung that sign up in his office and began calling donors.

In the early 1980s, Willauer went on to extend HIOBS’s reach to the Florida Keys and Everglades, he founded he Chesapeake Baltimore Outward Bound School in 1986, and then after leaving HIOBS founded the Thompson Island Outward Bound School in Boston harbor in 1988. All told, it is estimated that more than 59,000 students have completed Outward Bound programs in schools and programs he founded.

A small poster on the wall of his tiny office on Hurricane Island summed up Willauer’s life: “When you get to the top of the mountain, keep climbing.” Thus, after new leadership at HIOBS moved the school’s base off island to a more practical location on the St. George peninsula, Willauer returned to this newly abandoned, but beloved, island to found the Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership. He kept climbing and rebuilt the island town that disappeared twice.

Willauer certainly operated within a maritime culture that lives by the phrase, “There are old sailors and there are bold sailors, but there are no old, bold sailors.” But Willauer defied that maxim because he was exceptional.

Philip Conkling is the founder of Island Institute, along with Peter Ralston.