Like most kids growing up on the Penobscot Reservation at Indian Island, just north of Bangor, Donna Loring traveled across the river to Old Town to attend high school. She didn’t like it.

In those days, the Old Town High School mascot was an Indian. “I would be made fun of and discriminated against,” recalls Loring, now a Penobscot Elder. She eventually secured a scholarship to the now-closed Glen Cove Christian Academy in Rockport. In neither school did her education include one word about the Wabanaki—the People of the Dawn—who have lived for more than 12,000 years in what is today called Maine.

“What were we taught about Wabanaki history and culture? Not a thing,” she says.

Some 40 years later, Loring decided to do something about that omission. While serving as Penobscot tribal representative in the legislature, she sponsored a bill that requires Native American history and culture to be taught in all Maine schools.

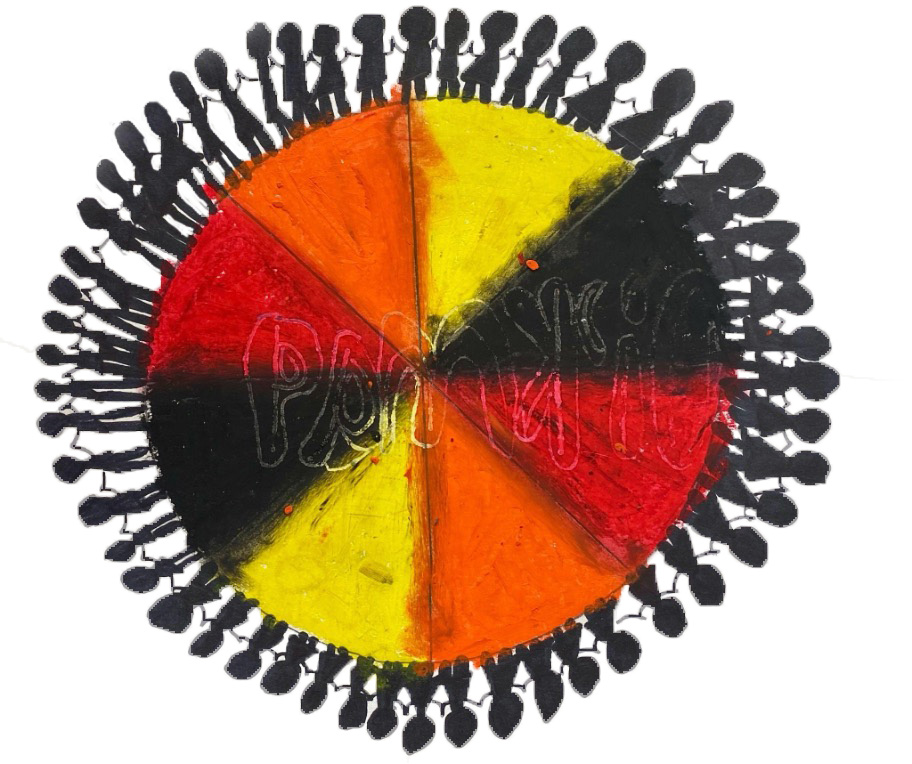

“For a long time, the average person in the state didn’t know there were four Maine tribes—and they couldn’t name them,” Loring says. (The Wabanaki tribes living in Maine today are the Penobscot Nation, the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Motahkomikuk and Sipayik, the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, and the Mi’kmaq Nation.)

The Wabanaki Studies law was the first of its kind in the nation when it was enacted in 2001. But in the two and a half decades since, it has not lived up to its potential. Discussions of Indigenous people are still largely absent from the classroom. Lessons that do mention Native communities tend to reinforce negative and inaccurate stereotypes, or to imply that the Wabanaki are no longer here. Now, that’s beginning to change.

The biggest impediment to widespread implementation of the law: a lack of resources. The law established a 15-member commission (eight chosen by tribal governments) to begin to shape Wabanaki Studies curricular content and help educators satisfy the new mandate. The law did not, however, include financial support to help schools implement the law. The commission was sun-setted after two years.

