Sometime back in January, Maine Audubon announced that the renowned entomologist, ultra-marathoner, University of Vermont emeritus biology professor and acclaimed author Bernd Heinrich would be speaking about “the nexus of art and science” at its Field Pond Center in Holden. A few weeks later, a follow-up email arrived: due to intense interest in the talk, the venue had been changed to the East Orrington Congregational Church.

By the time Eric Topper, Maine Audubon’s director of education, stepped to the front of the church to introduce Heinrich, the pews had filled with fans. Heinrich, now 76, displayed the classic twinkle in the eye, here related to the special pleasure he takes in telling stories about natural history. Whether describing his interactions with various birds or recounting a bit of botanical legerdemain, he captivates.

After claiming with a smile that he wasn’t sure what “the nexus” of art and science meant, Heinrich proceeded to provide an outline of the intersection of these two disciplines in his own development as an observer of the natural world. As he stated in the afterword to Nature and Culture: The Paintings of Joel Babb (2013), “Art and science come from the same wellspring. Neither originated from the utilitarian and both spring from the aesthetic.”

Heinrich built his talk around his autobiography, beginning with his father, Gerd Heinrich (1896-1984), a renowned Polish-born zoologist who specialized in ichneumon wasps and who sought out rare birds and other creatures in remote outposts before, during and after the two world wars. As told in his son’s extraordinary book The Snoring Bird (2007), Heinrich senior’s life story features its share of Indiana Jones moments—not to mention the swamp scenes in The African Queen and the behind-enemy-lines parts of Jerzy Kosiński’s The Painted Bird.

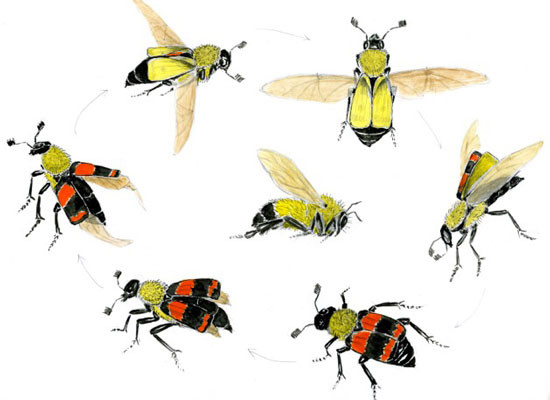

Wing-cover twist of an N. tomentosus beetle in flight with (at center) one of several bumblebees it mimicks, pencil and watercolor (from Life Everlasting: The Animal Way of Death, 2012).

If young Bernd was sometimes a reluctant recruit on his father’s collecting expeditions, he came to love the study of nature. Indeed, the first image he shared with his East Orrington audience was a handsome rendering of a stag beetle that he drew as a nine-year-old, and which served as a birthday card for “Papa.”

The family emigrated from Germany to America in 1951, eventually ending up in Wilton, here in Maine. Heinrich and his younger sister Marianne were eventually placed at the Good Will Home, a “school-home-farm” for disadvantaged kids, while their parents went off on collecting expeditions. Heinrich recounted how he kept his prize collection of caterpillars in the basement of the school’s natural history museum. (The L.C. Bates Museum remains one of the most engaging repositories of natural history specimens in New England. A visit these days will allow you to view the newly restored marlin caught by Ernest Hemingway.)

In keeping with the title of his talk, Heinrich shared original studies of flora and fauna, done in pencil and watercolor, recruiting Topper to carry them down the aisles. One drawing showed a burying beetle mimicking a bumblebee in flight, a remarkable feat—and a stunning depiction of it, precise and dynamic. The drawing is reproduced in his Life Everlasting: The Animal Way of Death (2012).

Heinrich framed each natural history story around a conundrum. One of the best of the evening involved the yellow flag iris. The naturalist noticed that this iris could be readily observed as a bud or a flower, but that there appeared to be no transition between these two phases—no unfolding. How could that be? By attentive observation, he discovered the answer: having built up pressure, the buds “explode” into flower.

In the Q & A at the end, one audience member asked if Heinrich was interested, like his father, in pursuing the rarest of creatures, such as the snoring bird (aka the “holy rail”). The trim man with spectacles, who is perhaps best known for his work with ravens (which he studies near his home in western Maine), replied that he preferred to study known species in order to find out something new about them—observe them as no one had observed them before. Throughout the evening we were reminded of the success of those endeavors, and that Heinrich is a master at revealing the wonders of the intimate and sometimes confounding world of nature.

Heinrich will be the guest naturalist at Natural History Week on Star Island, June 18-25: www.nhcstar.org. His latest book, One Wild Bird at a Time: Portraits of Individual Lives, is due out this spring.

Heinrich won the John Burroughs Association award for outstanding nature essay of 2016, “Chickadees in Winter,” published in Natural History Magazine. (At the same ceremony, Kim Ridley of Brooklin received the Riverby Award for exceptional nature writing for young readers for The Secret Bay.)