On a warm July afternoon, Steve Smith sat outside a fish house in Otter Creek on Mount Desert Island, telling stories. There was the time it was “Blowin’ like a bastard from the north,” and his skiff capsized. A pair of park visitors heard Smith calling for help, hopped in a nearby rowboat and rescued him.

While Smith regaled me with this tale, a large gull landed gracelessly on a nearby piling, evidence that there was once a functioning dock here, now buried by debris from the 2024 winter storms.

“Jonathan!” Steve interrupted himself, calling to the gull. “No food today! Sorry,” and threw up his hands to reveal empty palms. The bird turned mechanically towards us and gave no indication it would accept no for an answer.

Smith and his friends built this fish house in the 1970s. It’s off the beaten path, but its setting—deep in Acadia National Park—means it represents one of the last vestiges of Otter Creek’s working waterfront heritage which, Smith says, has been stifled by the park’s presence.

In the summer of 2024, Acadia National Park welcomed an average of about 20,000 tourists each day, many of whom drove along Route 3, a major artery that connects Bar Harbor, Seal Harbor, and Somes Sound. Otter Creek might be overlooked by those driving to other destinations. Confined within the national park borders, to the undiscerning eye, the village is nothing more than a crossroad.

A lifetime before Smith was born, we would have beheld a waterfront village bustling with commerce here in Otter Creek. In the late 1800s, decades before the park was established, a score of small fishing boats would have been moored here. Down by the shore, men would have been baiting trawl lines with shucked mussels in their fish houses.

Quarry workers loaded schooners full of Otter Creek’s signature pink granite for construction projects across the eastern U.S. Farmland rolled out to the sea, providing sustenance to the dozens of Otter Creek households.

Today, the surrounding land is owned and managed by the national park. Spruce and pine trees now block the view to the water. This coastal village feels landlocked.

“They’ve been picking away at us,” Smith says, “stealing one piece after another for over 100 years. They’ve almost taken our waterfront, but they won’t as long as I’m alive.”

Otter Creek has changed substantially, but in the 2012 report “The Waterfront of Otter Creek: A Community History,” anthropologist Douglas Deur remarks on the village’s ability to withstand decades of pressure:

“The little village has exhibited remarkable stability despite shifting economic fortunes, changing ownership of its waterfront, and the social transformation of the larger island community of which it is a part. Families that arrived in this little cove some 180 years ago are still here; they continue to thrive, and it seems likely that they will be there for many more years to come… There is a great pride in the shared and individual histories associated with this place.”

Otter Creek, like other harbors around Mount Desert Island, was of cultural importance to its inhabitants for thousands of years, first as seasonal access to fishing grounds for Indigenous tribes. Permanent white settlements began in Otter Creek in the 1830s with households with family names that remain in the area today—Walls, Davis, and Smith.

For the first few generations, Otter Creek was a thriving, though insular community of subsistence fishermen and farmers. Men fished for cod, lobster, and haddock, and returned home to till their fields. Land ownership wasn’t a concern at the time, and access to the water was granted informally. If a neighbor owned a plot of land with waterfront access, they gave permission to the village fishermen to use the shore for their fish houses and boat slips. Throughout its history—and in later years to the community’s disadvantage—waterfront access in Otter Creek was largely granted by handshake deals.

The turning point for Otter Creek came in the early 1900s, around the time one of the richest men in the world, John D. Rockefeller Jr., of the family that founded Standard Oil, was charting a future for the National Park System with Mount Desert Island in mind. Rockefeller collaborated with Charles W. Eliot, then-president of Harvard University, and George B. Dorr, known as the father of Acadia National Park, to change Mount Desert Island forever.

From the hindsight perspective of Otter Creek residents like Smith, these men’s vision threatened the fishing community’s survival. Through donations from wealthy landowners and by transacting with locals under the title of the proxy company, “Otter Creek Realty,” their goal was to acquire the entire Otter Creek waterfront for the new national park.

The dream that Rockefeller brought to life included a stone causeway that bisects Otter Creek. The inner harbor was supposed to become a swimming hole for park visitors and MDI locals, intended by the elites to draw the masses away from the Seal Harbor beaches. That swimming hole never came to be and instead manifested as a mud flat.