A comprehensive assessment of the Wabanaki Studies Law in 2022 concluded that its requirements are “not meaningfully enforced across the state, school districts have failed to consistently and appropriately include Wabanaki Studies in their curriculum, and teacher training and professional development remain insufficient to equip educators to teach Wabanaki Studies.”

The report, prepared by the Wabanaki Alliance, ACLU of Maine, the Abbe Museum, and the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission, offered recommendations for fulfilling the promise of the law and was a catalyst for renewed attention and action.

“We didn’t want it to be a gotcha report, but a snapshot in time and a way to look at how we can help schools to do better,” says Maulian Bryant, who last year stepped down as the Penobscot Nation’s Tribal Ambassador to become executive director of the Wabanaki Alliance, where she advocates for tribal interests in Augusta. “The good news is that during the past four to five years, some good work has been done.”

One critique has been that the state Department of Education has not done enough to support and enforce the legislation. But Pender Makin, DOE commissioner, says the department is committed to doing better.

“For thousands of years, the Wabanaki Nations have thrived in Maine, with distinct languages and governmental structures,” Makin said in response to an email inquiry. “The Maine DOE believes it is essential for all students to learn about the rich cultures, histories, and traditions of the Wabanaki Nations and their enduring presence in our state.”

In 2022, DOE asked Penobscot citizen and Old Town Elementary School teacher Brianne Lolar to leave her classroom for one year to help create seven Wabanaki Studies modules. The role turned into a full-time position as the department’s first Wabanaki Studies specialist. DOE also entered contracts with content advisors from all the Wabanaki nations.

Although much of Lolar’s early work coincided with the pandemic when classroom-based instruction was suspended, the learning modules were the launching pad for many additional resources, including teacher training materials, professional development workshops, and interdisciplinary educator guides geared to each grade level.

The goal, Lolar says, has been “to take away all possible barriers to integrating Wabanaki studies into the schools.”

Veteran social studies teacher Emily Albee partnered with Lolar to introduce Wabanaki content to her students at Hampden Academy, a comprehensive public high school with an enrollment of 740. Albee piloted curriculum, vetted units, and created new content, including a course she co-teaches with her school’s assistant principal Ryan Crane.

“We bring in guests from the Penobscot community,” Albee says. “We help kids connect the dots to understand that their high school is located in the homeland of the Penobscot Nation.”

In the fall, she organized a school-wide assembly with Wabanaki community members that featured drumming, dancing, and music, and introduced project-based learning, such as a collaboration with Chris Sockalexis, tribal historic preservation officer for the Penobscot Nation. Sockalexis arranged for the school to borrow artifacts. Albee’s students interviewed Native experts, researched the artifacts, and curated an exhibit in one of the school’s unused trophy cases.

As a child growing up in Milford, Jenny Becker was told, “You don’t go to Indian Island—they’ll shoot at you with arrows.” Years later, when she married a Penobscot citizen, the couple lived there. Today, the Brewer Community School teacher works to instill in her second-grade students a more accurate portrayal of their Indigenous neighbors.

