Though less renowned than Damariscotta’s late Barbara Cooney of Miss Rumphius fame, prolific poet and writer Elizabeth Coatsworth penned an estimated 127 total titles while living for decades in an early 19th-century house at lakefront Chimney Farm in Nobleboro. There Coatsworth and her pioneering nature writer husband Henry Beston (contemporaries of close friend Rachel Carson and Anne Morrow Lindbergh) raised two daughters, Meg and Kate (Beston) Barnes; Barnes was Maine’s first poet laureate. In 1931, Coatsworth won the Newbery Medal for The Cat Who Went to Heaven, practically her sole work still in print.

After marrying relatively late in life in 1929, Beston and Coatsworth first spent an idyllic season on an unspoiled Damariscotta “Pond” (no motorboats, fewer waterfront cottages then) living among loons on a rustic houseboat owned by local artist Jake Day. She wrote that adventure into another admired children’s book, Houseboat Summer (published by Macmillan Co. in 1942, illustrated by Marguerite Davis). Transcending genres, Coatsworth’s books ranged from poetry to memoir to a Random House four-book adult fantasy fiction series set in Maine.

She penned young adult novels about Vikings coming to North America, Native-Americans in the Southwest, and the Away Goes Sally children’s historical fiction series featuring an ox-sled-drawn log cabin in a family’s wintertime move from Massachusetts to Maine just before the War of 1812.

“There are certain figures in 20th century literature that disappear, and shouldn’t.”

—Gary Lawless

Coatsworth reviewed her own rich life in Personal Geography: Almost an Autobiography (1976).

“There are certain figures in 20th century literature that disappear, and shouldn’t,” said poet Gary Lawless, who with his wife, Beth Leonard, owns Gulf of Maine Books in Brunswick. “Kids books are timeless.”

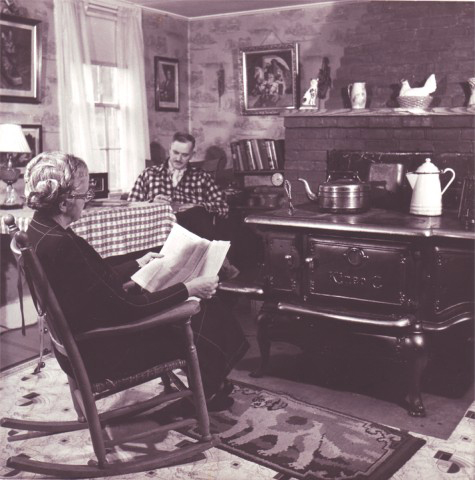

In 1986, when Coatsworth died at age 94 (Beston died in 1968), daughter Kate invited Lawless and Leonard to caretake her late parents’ 90-acre property, effective immediately, furnishings and books left on site. Once hayed with oxen who waded into the farm’s 6,000 feet of shore frontage, Coatsworth kept horses that Lawless and Leonard replaced with two cheery donkeys, named Clementine and Mavis, who inhabit the barn.

The couple inherited the farmhouse plus three acres when Kate, who phoned the couple almost daily, reciting poetry at all hours day and night, died in 2013. The rest of Chimney Farm’s almost 87 acres remain permanently protected: fields and eastern shore by Midcoast Conservancy, and woods and western shore under private protection. Coatsworth’s civilized, sociable spirit still infuses the property. Neighbors recalled her inviting the mailman in for afternoon tea, or more likely, sherry.

Upon graduation from Vassar College during the first World War, Coatsworth journeyed to Asia, including the Philippines, Japan, China, and Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. Those travels inspired her first book of poetry, nominated for both the Yale Younger Poets and the Borzoi prizes, Lawless recounted. (As a teenager prodigy, protégé daughter Kate had her first poem published in the New Yorker.)

Coatsworth later traversed Morocco and Tunisia on camelback and Guatemala on a donkey. Then she took her young daughters throughout Europe.

“They loved to travel, and when they did, she’d gather material for a kid’s book,” Lawless said.

Now, with the recent release of the novels of Mount Desert Island’s Ruth Moore, Islandport Press and others told Lawless of their interest in reintroducing readers to Coatsworth. Someone, even a high school student, should also write a proper Elizabeth Coatsworth biography, Lawless urges. Husband Henry Beston has one, but not her.

As an elderly Coatsworth grew ill, daughter Kate returned to Maine. Before her mother’s death, Kate asked Lawless to republish her mother’s prize-winning chapbook of poetry, Fox Prints.

“So her first book was her very last, too,” he jokes. And at the end of Coatsworth’s funeral in the pasture next to the farmhouse, Kate asked Lawless to read two of her poems “so that she had the last word.”

“I have always hated to wait for things,” Lawless read from Personal Geography. “I think I will go to meet whatever it is.”

Visit the gravesites of Coatsworth, Beston, and Barnes in the family cemetery at 617 East Neck Rd., Nobleboro

The University of New England’s Maine Women Writers Collection maintains Coatsworth’s (and Kate Barnes’) voluminous correspondence, photographs, and books. And the Lincoln County Historical Association (with support from the Lincoln County News) will celebrate the county’s many historic and current women writers through exhibits and lectures starting in June, throughout the summer.

Reporting here based on an interview with Gary Lawless.