Smith refers to the causeway as the “Wall of Death,” because it restricts adequate tidal flushing and “killed the inner harbor.” He describes the inner harbor as a cesspool for invasive green crabs and claims it is barely usable for working waterfront purposes.

Born in 1946, Smith witnessed the collapse of the Otter Creek fishing fleet during his childhood. As a teenager, Smith remembers Harold Walls, the last full time commercial fisherman on Otter Creek, hanging up his nets, at least in part because of waterfront access struggles. He became a caretaker for private island properties. Park officials planned to demolish his fish house, but according to some accounts, Walls dismantled the structure himself before the park could.

Smith has spent his life fighting to conserve the waterfront identity of Otter Creek. If Smith is the biblical David, then the park service is Goliath.

Smith recounts one of many showdowns from the 1970s. A fish house on the harbor had gradually become dilapidated as tourists stripped its shingles for souvenirs. Smith set out to repair this symbol of his heritage, but while doing maintenance, park rangers told him he did not have permission to alter the structure and instructed him to stop. The conflict escalated, and Smith refused to leave the park headquarters until he knew exactly why he wasn’t allowed to repair the structure.

“I finally got an answer out of him,” Smith recounts. “He popped up out of his chair like a sculpin out of 40 fathoms of water, and he said to me, ‘Eventually, we plan on phasing you people out completely.’”

Smith researched the transaction of each waterfront parcel on Otter Creek, poring over decades-old deeds and records that dated back to the Rockefeller acquisitions through the 1930s. He identified one fraction of an acre on Otter Creek that was overlooked and technically never granted to the park. He rounded up his friends and began to build a fish house there.

National park staff noticed and again admonished Smith mid-construction. Standing on the roof of the unfinished fish house, Smith said he had documentation to prove Otter Creek fishermen had the rights to this parcel of land. Years of legal battles followed, during which Smith commuted to Washington D.C. to advocate for the fish house.

The park also encroached upon another critical piece of waterfront, the Otter Creek boat launch, close to the mouth of the harbor, which had been used by fishermen for over a hundred years. In 1983, the park blocked access with boulders. But in part due to his advocacy, the barriers were ordered to be removed from the boat launch road, and Smith finally obtained a deed for his 484-square-foot parcel on which the last Otter Creek fish house stands.

The structure burned, with arson suspected, but Smith and others rebuilt it. The fish house remains on the waterfront parcel, and before the 2024 winter storms, Smith used the nearby dock for his parttime lobstering work. The deed to the fish house is now held by the Aid Society of Otter Creek, ensuring it will remain accessible.

“You don’t get pearls out of oysters without irritants,” says Durlin Lunt referring to his old friend Steve Smith’s tactics. Having served as town manager for 15 years for the town of Mount Desert, Lunt is another leader in Otter Creek’s fight for its waterfront heritage. While Smith uses civil disobedience and plays hardball, Lunt works within the confines of town politics.

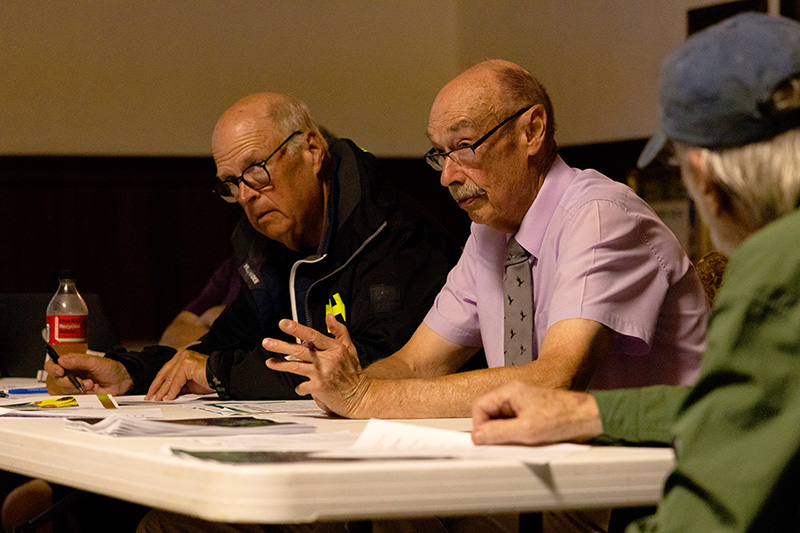

Lunt was the featured speaker at a July 2024 Aid Society of Otter Creek meeting where he outlined his strategy to reconnect Otter Creek to its waterfront heritage. The village straddles the border between Mount Desert and Bar Harbor, so the Aid Society of Otter Creek acts as a sort-of governing body, and its meetings serve as a venue for civic engagement.