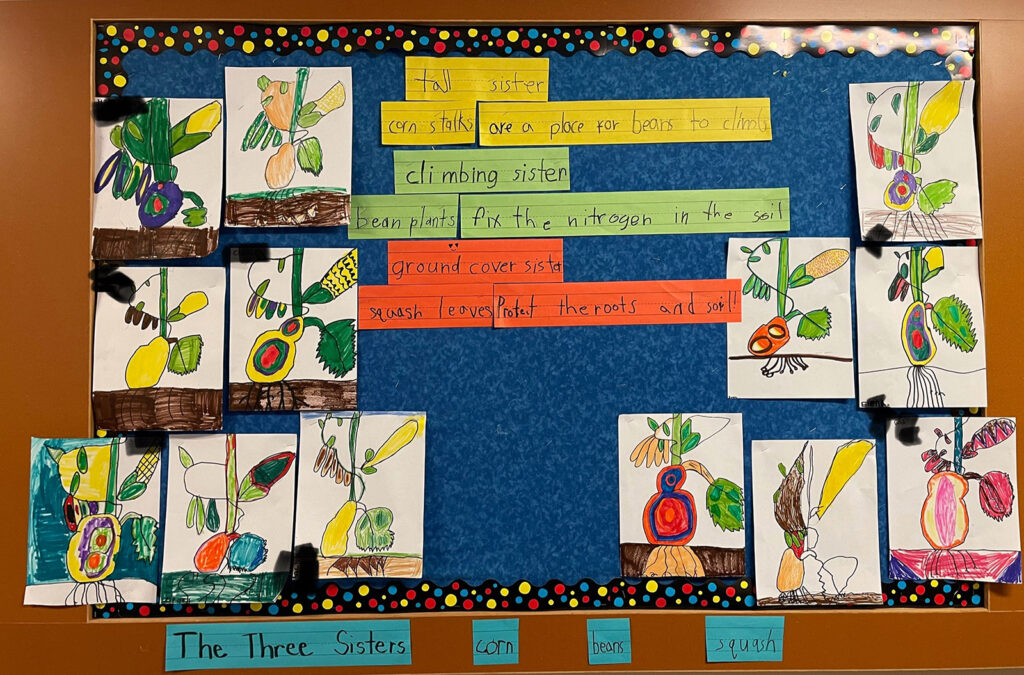

Becker integrates Wabanaki studies into all her units over the course of the year. She teaches about the three sisters (beans, squash, and corn) and why those crops were planted together; her students learn about the Wabanaki oral tradition of Gluskope, the benevolent warrior against evil and possessor of magical powers; and a science unit on matter builds on the Wabanaki practice of using ash tree strips to make baskets.

Becker has also taken advantage of grade-appropriate thematic kits containing primary sources, discussion guides, and recommended classroom activities available to educators from the University of Maine’s Hudson Museum.

“The content is very powerful for an educator,” Becker says. “Second graders are especially excited to learn new languages and about different cultures.” She adds: “This is the first year I’ve used the term ‘colonizers’ with second graders. They understand. We talk about learning from mistakes in history.”

The most comprehensive and, by many measures, most successful effort to implement the Wabanaki Studies law has been in the Portland Public Schools. Portland’s pre-K-12 Wabanaki Studies curriculum is the result of a seven-year collaborative process involving teachers, parents, community partners, and more than 70 Indigenous advisors and content contributors from all Wabanaki tribes.

The effort was spearheaded by Fiona Hopper, who credits administrative support at the district level and a methodical commitment to cross-cultural relationship building with Wabanaki knowledge holders.

One of Hopper’s close collaborators, Penobscot Citizen Darren Ranco, professor of anthropology and chair of Native American Programs at the University of Maine, describes Portland’s approach as “comprehensive, mission-driven, and done in collaboration with Native partners. That is the magic sauce here.”

The 6,500-student Portland system is not only Maine’s largest school district, but also the most diverse. About one-third of the students come from homes where languages other than English are spoken—a total of 53 languages. Approximately 48 percent of the district’s students are white, and 52 percent are students of color.

“What has struck me is the way in which students who have direct connections and experience with colonization relate to learning about Wabanaki studies,” Hopper says. “It is affirming for students to know that English is not the original language of this place and that there are people like them living in Maine who share a similar history and story. I’ve watched that ‘A-ha!’ moment happen with students from a myriad of different backgrounds.”

Hopper and her colleagues say the Portland curriculum is “very replicable” and they hope to share it broadly with other districts across the state.

“There is absolutely a desire and willingness to share it beyond Portland. We’re trying to figure out how do we share it in a responsible way. Throwing it up on a website would mean that people wouldn’t be replicating the Portland process that included very strategic professional development in order to understand and use it well.”

Lolar from the Department of Education says she’s seen “kids starting to look at things differently after being exposed to Wabanaki studies—and not just kids, adults too. It’s a new way to look at things, it’s a world view.”

“We recognize that not all of our history in what is now Maine has been taught,” says UMaine Professor Ranco. “We want to create a deeper understanding across Native and non-Native communities. The more non-Native people know about Native people, the more we can get along and shape a collective future together.”

Paul Karoff is a Camden-based freelance writer. Until 2024, he was an associate dean at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and previously held senior communications and public affairs positions at nonprofit and higher education organizations and at a Fortune 100 Company.