High energy costs are a persistent issue across island and remote coastal communities, and addressing them presents multiple challenges. Finding funding and professionals willing to deliver energy services in these communities can be difficult. A crucial first step is bringing the community together in order to raise awareness of opportunities and increase demand for energy services. Islesboro is taking a unique and effective approach, laying a foundation of knowledge and enthusiasm using a community-based model focused on education and empowerment of residents of all ages. This particular example highlights how the strategy has succeeded with students from the Islesboro Central School, empowering a group of high schoolers to lead an energy saving project from start to finish, and beyond.

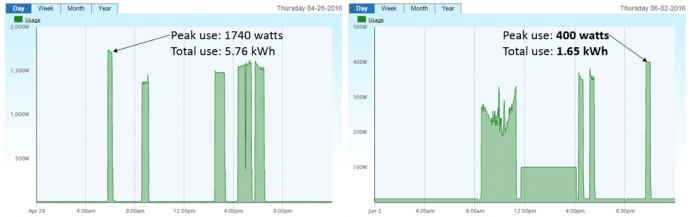

During the spring of 2016, students at the Islesboro Central School analyzed the energy use within their classroom using a tool called the eMonitor, which measures electricity use minute by minute and circuit by circuit throughout the building. Based on the results, the students estimated energy and dollar savings from updating the lighting, and then retrofitted the room with LED lighting using a grant from the Island Institute/Islesboro Energy Team. They were then able to compare their estimates of savings using real time numbers from the eMonitor. Read a blog post about the project here.

HOW IT WORKS

This project was effective in creating energy savings beyond one classroom. Students wrapped up their project in spring 2016 by making a case to the school board that the entire lighting system should be retrofitted with efficient LEDs. Community members tend to listen when students create well-rounded, specific arguments advocating for change. The presentation was well received by the board, who requested that the students return the following year with a more complete proposal.

IMPLEMENTATION STEPS

- Meet with students, pitch project idea and assemble an interested group – Who is doing this?

- Inventory lighting in one classroom – Is room too bright/too dim?

- Calculate savings based on estimated power consumption of LED lights

- Purchase, install LED lights

- Collect data on new lights and update savings in order to compare with pre-installation estimates

- Present results to school/community building administration and highlight potential savings for the rest of the building

- Share results – Make a presentation to the broader community and help other buildings implement similar projects

KEY FACTORS

- Student and school interest in reducing resource use

- Strong mentorship from within the school, community, and supporting organizations (Island Institute staff in this case)

- Grant funds to spark the project and incentivize school/municipal spending

- Providing the project team with a chance to “show off” to the community with a presentation

CHALLENGES

- Limited class time slowed progress and students had no capacity to meet after class. Having mentors who could guide the students through the project was crucial for making good use of this time.

- Access to an eMonitor with a record of past electricity use in the space is a major benefit – but most schools don’t have eMonitors or other sophisticated energy monitoring tools. In the absence of such a tool, estimations will need to be done by hand without actual measurements.

- The goal was to advocate that the school use part of its budget for continuing the lighting retrofit to the rest of the building. This can be difficult to accomplish, as schools and towns have longer term budgeting cycles and many are facing budget constraints making it difficult to approve funding for such projects on short notice. One option that could work well for school’s budgets would be to slowly switch out the lighting section by section over the next few years.

Q & A WITH EMILY LAU, PROJECT TEAM MEMBER

Tell me a little about yourself and your project.

I live on Islesboro, Maine, and I go to Islesboro Central School. We started an energy team last year after being inspired by the Island Institute to put in LED lightbulbs into the school. We’ve been working on getting the entire school switched to LED lightbulbs since last May

How did this project get started? Who identified the need?

The project was started by the Island Institute by providing us with support funds and training and really getting our interest sparked.

What were some of the hardest parts?

One of the hardest parts was collecting data efficiently. Our team only met once a week for 45 minutes, and collecting consistent and useful data was sometimes difficult. It was also a little difficult to figure out how to use the tools for data collection, but once we got that down, it was fine.

What would make a lighting project like this easier next time?

The Island Institute was really helpful in getting us lightbulbs, which made it easier. If we had learned how to use the energy-testing tools and what they meant beforehand it may have been slightly more efficient, but it was a good learning process for us to go through, so that wouldn’t really be necessary.

What is something you wish you had known before starting, or would have done differently?

If I could have somehow organized the eMonitor data collector before we started actually collecting data (separating one room from the others, and specifically its light usage), it would have been easier to show how much more efficient LED lightbulbs are.

What resources or similar projects have you learned from?

Since last year, we’ve definitely progressed in understanding the basics of energy-talk — what kilowatt-hours are, what lux are, how to use the eMonitor, etc. — and we’re learning even more from the current project of replacing all the lightbulbs in the school.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to complete a similar project?

I would suggest making sure everything is very organized. We didn’t have any trouble replacing the bulbs themselves, because we had specific bulbs that fit into the fixtures that already existed. Besides that, I’d say just go headlong into it, because it will all work out!

What else do you want people to know?

The project was really awesome, and we’re really grateful to the Island Institute for helping us get started on a path to energy efficiency, because it’s very important to this world.

OUTCOMES/RESULTS

The outcomes of this project are numerous. In addition to saving energy in their classroom, the students felt empowered and received positive recognition from within the school and their community for moving this project forward.

Originally Published March 2016