As emphasized in Lunt’s presentation, the current battleground between the village and the national park is a 3,000-square-foot parcel of land—about the size of a tennis court—that borders the boat launch. The launch is seldom used because the causeway chokes the tidal flow and the ramp only touches water at peak high tide.

“We shouldn’t have to go to Washington D.C. every time we want to move a shovel of earth,” Lunt said at the aid society meeting, eliciting nods and subtle applause. He believes restoring the viability of the boat launch will benefit the park, its visitors, and Otter Creek residents. His ideal scenario would include leasing the land from the national park. But when dealing with a federal entity, striking a deal is never simple.

Rebecca Cole-Will, interdisciplinary chief of resource management at Acadia National Park, sat in the front row at the meeting in Otter Creek Hall. She described the event as more tense than usual, fielding pointed questions about ongoing work on the causeway. Otter Creek villagers demanded to know why over $2.5 million was allocated for maintenance on the “Wall of Death.” It appeared that most attendees at the meeting would have rather seen the causeway removed, not repaired. Cole-Will said that the causeway construction had long been planned and was necessary rehabilitation exacerbated by the 2024 winter storms.

Representing the organization that many Otter Creek villagers view as an adversary can be a challenge, but Cole-Will’s specialty is place-based sensitivities.

“National parks are more than access to nature,” Cole-Will says. “They’re places of intense history. They’re places where people lived and endured—battlefields where blood was shed. It’s important for us to recognize that this isn’t just a beautiful natural space. This is homeland.”

Much of her work has been with Indigenous tribes, learning about traditional land uses. She works with “people who have been removed, who’ve been erased, who have deep enduring ties to place that have not always been recognized or afforded.” Those lessons have been applied to her work with Otter Creek. But decisions about land use are mostly outside of her control.

“It takes an act of Congress,” she says, referring to altering the borders of Acadia National Park.

In 1986, then-Sen. George Mitchell ushered his Acadia boundary legislation through Congress, which prohibits the park from acquiring land outside its boundaries and bars it from parting with any land except for occasional leases to municipalities for infrastructure like wastewater treatment sites and very rare land swap deals.

Any land use deal would need support from the Department of the Interior. Granting land back to Otter Creek for a landing could lead to other towns and tribes asking for land back.

“They’re afraid of opening up a can of worms that they would rather keep sealed,” Lunt says, “and it really is too bad because that makes it devilishly difficult for the park and the surrounding communities to be good neighbors.”

Cole-Will believes “The best solution going forward is that we continue working together and make sure the history of Otter Creek is told and documented.”

As for the causeway—the “Wall of Death”—addressing the tidal flow of the inner harbor is an ongoing discussion. The park and Otter Creek would both benefit from the improved health of the inner harbor.

Cole-Will says the park has commissioned biological surveys in the inner harbor and is open to solutions that will restore habitat and use. But the park has a responsibility to manage the causeway as a historic resource.

Smith believes the causeway’s protection represents a misplacement of priorities. “It should be the park’s responsibility to manage the inner harbor as an ecological resource. We once had a pristine estuary there. Now it’s dead.”

Lunt, slated to retire in August, is confident the fight to preserve Otter Creek’s waterfront heritage will be fought for years to come. The Mount Desert Selectboard passed a resolution now part of the town’s comprehensive plan, designed to be a roadmap for the next decade. The resolution prioritizes “tidal flushing of the inner harbor [which is] essential to the ecological health and well-being of the harbor” and states “it is essential to re-establish access to and egress from the boat ramp in an efficient manner.”

Because of the work of advocates like Smith and Lunt, the next generation of Otter Creek leaders has their work laid out for them. Lunt may be stepping down from his role as town manager, but he envisions a bright future for Otter Creek.

“I have told Steve many times, ‘You’re Moses. You’re going to see the promised land, but you’re never going to get there.’ Neither he nor I will be alive when Otter Creek reclaims its waterfront identity, but the next generation will be.”

Jack Sullivan is a multimedia storyteller with Island Institute.