In early April, a small but powerful group of community leaders, educators, and volunteers from across Maine’s fishing communities gathered in Stonington for a train-the-trainer workshop co-hosted by the Island Institute, Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, and the Department of Marine Resources (DMR). The objective: to prepare trusted local volunteers to support harvesters as they navigate new digital landings reporting requirements in the lobster industry.

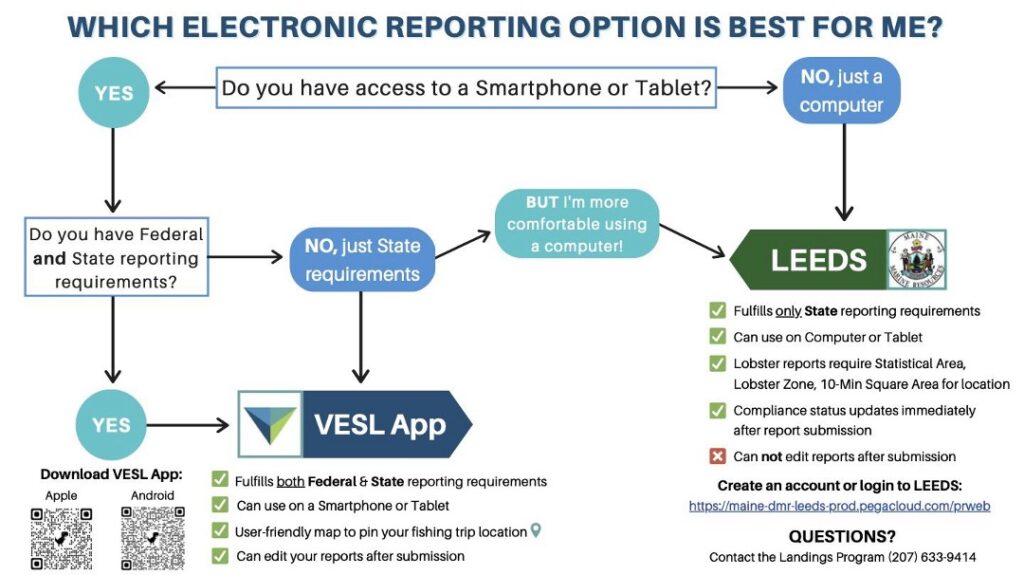

The shift from paper logbooks to online reporting platforms like VESL and LEEDS has introduced a steep learning curve—especially for older harvesters who may not own a smartphone, use email, or feel comfortable navigating online portals. With federal exemptions ending and compliance expectations increasing, the stakes have never been higher. A missing report can prevent license renewal.

“Entering your data is how you make your voice heard,” said Beals Islander Amanda Smith of Sunrise County Economic Council. “If we have the data, we can tell our own story. If [the government] is the only one with the data, they can tell whatever story they want about you.”

That comment became a touchstone for the day, grounding the conversation in a forward-facing vision: digital reporting isn’t just about compliance; it’s about local empowerment, business resilience, and community-led storytelling.

Barriers and Trust

Throughout the training, participants shared candid insights from their communities. Several explained that it’s often spouses or other family members doing the reporting, while harvesters themselves struggle with digital systems that feel foreign to commercial lobstering, one of the world’s only owner-operator fisheries, stewarded by generations of fishing families since the 19th century.

A younger fisherman from Frenchboro summed up the frustration: “The ocean used to be my office. I chose this because I didn’t want to work at a computer. It takes the joy out of the job I love.” That feeling – that something essential is being lost in translation – came up again and again.

Angela Cox, who helps her father in Dennysville manage his reports, spoke about the informal workarounds she’s developed, like printing out emails or creating simplified paper forms to gather information from him.

This kind of unpaid, often invisible support is happening up and down the coast. And while DMR has worked hard to provide technical assistance and outreach, trust and access remain major challenges. As one compassionate DMR staff member noted, “People aren’t coming to me when they’re in a good place.”

Building Local Capacity

That’s why this training focused not only on demos of the reporting platforms themselves, but also on how to build local capacity in a sustainable way that meets the unique needs of each community. Participants explored how Adult Education centers and informal social networks can become essential lifelines for fishermen and their families.

Morgan Whitham of Deer Isle Adult and Community Education emphasized that the mindset shift is just as important as the software skills: “If you’re going to have a business in this day and age, digital reporting is part of doing business.”

Ideas for future support included:

- Local “catch-up parties” with snacks and childcare to help harvesters get caught up before license renewals.

- Training librarians and community health workers to be navigators for reporting systems.

- Amplifying DMR’s quarterly updates on common reporting hiccups.

- Offering grants or business resilience funds to build more formal programs supporting family members doing digital compliance work.

From Compliance to Storytelling

Participants left the day energized by the shared commitment to community problem-solving, and more aware of the barrier posed by digital systems not built for the working rhythms of a lobster boat.

Still, the central message came through loud and clear: digital data is not just a burden – it’s a tool. And when held and understood locally, it becomes a form of power.

As Amanda reminded the group, “If you don’t have the data, you can’t start pinpointing where it doesn’t make sense.” Whether it’s advocating against misguided policy or pushing back on mischaracterizations of a community’s economy, the data – when owned and interpreted by harvesters themselves – can defend livelihoods and shape futures.

Island Institute will continue to support these cross-sector partnerships and locally rooted training efforts as part of our Future of Fishing initiative. Because in the end, building digital resilience in Maine’s fishing communities isn’t just about technology—it’s about trust, voice, and telling our own story.